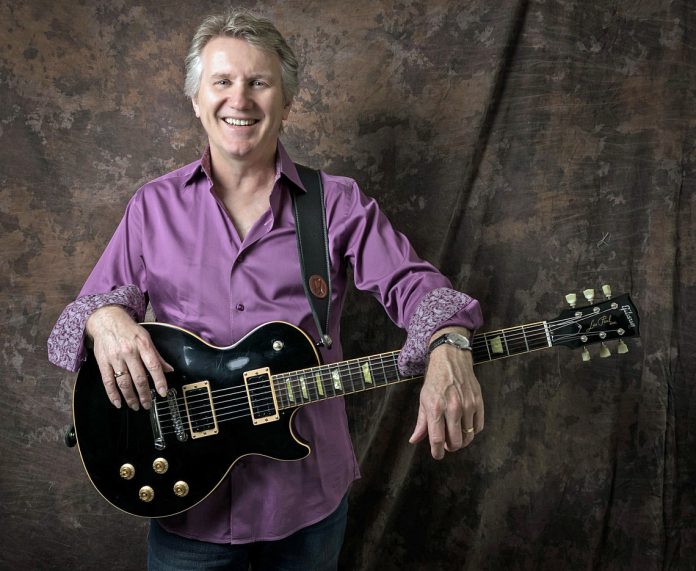

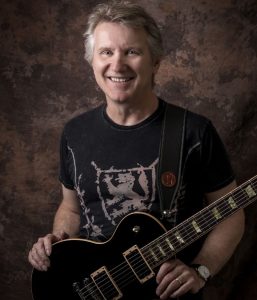

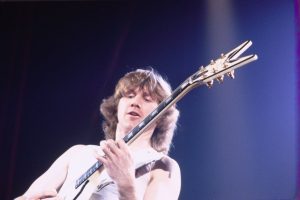

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: October 2021. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary musician and a highly intelligent person: Rik Emmett. He is best known as the vocalist, guitarist and songwriter of Triumph, a very successful Canadian hard rock band. After his departure from Triumph in 1988, he embarked on an acclaimed solo career. He just released “Reinvention: Poems”, a largely autobiographical poetry book, published by ECW Press. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

Why did you decide to write a poetry book “Reinvention” and not a usual autobiography?

Well, I will eventually write an autobiography, a memoir. That will be the next book that I write, but as I retired from travelling on the road and playing concerts, I didn’t stop being creative. I mean, I’ve always written some poetry every now and then but I had never decided to buckle down and write a whole book thinking I might try to get it published. But it was just my creativity led me towards researching about poetry and reading books about poetry. I’ve read some poets that I really enjoyed and admired and that led me to the idea of writing poetry. A lot of the poetry is largely autobiographical, not all of it, but a great deal of it and in a way I liked the fact that I had a kind of a creative license to use poetry to be autobiographical. So yeah, those are the main reasons.

Well, I will eventually write an autobiography, a memoir. That will be the next book that I write, but as I retired from travelling on the road and playing concerts, I didn’t stop being creative. I mean, I’ve always written some poetry every now and then but I had never decided to buckle down and write a whole book thinking I might try to get it published. But it was just my creativity led me towards researching about poetry and reading books about poetry. I’ve read some poets that I really enjoyed and admired and that led me to the idea of writing poetry. A lot of the poetry is largely autobiographical, not all of it, but a great deal of it and in a way I liked the fact that I had a kind of a creative license to use poetry to be autobiographical. So yeah, those are the main reasons.

Is it intriguing for you the fact that poems are usually more open to interpretations than song lyrics?

Yes, that is very true. When you write song lyrics, from an architectural point of view that form is very demanding: rhyme schemes and phrasing. So, it was nice to be able to write without necessarily having to show off those architectural, structural problems of lyric writing. But any kind of creative writing presents its own set of problems. You are always dealing with some issues of form and structure and I believe in it in a very strong way, but writing poetry does give you more freedom. That’s definitely something that I enjoyed.

Is “Reinvention” a Rik Emmett’s journey through emotions?

I would say the writing of a book is a journey of a lot of things and I think the things that made me write poetry are not different than other poets in the past throughout history. I think when we get older and we face our own mortality, that’s one of things that makes a writer write. A friend of mine, a poet named Adam Sol said: “The world is a broken place and people go to their creativity in order to try and figure out how they feel about this brokenness”. I think it’s a thing about our humanity, really, in the end. I mean, one of the reasons that I wrote a lot of the poems in “Reinvention” is because my own personal, internal pendulum swings from one side there are a lot people and I want to offer people something creative, I want to offer them art, which is a beautiful thing and then my pendulum swings the other way and I find that people are so stupid, so ignorant and so cruel towards each other and that drives me crazy. So, the writing of poetry sort of helps me deal with my pendulum swinging from side to side: From my misanthropy on one side to my love of humanity on the other.

Could we say that you have now reinvented yourself as a poet?

Yes, that’s for sure. But when I looked back over my life I realized that I have reinvented myself many times. We all go through stages as we go from childhood to our adulthood and then we take on a job and whatever job we have, something defines us. Then, in my marriage, I’m redefined yet again and then I started to have children and when I become a father that reinvents me. I think we go through many phases of reinvention. For me, personally, I think reinvention also had dramatic overtones because I got to have success as a rock star and that was a strange, surreal kind of thing. Not like I ever believed: “Oh yes, this is who I truly am”. I never truly believed I was a rock star. I enjoyed the job, I liked it and I liked the benefits that it brought but it wasn’t who I truly was. When I reinvented myself as a poet, I think it’s fair to say that that became something that was closer to my heart and soul, that I was now becoming something that was a deeper kind of artist. I’ve always been an artist but I think artists reinvent themselves just as everybody else does.

Yes, that’s for sure. But when I looked back over my life I realized that I have reinvented myself many times. We all go through stages as we go from childhood to our adulthood and then we take on a job and whatever job we have, something defines us. Then, in my marriage, I’m redefined yet again and then I started to have children and when I become a father that reinvents me. I think we go through many phases of reinvention. For me, personally, I think reinvention also had dramatic overtones because I got to have success as a rock star and that was a strange, surreal kind of thing. Not like I ever believed: “Oh yes, this is who I truly am”. I never truly believed I was a rock star. I enjoyed the job, I liked it and I liked the benefits that it brought but it wasn’t who I truly was. When I reinvented myself as a poet, I think it’s fair to say that that became something that was closer to my heart and soul, that I was now becoming something that was a deeper kind of artist. I’ve always been an artist but I think artists reinvent themselves just as everybody else does.

I read your poem “Go Leafs Go”. Could you describe to us your feelings the first time you played at the Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto on 21 March 1978?

I’ve been very fortunate that I’ve been able to experience things that not a lot of people get to experience. That was one of them: That I was a fan of this professional hockey team that played in this building and I had gone to games there when I was a little kid and now here we were: We were going to play this building and I was going to have my name on the marquee. It was a really interesting challenge but at the same time it was a very fulfilling thing to have happen: That we played this concert and we sold a lot of tickets and it was a big success and it was a big thing in the growth of Triumph as a successful kind of business and a band that people liked. So, it was a big moment for me. I think it was also a thing that you get to put your childhood in a certain perspective. Now, as an adult things are happening to you that make you realise that you still carry the child around inside you, although that is no longer the dominant thing in your life. Even though we reinvent ourselves in new models, we still carry around our old levels inside us and that’s an important thing that I remember and honour.

You wrote in “Reinvention (Three)” regarding your departure from Triumph in 1988: “It did not take as much courage to walk away as it had been costing me humanity, sanity, to stay”. Was it staying in the band more painful for you than leaving?

Yes and that’s exactly what that poem is about: That being in the band was too high price on a lot of levels. In a very practical way, my kids were growing up and getting older and when you are in a band and you go out on the road for long tours, for big chunks of every year, that was just too high price to have to pay. I wanted Triumph to find a different life where I could be around my family, but that was only one thing. I mean, there were dozens of things. It was the political imbalance that existed in the band and its partnership. So, from the business point of view things had got way out of reach. I wasn’t just happy creatively anymore trying to make music for this thing called Triumph. I wanted to make music, write music and be responsible for my own stuff instead of having to submit it to this kind of democratic business process. That just wasn’t satisfying for me anymore. There were dozens of reasons. I mean, there was no way I was be able to extract myself from that business relationship without paying a severe penalty. It was gonna be a very difficult business, financial kind of thing when I finally said: “I ‘m leaving. I want out” just like say a divorce would be for someone. So, it was gonna be a terrible divorce, but in the end, the divorce was the thing that made the most sense. I couldn’t figure any other way around it.

In “Remembering Russell” you write about how your dying brother was the catalyst for the Triumph reunion. How emotional was it for you to play with Triumph at the Sweden Rock Festival in 2008?

In “Remembering Russell” you write about how your dying brother was the catalyst for the Triumph reunion. How emotional was it for you to play with Triumph at the Sweden Rock Festival in 2008?

That was a long, long road that led to that. But yes, the loss of my brother was a huge thing in my life because he got cancer and he died relatively young, before his 50th birthday. I would say I probably lost not just a brother but one of my very best friends and somebody that I relied on for a lot of joy in my life; because he was just that kind of a person, that he brought joy to almost everyone that he encountered. So, it was a big loss and my brother’s condition when he was sick and dying was that I should try to reconcile with my two former partners in Triumph. So, I started that process and it took years and eventually we got to the point where in order to make the circle come all the way back around, to bring things full circle, we wanted to play some shows in order to make that very real. So, Sweden was one of them and I brought some of my brother’s ashes with me when we flew over to Sweden and I put some underneath the stage, before we went on. It was symbolic but it was an important part of what I felt the path of my life, the direction of my life. It was something that I need to do to try to honour him and also to honour the idea of Triumph as being part of a brotherhood and a fraternity that had been a very important thing for me which is the point that he made to me saying: “You can’t keep carrying around all this baggage. That’s going to weigh you down and eventually destroy you. You have to try and figure out a way to deal with it”. So, it was very difficult and very emotional, but I think it was also critically important to my life.

What should fans expect from the upcoming “Triumph: Rock & Roll Machine” documentary?

Well, it’s an interesting movie, that’s for sure. First of all, I think Banger (ed: Films) are very good to what they do: The director, its producer and the editor, they have done many of these rock band documentaries, so they know what they are doing. But I think, in the final analysis there is a sense of humour to it, there is the sadness of the band breaking up and getting back together. It’s a big story that have to tell. I mean, it’s been over such a long period of time. Triumph started in 1975, so there’s like 45-46 years. It’s a lot of storytelling to have to try and cover. You can’t tell every story, but I think they did a very good job with telling the one that they decided that they were gonna tell. They are limited by the footage that they can find and the testimonial sort of interviews that they do. It’s a documentary, it’s a film, so you can only use what you ‘ve got on film. They even made a lot of animated cartoon things in order to be able to create sections of things to look at, to tell the story. So, very interesting, very difficult. I am gonna do a memoir and that will be a bit of my own private take on the story than necessarily the documentary says. The documentary is pretty good. I mean, the climax of the movie is that we did this thing for fans when we did a fan fest and we flew people in from all over the world and the band actually performed three songs live for these people in a warehouse and it was an incredible experience. It was just an unbelievable thing. So, a lot of our fans, that are really true fans, they already know how the story is going, because they were there (laughs).

Was it an interesting experience for you to collaborate with Alex Lifeson (Rush –guitar) and James LaBrie (Dream Theater –vocals) on your “RES9” album with Resolution 9 in 2016?

That was a wonderful experience. I mean, I’m so glad that Mascot gave me the chance to make a record like that, that late in life. I don’t think very many people get that kind of an opportunity. It was a good enough budget that I was able to do these things and ask these people like James and Alex to be part of a project. You are wanna know that is gonna be done right. We had Matt DeMatteo helping us produce and engineer and that guy is a proven genius. So, it was really lovely. It was great to be able to write the songs and have those guys involved creatively. I felt very lucky, very blessed to have that opportunity to do that. I think it’s a damn good record! I was disappointed that it didn’t sell well and the record company didn’t seem able to find a way to market and promote it very well, but I still think it’s a pretty good record. There are some records in my life that when I listen to them I go (ed: he mumbles): “Oh jeez! That’s not too great” It’s very embarrassing, you know, but there are other ones where I listen to them and I feel like I definitely got some things right and “RES9” is one of those albums. I’m proud of it. I think it’s a good record.

Your vocal performance on “Blinding Light Show” is amazing. Would you like to tell us a few words about this song?

Your vocal performance on “Blinding Light Show” is amazing. Would you like to tell us a few words about this song?

(Laughs) It was a song that I actually wrote in a band that I was in before I was in Triumph, which was an interesting little three-piece progressive band and the song was a little different. When we played, it was sort of more progressive in its arrangement. But In Triumph it became a song that helped break us in Texas AM radio. So, the song played a big role and in our concerts it was our big production number where the dry ice would come out and all these different lighting cues. It was a very production-oriented piece of music. It showed off that very well. The other thing about the song that’s interesting is that there is a paradox in it, it’s ironic. That is a song about being in a big show; the idea of show business as this grand circus. But the singer never feels like that’s really honest and true. The singer is singing from a point of view saying: “Don’t judge the book by its cover, don’t fall for these outside bells and whistles and smoke and mirrors. That’s not really true”. I think the paradox of being a performing artist made the song interesting and it made it an interesting song for me to sing.

The inclusion of the acoustic “Petite Etude” in a hard rock album such as “Allied Forces” in 1981 was quite revolutionary. Was it a kind of musical statement from you?

There are a couple of things about this. I mean, first of all, the big role model for me was Steve Howe of Yes and how he had songs on albums like “Clap” on “The Yes Album” (1971) and then on “Fragile” (ed: later in 1971) he had “Mood for a Day”. That was very influential for me. I always felt it was a lovely thing if a musician in a band could get the opportunity to also show his expression through a piece of solo music on an album. We were always desperate for songs anyway. We would get into pre-production for an album and we would always be searching for how we can fill up the album, we didn’t have enough stuff. We ‘d have 5 or 6 songs and we needed 9 or 10. The guys said: “Well, if you want to put a guitar piece, that’s great”. So, I felt like “Blinding Light Show” had “Moonchild” in it on our first album and then it became a sort of a Triumph tradition that there would always be a guitar piece.

I was very grateful that the other guys in the band would allow me that, would give me that opportunity and over the years I did different things, I tried different kind of pieces. It have been a chord progression in the song “Lay It on the Line” (ed: from “Just a Game” -1979), that was in a bridge of that, which is a cycle of F’s. It’s not a big deal. It’s a progression that has been around forever. It’s in the jazz standard “Autumn Leaves”. That progression it seems that is one the things that keep coming back in life that I use it as a writer to try out different ideas. When I played duo shows with Dave Dunlop, he and I would go with just two guitars. We would always do a little bit of “Petite Etude” and then we would go right into “Lay It on the Line” because there is a kind of connection musically between the progressions that occur in those songs.

Triumph played at the US Festival in 1983 after Judas Priest and Ozzy Osbourne and before Van Halen and Scorpions. Do you have any memories of that day?

Triumph played at the US Festival in 1983 after Judas Priest and Ozzy Osbourne and before Van Halen and Scorpions. Do you have any memories of that day?

Well, it was a very hot day and it was very surreal because there were so many people at this thing that it made it epic. Even just to get to the gig you had to fly in in a helicopter. So, it was unusual, it was very-very weird and surreal. Of course, with all these rock bands in the backstage area, it was crazy. Judas Priest had the motorcycles and Van Halen had a compound. It was like a hometown gig for them because they were a California band. They had actresses, actors, friends, people were coming and going, celebrities all day long and they were having a party in there, in their compound. It was loud. I was just trying to figure out how I could survive, play this show and get through it. It occurred to me that there were so many cameras. There were like, I don’t know, 9 or 10 cameras on stage and the audience was so far away because of the barricades that they had. It was hard to connect to the audience that was there but it was easier to connect to the cameras. So, in a way, some of the things that I decided to do, they were more for the cameras because I realized that they were filming this thing for big screens. It was one of the first times that they ever did this thing: They had cameras that they were putting whatever they were shooting on these big screens on each side of the stage.

I realized that this is more like you are being on a TV show than you are playing a concert to a crowd. So, that’s how I approached it. But there was a nice little moment in the documentary where John 5 -the guy who is playing with Rob Zombie and has got a lot of successful records on his own now- he was a kid watching it home on MTV and he was saying how my performance was very influential on him, which was a lovely thing, it’s a nice and it’s in the documentary movie. You know, something like that is happening on a scale that is outside of your control. So, I felt like whenever these kinds of things happened in my life, it was more a question of instead of losing yourself by the stuff that was extending way beyond you, the idea is just get down inside yourself and try to sing really good, try to play really well and just try to make that happen, because that’s a small, internal thing that you can control. All of this other outside stuff, you can’t control it, so don’t try to do that. I mean, athletes say this all the time. The coach would say to his team: “Just do you job. Don’t get so caught up in this moment of this playoff game or whatever. Don’t let it put you out of shape. Just do your job”. In the end, for gigs like that, that was my approach: Just do my gig.

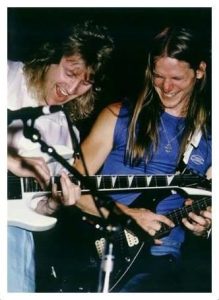

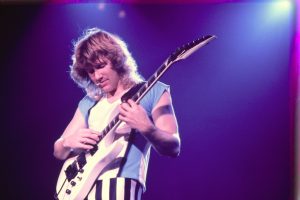

There is a nice photo of you jamming with Steve Morse (Dixie Dregs, Deep Purple, Kansas –guitar) onstage in 1987. Did you have fun playing with him?

There is a nice photo of you jamming with Steve Morse (Dixie Dregs, Deep Purple, Kansas –guitar) onstage in 1987. Did you have fun playing with him?

When that guy started to become successful and known with Dixie Dregs, I thought: “Man, that guy is such a great guitarist, he is so good in so many levels”. So, I had always wanted to meet him and he was playing I think with Kansas at the time and he came to a Triumph show and I got to meet him. Then, later on in life, the guy who was A&R man for MCA Records in the States, Thom Trumbo, he knew Steve Morse very well, they were friends and then when Thom was gonna help us produce the “Surveillance” (1986) album, the last Triumph album that I played on, he said: “Hey, do you want me to talk to Morse and see if I can get Morse to come up here and collaborate on that one?” “Oh, that would be incredible!” So, he came to Toronto, he stayed to my house, we spent like the better part of the week, I would say maybe 5 or 6 days together and we wrote and we played on the Triumph album, but we also did a live guitar festival thing in Toronto that weekend. It was one of the highlights of my life.

At that point in his life he was the kind of guy that was winning awards for being the best guitar player in the world like “The Most Versatile Guitarist in the World”, “The Guitar Player of the Year”. He was as good as good gets. The most influential guitar players in my life and I would say Hendrix, Page, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Ritchie Blackmore of Deep Purple and then eventually Morse became the guitar player for Deep Purple, taking over Ritchie Blackmore’s guitar hero model, Steve Howe , Pat Metheny. Steve Morse would be one of the guys and I got to play with him on stage, I got to write with him. It was a wonderful, beautiful experience. I should leave George Benson off that list because I went to get to play with George Benson (laughs) and that was a tremendous thrill. He is a little further outside the genre of rock and progressive rock and stuff that I played in but I would say that ranks right up there: My nights playing with Steve Morse, the night that I played with George Benson. I had some pretty great moments in my life.

What does the induction into the Canadian Music Industry Hall of Fame in 2007 mean to you?

It’s a lovely thing. I don’t want to make it sound like I take those things lightly. They are very serious and they are very wonderful, but having said all that I don’t do what I do because I want to become rich and famous. And if I do get richness from it, that’s a lovely thing, that’s a great thing, but in a sense it’s almost like a by-product of why I do what I do. I realise that this thing in show business is all about the idea of having to market things and having to try and create all these sorts of bells and whistles that surround fame and all celebrity, but I don’t do it for those reasons. I do it because I’m trying to just write good songs. I ‘m trying to play guitar really well, I am trying to write good lyrics or write good poems. I ‘m only trying to do the work the best that I can. Then, it’s about how to sell the work. I mean, I ‘m sitting here talking to you on the phone because there is a certain amount of stuff that you have to do in order to promote and market and that’s all part of how the game gets played and I understand that. It’s something you accept when you say: “Ok, I want to play the game, I want to be in the game”. It seems you have to do all these kinds of things.

There are some authors who never do interviews. They go: “No, I don’t want to talk to anybody. I don’t have to explain myself. I don’t want to try and sell myself. I am just gonna do a work and I will just let the work speak for itself”. But there is a part of me saying: “Oh, I wish I can find the courage to be that kind of person” (laughs) but I tend to be a much more practical and realistic man and my ego is not the same thing as that. When you get an award to be in a Walk of Fame or a Hall of Fame and these things it’s like people are patting you in the back and going: “Man, you are great” and then you go: “Yes, thank you”, “Yes, I am great”, “It’s great to be great”, “I love being great”. This ego-stroking kind of thing about the whole exercise and then, the next day I look at myself in the mirror and going: “What kind of personality you are?” But it’s a lovely thing, it’s a great thing. The Walk of Fame (ed: in 2019) was a really cool thing because all my kids got to come with their significant others and we all got to sit together and have a dinner together. You get to see a family taking pride in you and that’s a beautiful thing. I mean, the reason that I decided to join bands that were gonna try and become famous was because I wanted to make enough money that I could provide for my family and then I could have a big family. In the end, you are sitting in this dinner and everybody is sitting with their families and to me that’s a beautiful thing.

In 2011 you recorded Rush’s “Red Barchetta” using Neil Peart’s drum parts via Sonic Reality software. How did it happen?

In 2011 you recorded Rush’s “Red Barchetta” using Neil Peart’s drum parts via Sonic Reality software. How did it happen?

Wow, you sure have gone into depth. I got a call and somebody asked me if I felt like trying to do this thing. In particular, it was Neil Peart’s drum parts, that was the basis forwhy I was interested. I said: “You mean, the actual parts that Neil Peart actually played?” and they said: “Yeah” and I went: “Oh man, yeah! I am totally interested in that”. To get to play on top of his parts. I mean, Neil Peart is obviously one of the great, legendary drummers in rock music history, so I said: “Yes, I ‘m interested in doing that” and they said: “Ok. So, it’s possible. This software allows you to do that”. I went into studio with an engineer/producer/musician friend of mine named Mike Shotton and I did guitar and vocals. Somebody else played the bass on it, I can’t remember who (ed: Matt Dorsey). Yes, it was an interesting little side project. The thing about having a career is that you get offered things that are off the beaten track, it’s not the main thing that you do. It’s just this other side thing that comes along. But sometimes to me, those are even more interesting than going on and playing gigs all the time. The stuff that is the bread and butter is sometimes not as interesting as these little side projects. So, this was a side project that I found very-very interesting.

Of course, there was always this thing about Triumph and Rush: Two three-piece bands from Canada, power trios, you know like: “Oh, Rush is more successful than Triumph”, “Rush, they have better musicians” and I understand that human nature. That’s just something that is gonna happen. The other thing of course is that I admired Rush, it was hard not to admire them. They made great records, they had a really great work ethic as a band. I always admired the process of their own pre-production as they would go about creating a record and they all had high quality production values in everything that they did; the album covers that they made. They were a band that was like up there with English progressive bands and bands like Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin. They had that kind of quality that ranged through all of their work. I admired them. So, to get to play with Neil Peart’s tracks… and Alex and I, we knew each other, we are friends and he was fond to be able to get to play Alex Lifeson to Neil Peart. That was fun.

Who inspired you to use a talk box?

Obviously Peter Frampton, he got more commercial success than anybody else. But I think the first person I ever heard using one, might have been Jeff Beck. I think maybe it was Jeff Beck, I’m not sure. I am trying to remember who it might have been. Yeah, it had been all around and then everybody was trying. The guy in Bon Jovi (ed: Richie Sambora) also had a really successful record where he used a talk box. The first time I ever tried one I thought it was gonna knock the fillings out of teeth. I would say Jeff Beck and Peter Frampton were the two guys.

Do you think social media like Youtube and Facebook have helped young listeners to learn about your music?

Certainly, the fact that we live in a digital universe now; I mean, everything has changed and that’s the way it works. I think one of these things about growing old is that we tend to have a romantic notion about the things that we had in our youth and in my case we will romanticize that process when we were little kids and we went and bought 45s at the local department store for our little 45rpm Seabreeze record players. Then, the next step was: “Wow, now our parents were buying stereos because FM and stereo had started to become popular”. So, we were all buying vinyl albums that run at 33⅓. Now, there is this culture that was about albums and here in North America there was FM radio that started to play, became Album Oriented Rock. This was really the biggest part of the romance of music in my own life. The soundtrack of my own life was about albums and vinyl albums. So, by the time the technology has got to the point where everything is digital and people walk around with a phone in their pocket and you can have a library that is ridiculously infinite that you can access. That’s the way people now get their music and that’s how they consume it and then everybody is going to talk about it by going on Facebook and going on social media. I mean now we are living in a world where it’s like: “Oh, if you want to promote something you have got to make a 30-second video for TikTok”. Then, I remind videos from when they started on MTV, I wasn’t a fan of them, because it wasn’t a part of the romance of the way I understood “this is how music works”. This is how music goes in your ear and gets into your brain and taps into your own imagination. To me that was a different kind of process.

I’m 68 years old, so there is gonna be a part of me that goes like (ed: he mimics a grumpy voice) : “Aah, you ruin everything. All this digital stuff and all these social media. It ruins everything”. I can remember when I was a kid and you ‘d run into guys that were guitar teachers who had been jazz guys from the ‘40s and the ‘50s, so now, here was the ‘60s and these guys were relegated to teaching guitar lessons and they would be saying when Elvis came along: “That was starting to ruin the music business” and then when The Beatles came along: “That ruined everything because The Beatles are awful, the Beatles are shit”. I would be sitting here thinking: “You don’t know what you are talking about. You are only talking about a world that is already gone. It’s already finished. The world has moved on and this is what the world is like now for the young people and so you are denying youth. It’s nil history. That’s not a smart thing to do. That’s stupid”. That’s how I felt when I was a kid. I try to remind myself that’s what is happening now. This world of digital technology and social media and all the stuff. This is the world that my kids grew up in and my grandkids are growing up in and it’s not my world anymore and you just have to remind yourself: “Yeah, it’s not your world”. You have to share it with generations that come up after you. You have to share it with new technologies. You have to share it with new approaches to creativity and expression and that’s how it works. It doesn’t work the way you think it works. It has its own way of doing things. That’s my thinking on that.

Do your grandchildren know that you were a rock star in the early ’80?

Do your grandchildren know that you were a rock star in the early ’80?

Yeah! The Triumph documentary hasn’t come out yet but on Canadian Thanksgiving weekend, we had all the family over, so all my kids, all my grandkids and the Banger provided us with a link so that I could go and watch on Vimeo. I could watch the documentary with the whole family. So, all the four-letter expletives -and they were seeing them all- were bouncing off the walls (laughs). But they did see their grandfather. You know: “This is what my grandfather did”, “this is the band that he was in”, “this is the kind of concert that he played”. So, they know who I was (laughs), but that’s a kind of surreal thing. I think in the end, for my grandkids is more a question of how we are playing in the backyard, they are coming for sleepovers and just sitting and eating meals together. That’s the grandpa they know. They don’t call me grandpa, they call me Bubba. My first grandson, his name is Henry, when he was born I thought: “I want him the first word that he speaks to be my name. But he is not gonna call me Rik”. “Grandpa” is a hard word to say, but babies among the first words that they learn how to say is like: “Ba-ba-ba-ba”, so I went: “I am gonna call myself “Bubba”. They are gonna be able to talk to me. The first thing he says is gonna be my name and it will be great”. And that’s true. The first words he was able to say, even before he said: “Mama”, he was able to say: “Bubba”.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Rik Emmett for his time. I should also thank Mrs. Claire Pokorchak for her valuable help.

Order “Reinvention: Poems” here

Official Rik Emmett website: https://www.rikemmett.com

Official Rik Emmett Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/rikemmettnetwork