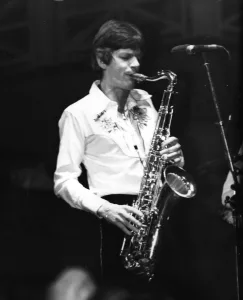

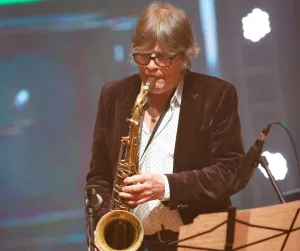

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: March 2024. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary musician: Mel Collins. He is best known as the saxophone and flute player of King Crimson in the early ’70 (recording “In the Wake of Poseidon”, “Lizard” and “Islands” albums) and then from 2014 until 2021. He has also played with Dire Straits, Roger Waters, the Rolling Stones, Camel, Eric Clapton, Tina Turner, Alvin Lee, Alexis Korner, Bad Company, Gerry Rafferty, Bryan Ferry, Clannad, Rick Wright and many others. He is currently touring with Dire Straits Legacy featuring four ex-members of Dire Straits. In late June/early July Dire Straits Legacy will play shows in Greece (buy your tickets here). Read below the very interesting things he told us:

What is the concept behind Dire Straits Legacy?

What is the concept behind Dire Straits Legacy?

It’s basically because we love to play Dire Straits music. There are 4 of us from Dire Straits. I was in an early version in 1982, when I joined. Alan Clark is the keyboard player, who was there before me and was with them until recently (ed: 1992). Danny Cummings, the percussionist and vocalist, he was also in Dire Straits and Phil Palmer, the guitarist. So, all the 4 of us were ex-members of Dire Straits and as I said, we enjoy playing the music and the opportunity came up for me to come back and play with Marco Caviglia, the lead guitarist. It was his concept, in the first place, to play Dire Straits music and we joined him 7-8 years ago and we ‘ve continued it and the audience seemed to like the way we played. We are the original members, so we are gonna play properly and the music is universal. We have all ages come to the concerts: Young, old, parents of, children of. It’s a very varied audience and they love it. They love the music, which we enjoy playing. So, that’s idea of it, really.

In your opinion what makes the music of Dire Straits still relevant 40+ years later?

Because they are good songs. Mark Knopfler (guitar, vocals) is a fantastic writer and has written so many different melodic songs as well as the rock songs. It’s relevant today as it was in the ‘80s, because of the fact that songs are so good and that comes across to the audience.

What should fans expect from the Dire Straits Legacy shows in Greece in late June?

Yes, we are playing Athens and Thessaloniki (ed: we talked on 23 March, since then Heraklion and Chania were added). They will expect or they will receive Dire Straits music at its best. Mark Knopfler obviously does his own solo tours now and doesn’t want to play that music anymore. So, we are there to fill that gap basically and they can expect Dire Straits music played well.

Is there any news from Kokomo?

Is there any news from Kokomo?

Unfortunately, Frank (ed: Collins), the singer has just been a bit unwell and Neil Hubbard, the guitarist is, because we are all getting old. As far as I know there is one concert at the Royal Albert Hall in May, which I can’t do, because I will be in Brazil with Dire Straits Legacy. But there I know they are supporting the Average White Band, because when I was touring with Kokomo in the ‘70s we did a whole tour of America, East and West, supporting the Average White Band, who had a massive hit at that time with “Cut the Cake” (1973) the album and “Pick Up the Pieces”, the single (ed: from “AWB” album -1974). We got together and we were very fond of each other, we had mutual respect because both bands played the London scene for quite some time and it was nice to join up with the Average White Band again. So, that’s the idea of that. That it’s coming up in May, which it ‘ll be maybe the last time Kokomo get together, I don’t know. Unfortunately, I won’t be there but I wish them well, of course.

Are you satisfied with the end result of “In the Court of the Crimson King: Crimson at 50” (2022) documentary?

Yes, I think we all are. We were all pleasantly surprised. Toby Amies (ed: director) did a great job. He toured with us for about a year. He came on the road, not the whole time, but at various points and he spent long hours putting it all together. To begin with, he had a problem with Robert, because Robert didn’t want to do an interview. Then, he changed his mind, later on. When Robert saw some of the rushes, you know, some of the film, he realised that it was actually quite a big project and Toby had done it really well. We were all happy with it, to be honest.

Was the three-drummer line-up of King Crimson a bit extravagant?

That was Robert’s concept and we all thought that it won’t work, we really did. We thought: “This is crazy. Three drummers?” But Gavin Harrison (ed: Porcupine Tree –drums) organised the drums, so that it wasn’t just three drummers bashing oh hey and making a lot of noise. It was all organised, all orchestrated and that then worked. We all saw that it worked really well and it was an experiment, to begin with, but it turned to be worthwhile. I think we all enjoyed it. It was loud (laughs), but it was very good and the drummers would see each other. Gavin, of course, was the technical one and Pat Mastelotto (Mr. Mister) is very much a rock drummer and then we had Bill Rieflin (ed: REM), to being with, then he got ill and couldn’t carry on, and we got Jeremy Stacey (ed: Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds) on drums and keyboards; he plays keyboards, as well. So, we had three different players that worked together very well, with Gavin Harrison orchestrating everything.

Do you think the King Crimson albums that you played on like “Lizard” (1970) and “Islands” (1971) should get more recognition?

Yeah. In fact, “Lizard” is my favourite album of all the albums. To me, obviously, they were very early days and I was pretty much employed on a session basis. I wasn’t part of the band as such, then. Apart from “Islands”. “Islands” was a band project and of course “Earthbound” (ed: live album -1972), but that’s another story. Yes, I think they are very worth-listening to. Actually, with the band we had with King Crimson, the last band, it enabled us to play a lot of that material that King Crimson had never played before live. We played a lot of “Islands” and “Lizard”, which it had never really been played before, partly because Adrian Belew (guitar) didn’t want to play it, to be honest.

You recorded “Starless” from “Red” (1974) as a session musician. How did it happen?

You recorded “Starless” from “Red” (1974) as a session musician. How did it happen?

It was in the days when I was actually doing a lot of session work, my main bread and butter was sessions and I happened to be in this studio, which was Olympic Barnes Studios and I had been asked to come down and play with Steve Marriott’s Humble Pie. So, I was in the studio along the corridor working with Humble Pie and King Crimson were in another studio, a little bit further down, and we saw each other and Robert had already asked if I would be available and of course there I was, in the studio. So I just popped down after the Humble Pie sessions into the King Crimson set up and then I played pretty much first takes on “Starless”. I hadn’t actually heard the song beforehand and I didn’t have any chance for it. It was really just improvised from my point of view, anyway. That’s how it happened.

By the way, who played double bass and cello in “Starless”? They don’t mention any name in the credits.

That’s a good point. I don’t know. I have to find out. I will tell you when we come to Athens. I really don’t know about that. I ‘d like to find out myself. So, maybe next time I will tell you.

Had you joined King Crimson when Elton John auditioned for the lead vocalist position on “In the Wake of Poseidon” (1970) sessions?

I wasn’t there, so I hadn’t heard about that before. So, that must be another story I don’t know (laughs), sorry.

How much has your relationship with Robert Fripp changed over the years?

How much has your relationship with Robert Fripp changed over the years?

Oh, 100% turnaround! It was very difficult working with him. I ‘m sure you ‘ve heard stories, but in the early days, I was young, I was 22 and a little bit too enthusiastic, I think, for Robert. Robert had his own problems, his own demons to deal with and he wasn’t very sympathetic with me at that time and he once mentioned to me that he thought I would never be a writer. I ‘d come up with some parts and some riffs to maybe turn them into a song and he refused to play them and that pretty much was the reason we finished the band at that time. Ian Wallace (drums) and me were good friends and he didn’t like the way Robert was talking to me and eventually I left the rehearsal studio in tears and I thought: “That’s it, I can’t work with Robert anymore”. He did actually ask me when we finished, we had actually to do another tour of America, which we were contracted for. At the end of that tour when we were going separate ways, he asked me if I would continue with the band; he intended to put another King Crimson formation together with John Wetton (Family -bass) and Bill Bruford (Yes -drums) and in the end David Cross (violin) etc. But I said “no”, I didn’t really feel that I could continue with him because I had a lot of music to play.

I wanted to try different styles, I played with Clannad for 10 years, the Irish band; I played with Pino Daniele in Italy, also for a long period and these were all different styles of music, which was great for me. I love to learn and play in different situations and in different environments. I even played with a Spanish heavy metal band, Barón Rojo, in the ‘80s. I did a whole tour with them, which was a bit strange because people didn’t really want to see a saxophone in a heavy metal band, but I did it. I did it my way. What actually happened was: Jakko Jakszyk (vocals, guitar) put this new band together in 2002 called the 21st Century Schizoid Band and that was with Michael Giles, the original drummer, Ian McDonald, the original saxophone and flute player and then we took this band on the road. At the beginning of that, Robert had heard about the idea of us putting something together and Jakko had been in contact to make sure that he approved of the project. Then, I got a call from Robert, so this is like 30 years later, saying that he was sorry to have hurt me, at that time, and sorry for all the mean things he said to me which cleared the air and started a kind of new relationship, which eventually led us forming in 2014 the new King Crimson line up and he had changed completely. He had been into so much, I imagine and I’ve heard that he had changed, he was very nice to me and we became friends, would you believe (laughs). Yes, that’s what happened. That’s how it changed.

Did you enjoy jamming with Steve Marriott (Small Faces, Humble Pie -vocals, guitar), Alexis Korner and Boz Burrell (King Crimson, Bad Company -vocals, bass) during your last US tour with King Crimson in the ‘70s?

Yes, that was great. I think we were all so wound up with King Crimson and Robert and working with him on stage, which in those days was so difficult. If you made a mistake, he would be there on his stool glaring at you. You knew you had made a mistake, Robert was telling you. That was what I was living up to (ed: to jam with Alexis Korner, Steve Marriott and Boz Burrell) : The fact that it was so relaxing to go back to the hotel and have two drinks and then get the instruments out and we would play, as you say, with Alexis Korner, who was “The father of white man’s blues”, as they used to call him in England and Alexis was a catalyst for a lot of musicians. He put all sorts of people together and he did the same with us, with Boz and with Ian and we had that band called Snape (ed: Alexis Korner & Snape -“Accidentally Born in New Orleans” album -1972), which we took on the road and there is a double album actually (ed: Alexis Korner & Peter Thorup with Snape -“Live on Tour in Germany” -1973) somewhere with Snape and it was fun. Getting back to King Crimson at that time was so tense on stage. We enjoyed going back and playing with the other guys who were on the tour. It was actually a package tour with Humble Pie headlining, then King Crimson, then I think was Black Oak Arakansas, an American band and the Alexis Korner & Peter Thorup (guitar, vocals) who opened the show. So, it was a great tour and we had a lot of fun, as you can imagine.

Is there any update on the album you are making with Jakko Jakszyk (King Crimson -vocals, guitar)?

Is there any update on the album you are making with Jakko Jakszyk (King Crimson -vocals, guitar)?

Yes, we are just starting that project to re-issue “A Scarcity of Miracles” (2011) and there are a lot of outtakes on that: I played different instruments on different tracks. At the time, we picked the best and that was the album. But now, we are re-looking at it and we are beginning to record some stuff. Also, the newer material that we are putting together with King Crimson. We will be doing an album with those songs.

Who will be the other musicians?

Gavin Harrison, myself, Robert, probably Tony Levin (Peter Gabriel, Stick Men –bass), maybe Pat Mastelotto as well. We will see how it develops, but it’s a project to look forward to. King Crimson is not dead yet (laughs), you know, it’s going on. Robert does like to change his mind quite a bit and I think he is very enthusiastic with this idea, so there is something to look forward too.

So, there will be one album with the outtakes and a separate new album or all in one?

No, there will be two separate albums. That’s the idea at the moment. So, it’s a re-release of “Scarcity of Miracles”, then we ‘ll see how we go with the new material with King Crimson.

What did your playing add to Stick Men when you toured with them in 2017?

I had found it difficult because we didn’t have any rehearsals and they play together so often and for quite a few years now. I found it difficult to add to the band, so I’m not 100% sure what did I add to the band. I would have liked to have had more rehearsals and worked out some ideas, rather than going in just for a jam, which is how it was, really.

How much artistic freedom do you have on other people’s records?

How much artistic freedom do you have on other people’s records?

Usually, people get me in for what I do. The sessions aren’t the same, anyway. There aren’t the sessions like I used to do. I ‘d do 3 or 4 sessions every week, possibly more. My father (ed: Derek Collins -saxophone, he toured with Judy Garland and Shirley Bassey) used to do 3 or 4 sessions every day (laughs) in the ‘50s and ‘60s, but these days there is hardly anything. I occasionally get to work for Cleopatra Records in America. They put out albums, for example, William Shatner, Captain Kirk (ed: from “Star Trek”), you know, did a Christmas album (ed: “Shatner Claus -The Christmas Album” -2018), which I’m on a couple of tracks. They send me files and I have a listen to them to decide what instrument to play and what to play on the tracks and send the files back. That’s Cleopatra Records. But very few sessions now, to be honest and if there are I’m usually asked to do something with a new project, when there is no much money available, which I’m happy to do. So, I don’t get so much work session-wise, anyway.

Was it an interesting experience to tour in 1985 with Roger Waters when Eric Clapton was in his band?

That was a very strange situation. I think Eric was not very happy with it. He just got over his problems and came on the road with us and of course it was almost one long song, the album “Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking” (1984). Eric wasn’t so keen. It was ok, we had a good time, I got to know Roger very well, but then it wasn’t a huge success. I have a lot of respect for Roger because he took it on himself to do this solo thing and in Pink Floyd nobody knew their names really, in those days. So, we were going to America and people were saying: “What are you doing?” and I said: “I am playing with Roger Waters” and they said: “Roger Waters?! Who’s that?” They didn’t seem to know his name. He worked to that, to build the name up and build the name up until now, where he is a huge success again. We saw him, actually, he was staying at the Sunset Marquis in California and playing one of the stadiums there -I can’t remember what it was- and we came in with King Crimson, we were playing the Greek Theatre and Roger was staying at the same hotel. When we arrived, we went to the gig, somebody knew somebody who could get some tickets and we went in and we saw the show and he was there for a few days. We were just in and out, but that night Roger heard I was there with King Crimson and invited me over and we had a great chat and we renewed the friendship, which he had before, in the days when I was not actually such a nice person (laughs), but anyway, that’s another story. So, Roger is a very strong character, as you know and he’s written some great songs and it was interesting working with him and hopefully I will work with him again at some stage.

You ‘ve said that when he started his solo career was a victim of the anonymous image of Pink Floyd. Did he have a lot of pressure to become known to the audience?

Yes, very much so. In fact, there is one tour we did when Pink Floyd were actually on the road three weeks behind us and I know Roger were pressurized, he would look at the reviews. They were similar shows, in some respect. Obviously, Roger would be playing Pink Floyd tunes, of course, that he wrote, so, there was a lot of comparison and that was pressure on Roger, really was. But he got through it and he ‘s doing really well now.

Did you have fun making the “Rain Dances” (1977) album with Camel?

Did you have fun making the “Rain Dances” (1977) album with Camel?

Yes, that was a great time, actually. I am thinking back to it now: I didn’t realise how good the music was. I had come from King Crimson and I was a bit prejudiced when it came to prog rock. I thought Camel were good guys and they had nice songs. Andy Latimer (guitar, vocals) in particular was a great player, he had a nice sound, but I wasn’t convinced about what we were doing. But my girlfriend actually who I met in Chile and is a Camel fan has played me some of “Rain Dances” and the live stuff we did, that’s a BBC concert that we did (ed: “BBC Sight & Sound –Live at the Hippodrome 1977”) and it’s good, I was really surprised. They were a good band and those were great songs, so I am a convert with Camel.

I ‘ve watched Camel’s “Total Pressure -Live in Concert 1984” (2007) DVD and your guest performance in “Rhayader Goes to Town” at the Hammersmith is fantastic. Please tell us a few words about your approach to this?

I lived in Chiswick, which is actually just down the road from Hammersmith where the Apollo is. Andy and the band were coming into town to play the Apollo and because it was being filmed, they asked me if I would like to come and play with them, just to feature on a couple of songs and that’s what I did. I went down and again, there wasn’t much of a rehearsal, it was a run-though and at the time I wasn’t very happy. I ‘ve always been so critical of myself and I thought I hadn’t played very well. In fact, to the point, I was soaking in the dressing room a little bit and Andy introduced me on stage and I was still in the dressing room, so I don’t think I peed (laughs), which was a bit stupid because it’s pretty good as you kindly said. So, it was another one where I get asked at the last minute to do something and then I don’t have enough rehearsal time in my mind, but actually often it works out really well, because I have more of an improvisational way of looking at it and sometimes I play better like that, to be honest.

I know that Eric Clapton was really supportive to you when you played in “Core” from “Slowhand” (1977). Is it flattering that people like Eric Clapton respect your talent?

Yes, he was very nice to me. I got called in and Eric was doing this album, “Slowhand” with Glyn Johns, as a producer and he had this one track, which he wanted to put the saxophone on, but he was doing it live in the studio with his band, which we used to do a lot of that as you know in those days. It was much more of a family thing in the studio, all together playing live rather than overdubs and overdubs. So, Eric showed me the song and it was an American band that he had at the time and they were actually a little bit cold towards me, with this white, longhaired young saxophone player from England and I don’t think they thought I was very good. But Eric was very-very kind and he sensed what the situation was and we went over to the pub together and he invited me with him and he said: “You know, Mel, you ‘ve got it! I’ve played with King Curtis (saxophone), I’ve played with Aretha (ed: Franklin), I ‘ve played with this and that and you ‘ve got it, boy!”, which was very sweet of him. It took three days to get the song finished, because Eric had his problems at that stage, but he was so nice and he played great. You can’t take that away from him. It might have been in the pub some of the time but he still played great. He relaxed me, basically, because I was extremely nervous with the situation and not really being in the band again, it was difficult, but it’s ok, it worked out.

Were you surprised when Mick Jagger asked you to record “Miss You” (1978) with The Rolling Stones?

Were you surprised when Mick Jagger asked you to record “Miss You” (1978) with The Rolling Stones?

Yes. I was in France, I was in the same country, I was working on Rick Wright’s solo album “Wet Dream” (1978), which has recently been remixed, actually, and I finished with Rick. I think I was there for two days, I went over with Snowy White (ed: Think Lizzy, Pink Floyd), the guitarist and I played all over that album. I had got a call from Mark Fenwick, who was the manager for Roxy Music, at that time, and I had been on the road with Bryan Ferry (ed: Roxy Music -vocals) on his first solo tour. That was 1977 I think and the connection was Chris Kimsey, who was the producer on The Stones’ next album (ed: “Some Girls” -1978) and they were in Paris and I was in Nice with Rick Wright doing this album. Then, I was asked to go in the studio with The Stones which was very exciting for me; I always had an ambition to play with The Stones. So, I left Rick Wright and I went up to Paris and I was put in a hotel and I was told that Mick (ed: Jagger -vocals) had just finished doing some of the tracks on the album and he wanted to have a rest. So, we would just wait in the hotel. The call came through a couple of hours later: Would I hang on, because Mick wasn’t ready yet? This went through the night. I ‘m there half-asleep waiting for the call. It went right through to the next day; they were working 24 hours a day in this EMI studio in Paris. Eventually, I got a call to go in about 4 o’clock in the afternoon the next day and Mick was there with Jerry Hall, at the time, and Jerry Hall had been the road with Bryan, it was the tour I did before, so I knew her.

Mick was a little bit uncertain about me, he didn’t really know anything about me, but we went in and we recorded “Miss You” and we tried different things and different instruments or whatever and one by one, the other Stones came in. Ronnie Wood (guitar) came in, I knew him quite well and he came over and said “hello”, it was a big studio and he set up in the corner with his own charge. Then, Keith (ed: Richards) came in and Keith walked towards me and I went to shake his hand and he walked past me to the back of the studio and sat on a stool reading the Melody Maker and completely ignored me, which was very off-putting, but I ‘ve since realised that his man was Bobby Keys (saxophone), that’s his soulmate. If you read his book (ed: “Life” -2010), Bobby Keys was banned from The Stones at that time and Mick wouldn’t have him in the band, so, Mick had gone ahead and booked me through Chris Kimsey, the producer. I ‘ve worked with Chris on Bad Company and other projects. So, Chris had recommended me. Anyway, it went through and tried another track, which I even forgot the name of the song, but it worked out ok. There was a coffee machine also in the studio and people were wandering in getting coffee and sandwiches from this area at the back of the studio. Of course, I am trying to play the solo of my life with all this going on and then Keith comes in and ignores me. So, it was frightening, to be honest (laughs), but that’s the story behind that.

Were you frustrated with Keith Richards’ behavior towards you when you recorded “Miss You”?

It was disappointing, yes. I didn’t know what was wrong and obviously there was a whole thing going on and as I said, they had been in a studio for 24 hours for three months, every day, at some stage. Now I know, that Mick and Keith weren’t talking, so, for Mick to go ahead and book me without probably consulting Keith, was too much to bear and I guess that what the problem was. But, yeah, it was disappointing because I didn’t know Keith and I ’ve got a lot respect for him and I ‘ve seen documentaries now and Keith always comes over really well. So, I think it was one of those unfortunate things and I just happened to be the wrong person there at that wrong time. But I ‘m quite happy I’m on the album, it ‘s quite an accolade for me.

What was like to play with your first professional band the Dagoes at Star-Club in Hamburg in 1965?

What was like to play with your first professional band the Dagoes at Star-Club in Hamburg in 1965?

Oh my God, it’s such a long time ago! Yeah, I was playing with this band, they called themselves the Dagoes. It was four Anglo-Indian guys and two white British guys and we actually had a great time and for me this was the start. We got a gig in The Star-Club where The Beatles played in Hamburg and I think we did a month’s residency in there and we were not very good, that’s for sure. Somehow, we got there and we turned professional and then we came back from that and there wasn’t any work. The other guys just went back to their normal jobs and because my father was a musician and my mother was a singer and it’s in the family, I was gonna stay professional and fortunately I could, because my parents were still supporting me, I was only 18 then. So, I didn’t have to go back to work, but I was professional and I was gonna stay professional and that’s it (laughs). It was good fun, it was an eye-opener to the world in Hamburg. It was incredible; stuff we hadn’t seen before, you know.

You played on Bob Dylan’s “Desire” album. Why weren’t you credited on this?

There were so many musicians involved. We went in as Kokomo and I think Bob Dylan was trying to find another line-up similar to The Band that he had before. He wanted a band and I think he tried the Dave Mason Band before us in the studio, which it didn’t work out. Then, Kokomo, we are playing in New York at the time, so it was a nice thing to be asked to do, just pop down to the Columbia Studios and did these sessions with Bob Dylan. Eric Clapton was there, I couldn’t tell you now the different musicians that were there that I didn’t know and the trumpet player, Mike Lawrence and we were put together without ever having played together and it was actually quite an enjoyable occasion. Bob would just walk around the studio with a few chords and show us the song and we then have to do it and we do it in one or two takes. We never got into the control room, because that was full of people, so, we never heard any of the tracks back. That was the first day and then some of us were asked back for the second day and some weren’t and Bob did the same thing again the next day. We really had no idea what happened: Whether I’m on the album or not, I don’t know, to be honest. None of us know today.

Do you have any memories from the 21st Century Schizoid Band show in Athens in 2003?

Yes, that’s the first time I ‘ve been to Greece or any of us, I think. That was the beginning of it, really, and the project was very new and we were ok, we were working it out with Michael Giles (drums), Ian McDonald (saxophone, flute) and myself. The idea of us all playing together was a bit strange to begin with, but Jakko (ed: Jakszyk -vocals, guitar) was determined to put this together and Michael Giles is his father-in-law, actually. So, Athens was great but there is a whole story of Jakko not being able to fly over because there was a problem with the airlines: They wouldn’t accept Jakko’s guitar on board and he didn’t have a hard case for it and he couldn’t let it go in the hold, so Jakko missed the flight, had to go home, get a hard case and come back later on and get another flight, which he managed to do so and came over at about 10 o’clock at night the day before the concert. So, that was the start of it, but the gig itself I think it work out pretty good.

Who are your early musical influences?

I was a big fan of Paul Desmond, the alto (ed: saxophone) player who wrote “Take Five” and played it with the Dave Brubeck Quartet. Stan Getz, very much the cool (ed: jazz) school, as they were called in those days, some from the West Coast of America, very musical, melodic players and that was a big influence to me. In fact, you can hear my playing on “Cirkus” (ed: from King Crimson’s “Lizard” -1970) actually, the alto solo I do is very much Paul Desmond (laughs). I’m sorry to have to admit but that was my influence. Then, I had already discovered Charlie Parker and John Coltrane and they became my heroes and Sonny Rollins and there are tons of them. My father was a saxophone player, that really started it all and a great clarinetist, actually, Benny Goodman-style. So, I grew up with that and listening to big bands. When the Rolling Stones and The Beatles came along, I decided that I wanted to be a rock ‘n’ roller. That’s the only reason I didn’t become a jazz player as such, which is the way I play now. But they are my influences: Stan Getz and Paul Desmond, definitely.

Did you have a good time touring and recording “In Flight” (1974) live album with Alvin Lee (Ten Years After -guitar, vocals)?

Yeah, that was great, actually. That encompassed three Kokomo singers (ed: Dyan Birch, Frank Collins, Paddie McHugh), as you probably know and some good friends of mine: Tim Hinkley on keyboards who I’m still in touch with, he lives in Nashville now; Ian Wallace of course, from King Crimson and Boz (ed: Burrell -King Crimson, Bad Company bassist). That was a circle of us, all playing gigs together, a lot of it jamming or whatever. We would play anywhere at any time. We just loved playing, really. So, Alvin was part of that circle and we got on very well. Unfortunately, when we went on the road with the band some members couldn’t make it; I think it was just me and Ian actually from that band, a keyboard player called Ronnie Leahy (Stone the Crows) and a bass player called Steve Thompson (John Mayall) and a couple of backing singers and conga player and we went off to America. Alvin was managed by Dee Anthony, who was a big manager in those days. He managed Humble Pie and Peter Frampton and Supertramp, I think, in the end, in America, anyway. It was a lot of fun. For me, it was great to be playing some of the old rock ‘n’ roll stuff that Alvin loved: Elvis and a lot of his songs from the rock ‘n’ roll era. So, we had a lot of fun with that. Unfortunately, there was a problem: Ten Years After were so big after Woodstock and everything, but to go out as a solo artist as with Roger Waters, it’s very difficult. You have to build that up: People know Ten Years After, they don’t know Alvin Lee, so you have to keep working at it and it was just didn’t work out. I think we had the band for about six months and then it petered out, really.

What was your reaction when you learned that your father, Derek, would play on The Beatles’s “Savoy Truffle” (from “White Album” -1968)?

Oh yeah, I didn’t know about this. It’s only recently that I found it out. He didn’t tell us. He was working all the time as I mentioned before, working with all sorts of people and I didn’t see him. He was out, working. So, I didn’t know anything about this until recently. My girlfriend showed me a line up of sax players that had played with The Beatles and my father was in (laughs), as you say. This is quite recent for me, I didn’t know it.

How important is improvisation to you?

It’s everything, really. I’ve never been a very good copyist when it comes to solos. For example, Roger Waters when we played “Money”, which of course is one of his famous songs, he wanted the solo exactly the same and I can’t do that. I don’t do that very well. I’m too much of an improviser, so we had a problem with that. I did the best I could at the time, but the solo was from a guy called Dick Parry who played with Pink Floyd quite a few times and toured with them in their heyday and he was in the studio with them and recorded that solo. Also, it was in seven (ed: 7/4), later on the guitar solo is in 4 (ed: 4/4), but they left the sax player to try and get through this 7/4 time signature and that is not easy, to try and copy a solo and get it note to note. I ‘m sure a lot of people can do it, but I don’t do it very well, so I’m an improviser; that’s what I do. I would go in the studio and people used to say: “Can you play like David Sanborn?” The answer to that is: “Well, if you want David Sanborn, book David Sanborn or Wayne Shorter or whoever”. It’s not the right thing to say to somebody who is good at improvising.

What was it like to grow up in London in the swinging sixties?

What was it like to grow up in London in the swinging sixties?

It was a lot of fun. It was great and I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. It was fantastic time. I don’t think we realised how great it was but we certainly had a lot of fun and a lot of good music. In fact -digressing a little bit- the jazz scene in England was very healthy then. There was Keith Tippett (piano), John Surman (saxophone, clarinet), Alan Skidmore (saxophone), all these young players playing jazz in a new way and not necessarily influenced by rock or anything, but there was a sudden crossover later on with rock and jazz, fusion and whatever. But at that time, it was very healthy. I would go and see the bands when I was 18 and 19 and nobody would come with me because it was jazz. I used to see Tubby Hayes (saxophone), Ronnie Scott (saxophone), John Surman, Alan Skidmore and Keith Tippett. It would be great to go and see all these players playing improvisational music again, the most of it and that it really influenced me, as well.

I know you loved working with Gerry Rafferty. What’s so special about him?

Gerry Rafferty had a wonderful voice, he was so musical. His soul used to come through his voice, you could hear his soul. Him and Pino Daniele from Italy were the most musical artists I worked with and Gerry especially. I was just sorry that I didn’t do “Baker Street” (ed: from “City to City” -1978), that was unfortunate, but I got to play on stage with him and he was a real friend and somebody who I always considered to be the best and most musical artist I ‘ve worked with.

Was there any kind of competition between you and Dick Heckstall-Smith (Colosseum, John Mayall -saxophone)?

Actually, no. He wasn’t at all like that: He was the nicest man. I didn’t get to know him very well because he was before me, really, a few years older than me, but we did play together a little bit. Unfortunately, I wish I played with him more. I just missed that time with Alexis Korner and The Graham Bond Organisation with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker , of course. That was just a little bit ahead of me, before I was on the scene and I used to go and see those bands, but I wasn’t really part of it and it was only later on that I met Dick through Alexis Korner again. As I say, he was such a catalyst for musicians, but I didn’t know him very well. There was certainly no competition there, at all.

Have you ever thought to write your autobiography? It would be very interesting.

Have you ever thought to write your autobiography? It would be very interesting.

I ‘ve been considering it lately. It’s a lot of work, but I think I should do that. Thank you for mentioning it. I have to. There are a lot of stories and a lot to tell. So, yes, I would love to. I just have to get off my back, so then I’ll start writing.

Do you think popular music in the ‘60s and ‘70s was much better than today’s music?

I think songwriting was better. The pop music of today, we all have trouble relating with these Korean boy bands and girl bands and the Japanese-style pop is something that I don’t really relate to. It doesn’t have the soul that I look for, that I mentioned before. I would have to hesitate to say it was better then, but it was (laughs).

You used to go to the Speakeasy Club. Did you get to meet people like Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon, Keith Moon, Ginger Baker who hung out there all the time?

Again, that was just a bit before me. They were all down there probably 5 or 6 years before I got there, so I didn’t really get to meet anybody. Also, I ‘m not the most pushy person, I wasn’t in those days, I was quite shy, so I never really got to meet them, to be honest. I did some work with George Harrison in the studio, a band called Splinter that he was producing and I got asked to do some horn section work, to write horns for some of the tracks. So, I went down to meet George at his house, the Friar Park, which was a great experience for me and he was so lovely, he was very nice. We went into the studio and listened to the tracks and then of course I was in the studio but I didn’t see him after that and most of the guys had retired or were in America or in different circles from those days when everybody went to the Speakeasy. So, I was too late again.

Are you optimistic about the future of progressive rock?

Are you optimistic about the future of progressive rock?

I think so. There is a huge market now that has developed which we got into with King Crimson working for seven years on the road, touring everywhere really, apart from Australia, we didn’t tour Australia or New Zealand. We found the audiences growing and growing and the whole scene is building up which shows that people want to see live music and they want to see the players that are still around, of course. So, I’m quite positive about the whole scene. I think there is new generation of people that are interested in playing which lead them to come and see bands like King Crimson. It’s still there, for how long I don’t know, but I feel positive about it.

Why don’t you have a personal website or a Facebook page?

There again, that’s another thing which people ask me and I wasn’t really so interested in that. I didn’t think there were enough people for me to wanna talk to or reach out to and it’s only recently, to be honest, with Dire Straits Legacy that I find going to gigs and I have people outside waiting for me with an armful of albums for me to sign and this has happened recently quite a bit. It’s irritating for the other guys in the band, who they are all sitting in the van waiting for me and I’m signing all these albums (laughs). So, I think that’s due for revision, as well. I should really think about making it happen or getting somebody to help me with the website.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Mel Collins for his time. I should also thank Sid Smith for his valuable help.

Official Dire Straits Legacy website: https://www.dslegacy.com/

Official King Crimson website: https://dgmlive.com/

Official King Crimson Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/kingcrimsonofficial/