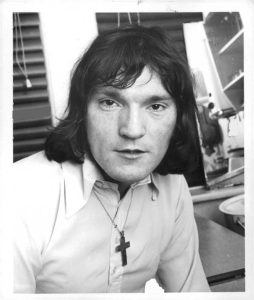

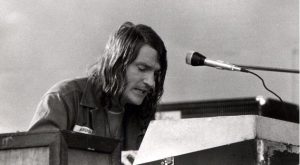

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: June 2014. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary keyboard player: Brian Auger. He has done numerous amazing albums with his bands Oblivion Express and Trinity. He has also played with Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, Sonny Boy Williamson, Rod Stewart, Eric Burdon, John McLaughlin , Eric Clapton, Tony Williams, Steve Winwood and many others. His latest studio album is called “Language of the Heart”. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

Are you satisfied with the feedback you got from fans and press for your solo album, “Language of the Heart”, released in 2012?

Are you satisfied with the feedback you got from fans and press for your solo album, “Language of the Heart”, released in 2012?

Well, we don’t have a record company at the moment, but that album did sell very well when we were on tour. Most of the fans, bought it. I’m very happy with that album. I think my favourite track on it, is “Ella”. And the reason for that was because the track just came out of the air basically. In the beginning of that project, I went to the producer’s house, Phil Bunch and I found Franck Balloffet (guitars) and I sat down and they were running the tape. Ι was just feeling about and I played these chords and they saved it, and they kept referring to this as “The Ballad” and I said: “What ballad?” We hadn’t even started yet and they said: “Oh, we put this thing on tape that you did”, but I said: “Yes, but I was just playing about”. They told me: “Listen to it” and I had a listen and I liked the chord sequence. I wrote down a chart with the chords on it and I thought: “I don’t know what I am gonna do with this”. And then I remembered an old album by saxophone player, Stan Getz. The album was called “Focus” (1961) and a string arranger arranged it with the track, and just presented it to saxophone player with a chart, with the chords and they ran the track as he played over the chord sequence. It was absolutely amazing. So, I thought to myself: “Ok, bring the track up and I’m just gonna play over the chord sequence”, which I did using the Rhodes in the beginning and then playing over the chords. And all came surprisingly. I think it has a lot of passion on it and a lot of beauty. It’s just one-off. “Language of the Heart”, man. Really, that it was. “Ella” is my wife for some 44 years this year. So, I decided to call it “Ella”. I’m never dissatisfied with the reaction to albums because there are certain albums that I made in the ‘70s and the ‘60s that sold poor and people want them. It seems to pick up different generations as it goes along. I don’t worry about that. I just worry that the tracks that we would put, have a meaning to them, they mean something to me. Each album is like a page in my musical diary: Where I am musically at that time. I am not looking to write something for any kind of need in the marketplace or anything like that. I am just trying to make the best music that I can make and put it out there. “Language of the Heart” is available on Amazon and also from my website at www.brianauger.com and we had tremendous sales of that when we were on the road. I’m totally satisfied when people meet me and ask about that and about different tracks. In the song “Flying Free”, I wrote the lyrics and my daughter, Savannah, came and helped me with the vocals and we had Jeff “Skunk” Baxter from the Doobie Brothers, a great friend of mine, playing on one of the tracks and Larry Coryell’s son, Julian Coryell, a wonderful guitar player, he came and played. And Karma, my son, played drums and percussion things. I enjoyed the experience. I thought we did very well, indeed. Out there in the record company world, I didn’t expect any response for something like that. Music now is on a lot of hip-hop and a lot of other pop stuff and the big labels are only interested in that. I’m still interested in real music. That is what the album represents. I think music is “Language of the Heart”. I live in Venice, California, I got down to the beach when nobody is there in the morning and walk around there and I try to get some silence and some stillness inside and then the music comes of itself. I can actually hear the music. To me, music is also a language. If it comes from the heart, then it’s language of the heart. And that’s why I named the album.

What are your projects for the near future?

I’m going out in July and August to Europe. In Italy, Germany, Austria, Belgium. And maybe we are going to Spain, although that it may happen in November and we have a very strong public out there and we always have a great time. I have been offered to do three concerts next year with a 50 piece Symphony Orchestra and we are trying to pick up the tunes that I will play and give me the arrangements on them. There is a lot of stuff that goes into when we are going to do something like that. We are still talking about to get over with the promoters, but that’s gonna be a nice project. I was very lucky this year, very honoured to be inducted to The Hammond Organ Hall of Fame and also to The Hungarian Rock ’n’ Roll Museum Hall of Fame (laughs)! It’s a bit strange, but anyway I really appreciate those people. We toured this year in the U.S. I am writing my autobiography as well, so it keeps me off the street corners.

Are you proud of the classic status that the album “Open” (1967) has until today?

Are you proud of the classic status that the album “Open” (1967) has until today?

I don’t know what that is, man. I don’t know what the status is out there. People called me different names but what I do notice is that those albums were made about 45 years ago and yet we carry them with us when we are on tour because people ask for them all the time. For example, in Europe people still want to hear the tunes we did way back. Two years ago with my daughter, Savannah, we decided to do a Mod Party album, again available on my website, and we re-arranged all those tunes that they wanted to hear and made an album of them. And when we did the Mod Party tour in Europe for two years, it was absolutely amazing, because I was playing the intro to “This Wheel’s is on Fire” or the intro to the “Road to Cairo” and people would stand up and applause because they recognized them and that was what they wanted to hear. And we played a lot of the other tunes and some of the B-Sides that I had never played live before and that was an incredible success. I like to mix things up and I like to move on and do fresh things. The live album (ed: “Live in Los Angeles 2013”) with Alex Ligertwood. We recorded it and we put it together in a week, before we went to Europe. That was incredibly well-received. We are talking with a record company at the moment to put that live album out. I started Oblivion Express in 1970. In 1972, Alex was working with Jeff Beck and left the band. We heard that he was around in London and I invited him to come to Oblivion Express. I thought he was one of the best singers around. He also plays guitar and percussion and his voice is like having another instrument. It’s phenomenal. We did “Second Wind” album, a couple of live albums… In 1977, I had been on the road for 16 years at that point, with no break. I was exhausted, I was 38 years old and for the first time in my life I didn’t want to play anymore. And I didn’t play for nearly a year. I thought I ruined my passion. But it came back, fortunately. In the meantime, we were living in San Francisco and Alex called me and asked me what I was doing because he had an offer from Santana. I told him to take the offer. And he was with Santana for about 16-17 years. He recently stepped back from that and we only live one mile from one another here, so we are always in touch and I asked him if he would like to come out with us for a tour and he accepted and we had a great time. And my son said: “Dad, we should record the band live with Alex”. So, he got that together, he’s a great engineer. We came all together and we played in a club in Los Angeles and that is the origin of the “Live in Los Angeles” live album. And Alex is still an amazing singer.

Why did you decide to cover “Light My Fire” on “Streetnoise” (1968) album?

Well, I heard that track first on The Doors album in 1968 and people said: “Have you heard this guy who plays keyboards with The Doors?” and I said: “No”. I bought that album and… I didn’t like all the songs. I don’t know, maybe I was a bit of Jazz snob at the time and I didn’t get it. Julie (ed: Driscoll) said: “Have you heard Light My Fire?” I said: “Yes, on The Doors album” and she said: “No, no. Have you heard the version by Jose Feliciano?” and I said: “No”. And she brought the single over and put it on and when I heard that I said: “That was a fantastic tune! We have to do that”. It was a psychedelic time at the time and we were in the studio and I was playing around with it and we decided to do it as a sort of psychedelic thing and slow it down and what it came out, it’s just what it came out. We listened to the take and we decided to keep the take. I don’t know if we could do any better than that and people still ask for that. And we play it here and there over the years, particularly when we had Savannah in the band because this song really needs a female voice. It’s amazing that last month in Rolling Stone magazine, the Rolling Stone people decided that they would make a Top 20 of all the albums that they love from the ‘60s, but people apparently never heard (laughs). I know that sometimes it takes a long time to get recognition. “Streetnoise” is one of these albums. So, I had people calling me and saying: “Have you seen Rolling Stone? It has “Streetnoise” on the Top 20”. Anyway, people learn about it a long time later, but it’s still very satisfying to have people appreciate that after all these years and it still has a strong following. The double album (ed: “Streetnoise”), a lot of the people at the time really loved it. People like Richie Havens and many others. I did a version of Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage” in 1969. That was 4 years before Hancock. Over the years, he became a great friend of mine and he still is one of my favourite jazz piano players. When I first met him he said: “He’s the guy that put my tune!” And that was a kind of –I don’t know how you would call it- jazz, funky version of “Maiden Voyage” from the “Befour” album. Yes, a lot of things came on at that time.

How important is improvisation for you?

How important is improvisation for you?

It’s always important. It’s absolutely important. The reason I keep as much room for solos is because improvisation is where everything grows, all new ideas. Sometimes, I get the impression when I am soloing that I have an almost magic moon. I get the impression when I am looking at my hand when I am playing and I’m certain that I cannot make a mistake. I am also at the same time thinking: “Who’s doing this? Who is playing this? I’m just looking at my hand!” There is a certain magical music. It’s like when you are dialing in a radio station and you get your line through. Then the music comes through. So, when you get your mind and feel out of the way throughout your career, sometimes the real creative stuff comes through. If you look at the great composers, someone like Mozart he really improvised in his mind and he was writing down the orchestrations of the things that he was thinking. It’s all improvisation. The same thing with Beethoven. He was playing music in a small room at a party, or something like that and he said: “Ok, give me 3 notes or 4 notes” and he would improvise something out of that (laughs). Just like the jazz guys who are improvising, all the great composers improvised and they were able to orchestrate their improvisations. In fact, all the great stuff comes from there. So, I can keep a lot of room for me and the guitar player’s solos and everybody else, simply because a lot of great ideas come out from an improvisation and so music goes on and refreshes itself. It’s still my passion after all these years. I like to play live, doing sessions and play music that really has soul.

How did it happen to jam with Jimi Hendrix at The Cromwellian Club in 1966? He had just moved to England.

At that time, in the ‘60s before anybody got insanely famous, everybody knew everyone. We all used to jam and there were some amazing jams going on. One of my friends, was one of the guys from The Animals. I knew Eric Burdon, with whom we played in the ‘90s, I made friends also with Chas Chandler (bass). And Chas called me and asked me about come up to the office because he wanted to talk to me, which is a strange thing because I told him: “Why you called me on the phone? Say it now”. He said: “No, no”. Chas wanted to talk to his boss. I really didn’t like Chas’ manager (ed: and Jimi Hendrix’s co-manager), Mike Jeffery, I thought he was one of the biggest crooks on the scene, somebody to stay away from. So I said: “I will come up, I’ll talk to you and… whatever” (laughs) I realised that whatever it was, with Mike Jeffery involved, I wasn’t going to do it. Anyway, I came up to the office and I had just started the Trinity, so I had Julie Driscoll, a guy called Vic Briggs on guitar, Clive Thacker on drums and Roger Sutton on bass. A very strong band and my idea after coming out of The Steampacket, was to start that band. What I wanted was a drummer who could crossover from the jazz into the R’n’B world, and someone who could play like Bernard Purdie, that was what I was looking for, and a bass player that listened a lot to James Jamerson, who was the bass player on all the Motown records and have a rhythm section like that. A guitar player and a great singer to do positive songs with positive messages. And I was already in rehearsal and playing with that band. And what they said to me was: “We brought this fantastic guitar player over from New York and we would like him to front your band”. And I said: “Julie Driscoll fronts my band and I already have a guitar player and you suggest me to fire those people (laughs). You are talking about this guy: I have never heard him, I don’t even know what his name is, but I tell you that” –this was probably Monday or Tuesday at the week- “Bring him down to The Cromwellian on Friday, when we are playing there”.

And The Cromwellian was a late night club and everybody from the scene when they were doing their concerts in London and around, would make it to The Cromwellian because they could get a drink until maybe 2 o’clock in the morning and food. I think on that evening, Eric Clapton was there, Jeff Beck was there, Alvin Lee was there and people like Steve Winwood and even people like Lulu. Not to drop names, but that was the kind of scene. All these people from the recording scene, from the music scene. So, I said: “You know, bring him down there and he could sit in with my band and everybody would see it”. It was a kind of logical pact, and they brought Jimi down and in the break I had a word with him and he seemed like a really nice guy. I said: “Ok, Jim you wanna play with this?” “Yes”. When Jimi told me that he was going to play then, he borrowed my guitar player’s amp, cranked it up at number 10, he put the guitar in, and he told me: “Can you play this sequence of chords?” and he showed me a sequence of chords, which was of “Hey Joe”. I didn’t know “Hey Joe”, I didn’t know how it was called that, but he just explained me the sequence of chords and I said: “Yeah, that was really cool. That’s great. Give me a tempo”. And he came in and we started to play and everyone said: “Who the hell is that guy?” What I realised at the time, was that I hadn’t seen anything like that. He was playing blues, but it was a very progressive way of playing blues with also a lot of other ingredients. I realised that the guys that were watching, Clapton and Beck and everybody, British guitar players had not quite come to themselves at that point. You could hear their influences of Freddie King, B.B King, Albert King, Robert Johnson and all the other blues players. You could hear that feel. Apparently, when he played that tune everybody was shocked. They wondered: “Who the hell is this guy? Where he come from?” He stayed to play some other things with us and I understood from Eric Clapton, apparently went home and nearly stopped playing. He thought: “I am finished” (laughs). And fortunately, he continued to play and as you know it, he became a tremendous player. And all the other guys who were there. At that particular moment, it was something else. It was a voice that was inside him and we hadn’t heard anything like it. And Jimi became a big friend of mine, and he would find out where I was playing in London and he would come and sit it at Blaises, at The Bag of Nails, at Scotch Of St. James, at the Carnaby Street and when we started to get famous, we all ended up going to America and I didn’t see him again until…

And The Cromwellian was a late night club and everybody from the scene when they were doing their concerts in London and around, would make it to The Cromwellian because they could get a drink until maybe 2 o’clock in the morning and food. I think on that evening, Eric Clapton was there, Jeff Beck was there, Alvin Lee was there and people like Steve Winwood and even people like Lulu. Not to drop names, but that was the kind of scene. All these people from the recording scene, from the music scene. So, I said: “You know, bring him down there and he could sit in with my band and everybody would see it”. It was a kind of logical pact, and they brought Jimi down and in the break I had a word with him and he seemed like a really nice guy. I said: “Ok, Jim you wanna play with this?” “Yes”. When Jimi told me that he was going to play then, he borrowed my guitar player’s amp, cranked it up at number 10, he put the guitar in, and he told me: “Can you play this sequence of chords?” and he showed me a sequence of chords, which was of “Hey Joe”. I didn’t know “Hey Joe”, I didn’t know how it was called that, but he just explained me the sequence of chords and I said: “Yeah, that was really cool. That’s great. Give me a tempo”. And he came in and we started to play and everyone said: “Who the hell is that guy?” What I realised at the time, was that I hadn’t seen anything like that. He was playing blues, but it was a very progressive way of playing blues with also a lot of other ingredients. I realised that the guys that were watching, Clapton and Beck and everybody, British guitar players had not quite come to themselves at that point. You could hear their influences of Freddie King, B.B King, Albert King, Robert Johnson and all the other blues players. You could hear that feel. Apparently, when he played that tune everybody was shocked. They wondered: “Who the hell is this guy? Where he come from?” He stayed to play some other things with us and I understood from Eric Clapton, apparently went home and nearly stopped playing. He thought: “I am finished” (laughs). And fortunately, he continued to play and as you know it, he became a tremendous player. And all the other guys who were there. At that particular moment, it was something else. It was a voice that was inside him and we hadn’t heard anything like it. And Jimi became a big friend of mine, and he would find out where I was playing in London and he would come and sit it at Blaises, at The Bag of Nails, at Scotch Of St. James, at the Carnaby Street and when we started to get famous, we all ended up going to America and I didn’t see him again until…

..John McLaughlin was mixing his “Devotion” album.

That’s right. Exactly. John was an early guitar player that I knew since we were both 17 and we used to go out every weekend and play gigs together. John invited me to go down to the mix and the door opened and in came Jimi. He was with his girlfriend and he was at a bad shape at the time. Alan Douglas, who was the producer and the engineer, they were very-very rude to Jimi, and that was very unnecessary and it was like you are just the new guy and you are finished. I really didn’t like that and I asked Jimi: “Let’s talk outside”. So, we went outside and in the light I saw that Jimi’s skin had a kind of grey colour. And his girlfriend was looking the same, you know. He asked me if I could stay and make an album with him. I said: “How long it will take?” and he said: “Maybe 2-3 months”. And I said: “Jimi, I have signed a contract back in Europe and if I don’t show up they are gonna sue me and I will be bankrupt. I would love to do it but I can’t for the next 3 months”. At that point, he put out a silver paper and he started to snort what was obviously heroine and he offered to his girlfriend and then he offered to me! I said to him: “Listen man, for God’s sake, leave that stuff alone because it will kill you”. He already looked bad enough, and Jimi said something that I will never forget: “You know what, Brian? I need a lot more people around me, like you”. And he invited me to see his studio, Electric Ladyland, the next day and we were jamming at night. Just turning the tape on, without playing anything. The jams were ridiculous improvisations but there were no songs, no melodies and tunes. I think he used a lot of it for the Band of Gypsys album. Then, I got back to England, and in less than six months since I last saw him, I heard that he finally died in London. I was shocked and I was so sad to hear that. Because it was such a waste of a great talent. And I have thought that if he had survived, we probably would get together and done a lot of things over the years. Now, I don’t have to worry for that.

Did you enjoy the recordings of Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Don’t Send Me No Flowers” with Jimmy Page in 1965?

Did you enjoy the recordings of Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Don’t Send Me No Flowers” with Jimmy Page in 1965?

Yes. Sonny Boy was in London, before he played at the Marquee. He stayed at my manager’s house at the time. The first time I heard he was in town, there was a place called The Crawdaddy Club in Richmond. And suddenly I heard this chuckle behind my back and I turned around and it was Sonny Boy getting his harmonica out and he played the whole set with this. And we would find out where he was playing and would come and sit in. I just had my first Hammond organ, I had a Hammond organ trio at the time. So, I made friends with Sonny Boy and he was quite a character, man. Very few people know that he had a pocket inside his frock coat and he used to keep a bottle of Johnny Walker in there. And he would put it out in the middle of the gig and take a shot of. I thought that he was an amazing character. I asked him at one point: “Sonny Boy, would you mind if I ask you how old you are?” and he said: “Well, I don’t really know” (laughs). He said something I think: “They didn’t keep any records of us when I was born”. He was from the Black community, of course. That was a strange thing and the other one was: “Sonny Boy, you keep singing “Come up at Saturday night fish fry”. What was that?” and he said: “Hey man, that was a lot of fun because everyone was getting out of the work in Friday afternoon and there was a time of a lot of food and fish and we had a big cooker of fish, and we had a big party from Friday night all the way from Saturday, all the way from Sunday, and we cleared up on Monday morning when we had to go to work. And when we cleared up on Monday morning, we always found a couple of dead bodies” (laughs). That was quite surprising. I said: “Well, I ‘ve been to a lot of parties, Sonny Boy, but maybe we didn’t party so hard” (laughs) He was a tremendous character. He got a job in the States, on a radio station called, The King Biscuit Hour and told me that he was leaving. And he was leaving on a Monday afternoon, at about 2 o’clock the plane was going. Then, I called my manager and I said: “Please, when Sonny Boy leaves, I am sure we never gonna see him again” because who knows how old he was. Anyway, I asked my manager to book some studio time, which he did. I think it was Pye Studios in Marble Arch and I called up the musicians: Joe Harriott, a wonderful West Indian saxophone player; Alan Skidmore, a great tenor saxophone player; Jimmy Page who did a lot of blues sessions around town and the people that I was working with: Micky Waller on drums, Richard Brown on bass and I was playing the Hammond. And we jammed the whole album. Nobody knew what we were going to play. I think I asked him: “Sonny Boy, what do you want to play?” and he said: “Pam-pam-pam-pam. Parap. That’s it”. That’s all we had to work with it. And we made everything up. Most of it was like that. Except one that he wanted to play, I think its lyrics were: “Don’t Send Me No Flowers, when I’m in the graveyard, ‘cause maybe then I can’t smell a thing”. I knew this thing. I think we put just a blues thing over it, and he sang over it. You could almost recite it and after that was finished, immediately he went out and got into a taxi and took him to London Airport and put on the plane. He was so weak. We never saw him again. He did the radio station thing, The King Biscuit Hour for some time. I think he had a bad fall and apparently never recovered. I was very sorry about that. He was a great guy. He was a very nice guy. And he was really a window for me into the Black community in America and how hard times they were having, even at that time. Anyway, how much incredible music they produced and a lot of rock ’n’ roll people, I mean everybody, the whole blues scene, the whole rock ’n’ roll scene, they came out of the Black American artists. I think we actually copied it. I remember asking Herbie Hancock at one point: “How did you do this?” and he said: “We are covering songs and all different things. It’s all music. It’s music from the Black community. It’s something that it happened to it, until you guys came and took it into the fresh air and gave a different kind of feel to it”. That’s the only answer I got and I didn’t get it from anybody. That was from somebody who really knows his music.

Can you tell us a few things about your friend Brian Jones? You listened to music together. I know that.

Yeah. Brian was really the guy who put together the Rolling Stones and at some point, I don’t know what happened, maybe a rift between him and Mick Jagger. He didn’t leave, I think he was just kind of pushed out. At the time, he used to hang with us, when we were in town. We stopped at Zoot Money’s place, and we would bring over people from the clubs that we hung out with and jamming with. For a while, Brian would come with us. And Zoot Money would play records all night and there was a Fender Rhodes that we would play, and just had a great time and a good laugh with everybody. So, he was around with us, and he was into heavy pills, heavy downers. I think they were called Mandrax, something like that. I thought of myself: Jazz guys supposed to be druggies but no. There wasn’t that stuff going on (laughs). Unfortunately for Brian, at one point I think he took a couple of these pills, fell asleep at the edge of the swimming pool and nobody knows what happened. I think maybe he turned over in his sleep. That was bad. When I heard that Brian Jones died, I thought it was such a great shame for a musician friend to die at so young age. Anyway, The Stones are still going but I have good memories of hanging out with Brian.

You knew everybody. Who is the most talented person you’ve seen in your life?

You knew everybody. Who is the most talented person you’ve seen in your life?

Oh, my God! That’s really difficult. I don’t know how I can say about the most talented person I have ever seen. I can tell you this: I was asked by Earth, Wind & Fire in the ‘70s to open for them in about 12 concerts in the American Midwest. It was packed with their followers and what was amazing, was that when we were setting up for our soundcheck, Maurice White (vocals) and a couple of the other guys including the keyboard player, came down to say “hello” and shake hands and Maurice was very-very nice to us. He said: “We are so happy that you agreed to come, we love your stuff and I ‘m sure that the crowd will really appreciate your music” and we had a great time. That was the most amazing musical band that I have ever seen. They were so incredible. The horn section, the guitar player, the bass player, the rhythm section. The singing was incredible on stage, it was perfect. I was just blown away. They were perfect. The crowd loved the songs that they did. I stayed on the wing every night when they went on. I was just blown away. I thought: “This is the best moment in my life. Maybe I die and go to heaven” (laughs). They were so cool to us. They were very nice. That was a great honour to be asked by them to open for them.

Did you get to know Vincent Crane (Atomic Rooster, Arthur Brown)? Did you like his music?

Yeah. He was a different kind of player. I used to meet up with Arthur Brown and I saw them quite a few times. At one point, we were on the same concert at The Roundhouse in London. I think we were also at Alexandra Palace. There was a concert there with a lot of different bands and Arthur Brown was on. With Arthur Brown, he was amazing. I suppose one would call him a “gothic-oriented” player. I don’t think he was great in the jazz world that much with his playing. But he had a style of his own. I met him a couple of times and it was a very nice time to meet him. And Arthur became a friend of mine. I saw him recently, about three years ago in Germany and we actually did a concert together. Anyway, that was Vincent. He was definitely a guy worth-checking out.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr Brian Auger.

Please check out www.brianauger.com

Buy Brian Auger’s album “Language of the Heart” on Amazon here