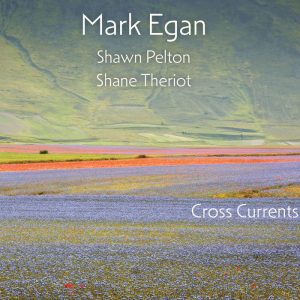

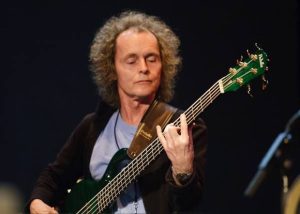

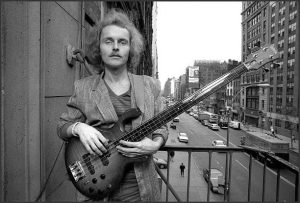

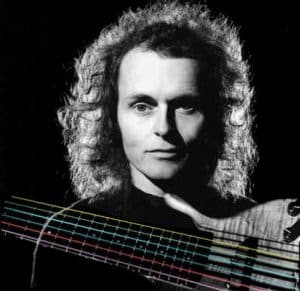

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: February 2026. We had the great honor to talk with a legendary bass player: Mark Egan. He is best known as an original member of the Pat Metheny Group and Elements. He has also played with the Gil Evans Orchestra, Sting, Bill Evans (Miles Davis -saxophone), John McLaughlin, John Abercrombie, Randy Brecker, Larry Coryell, Pat Martino, “Blue” Lou Marini, Joe Beck, Joan Osborne, Sophie B. Hawkins, Roger Daltrey and others. In 2024, he released his latest solo album, “Cross Currents” with Shawn Pelton (Bob Dylan, Rod Stewart -drums) and Shane Theriot (Hall & Oates, Dr. John -guitar) on his own Wavetone Records. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

Congratulations for the “Cross Currents” album! It’s amazing. Please give us some very basic information about the writing and recording process of “Cross Currents”?

I really like “Sand Castles” from “Cross Currents”. Please tell us everything we should know about this piece.

It’s sort of a take on Jimi Hendrix’s “Castles Made of Sand”; I just called it “Sand Castles”. Not that I tried to copy that but it has a Jimi Hendrix sentiment to it. I started playing with the groove. A lot of times when I write, I’ll come up with a groove on my computer here behind me. Right now, I’m in Florida. I spend the winters in Florida and the summers in Connecticut area, in New York area, but from both places I fly around everywhere. So, I’m centralized here for those months. Getting back to “Sand Castles”, I could play the fretless melody on, but it still has a strong groove on it and the solo section is a hint at “All Along the Watchtower”, as far as the chord changes, but I modulated them in the middle of each solo, so, it keeps feeling like it lifts and makes a change and it was fun to play on it. It was a very songful song for me. I’m glad that you liked it and picked up on it.

You can almost sing the bass melody on this.

Yes, I think that element of my playing carries across a lot of my records but especially on this one, because it’s so exposed: There is no saxophone playing a melody. When I play bass generally, a big focus for me and something that I spend a great deal of time on this, is developing how to play a melody on the bass and especially on the fretless bass, but on the fretted bass as well, it doesn’t matter, I want it to be like a vocal, like I’m singing through the instrument. That’s my ultimate goal, just to be doing that and not thinking, just singing but through the instrument. I think a lot of that comes from the fact that I was originally a trumpet player when I grew up in junior high school and high school and then, when I actually started studying music at the University of Miami, I studied jazz there, I was a trumpet major but I switched my major to bass because I had been playing bass since I was 15, anyway, so, it carries a lot of that. When you play something like a trumpet you are very aware of how you articulate a melody. A funny thing that I learned from playing with Pat Metheny, especially with the Pat Metheny Group, was how Pat was so beautiful in expressing a melody; how we would play and approach notes from above and below. So, it’s something that I do spend a lot of focus on this trying to really express a melody.

As I mentioned earlier, they are both incredibly talented musicians. I met Shane earlier through other records that I’ve done and some other playing around the New York area. He brings a lot of his New Orleans roots, but he is also a very deep harmonic player in the jazz tradition, he knows the tradition of jazz and he listened and studied people like John Scofield and Pat Metheny and he is very well aware harmonically of what he hears and also he is a great composer. Not only did he bring his great playing but as I composer he contributed the first song which is “Ponchatrain”, the opening track, so, it’s written by him and that set up the whole mood of the whole record. It gave it a great groove, but at the same time it had a nice flow to it. He contributed as I mentioned other songs and he’s also a producer. He works with Daryl Hall from Hall & Oates as a musical director; he worked with Dr. John as a producer. So, he’s not only just a player; he’s a producer, an arranger and a composer, so, he brought all those things to the record. He’s also a really nice person, he is so intuitive and he listens. He brings up good ideas and he’s always willing to try new things. For this particular recording, we rehearsed one time at my home studio which is near the studio in Connecticut, so, we just spent a day.

I make a rough sketch of the song, a demo and then I write a chart, it doesn’t follow the demo, but it’s an arrangement of what I think they are gonna do in the studio. I’m always flexible, so, I have charts written out with the chord, the melody, the form and repeated sections. I leave things loose so that if something feels that we get in the studio and that section should be 8 bars longer or just cut 2 bars, we will do that type of thing. So, Shane did his homework and Shawn Pelton, the drummer, I’ve done a lot of work with him over the years since the early ‘90s, I think, when he first moved to New York. I did a lot session work, recording studio work with him and as you know, he’s played with everybody from Bruce Springsteen to Pavarotti, he’s the steady drummer on Saturday Night Live for 34 years. So, he is an amazing groove player but he’s also very knowledgeable about the whole music world, he’s so diligent and did so much work ahead of time; I sent them the charts two weeks before we did the sessions and he came in and he had everything marked out, he knew the type of the basic groove he was gonna play, so, when we rehearsed that one afternoon, he had his complete drum groove ready to go, so, it made it very easy for me because I had written bass lines like the “Cross Currents” bass line (ed: he sings the melody) : “DUM/ badù-dù di-din-di-pa-dín/ PAM/ padu-du-dít”.

He wrote drum parts that were great and he came up with things that I wouldn’t have thought of, so, I adjusted my parts to go with him, because as a rhythm section, especially of drums and bass, you have to be flexible, but you have to be like one. And he is very aware of it and I’m very aware of it, so, he did great and when they went into the studio, Shane brought a lot of guitars: He had a Strat, a 335 Gibson, some acoustic guitars, actually of mine, that I brought, it was easier for him. I have a very nice Martin and a very nice Velasquez nylon string guitar which he played. Shawn when we got into the studio he spent a few hours tuning his drums up, he had a massive drum set. I think you can see him in the booklet, some of what he did. He is so serious, they are both really serious guys, so, when we got there we had a mission, we knew what we wanted to do and we just started doing takes and I’d say maybe we did two or three run-throughs and then we recorded and those are the tracks. I wanted to orchestrate it, so, Shawn, the drummer, added percussion and maybe an extra snare drumming section and Shane, the guitar player, I wanted to do some rhythm guitar behind it and some volume swells, just to orchestrate it, whatever the song called for. I just didn’t want to keep it just purely three people only playing; I wanted it make it orchestrated, so, it was a great experience.

It was a very conscious decision. When we were putting the songs together I had sent Shane and Shawn some of my songs and I asked them if they want to contribute whatever they wanted to and Shane sent me a couple of ideas that he had and he wanted to have my input, to co-write some things. I really listened closely because I wanted it to be a concept and not to be too different and too esoteric, so, one of the things that carries through everything is the thread of the way that Shawn Pelton played his drums. His groove is so strong that that’s within everything, even though some of the songs are more ballad-like like “Sand Castles”, some of the other songs are more aggressive, but yet there is always this thread. I wanted to go for a bluesy sort of Americana rock, but with a very open ECM Records type of sound on top, with a lot of the ambience and the different guitars and the solos and extend things off. I think it carries the thread of my past projects of how I like to write and play bass melodies and solos, but it also brought in more of the rhythm & blues of Shane and Shawn and the rock elements of me. I come from rock as well as jazz, I grew up listening in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s to Jimi Hendrix, Cream, The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Rush, Stevie Winwood and all the different bands. I’m leaving some out, there are many more that I listen to, but I also listen to Ravi Shankar and Miles Davis a lot and all the great bass players going back into jazz and going back to James Jamerson on electric bass. So, all those influences are in my playing. Even though, this “Cross Currents” has a broad spectrum of styles, someone might say, it’s not all high energy, there are peaks and valleys which is something that I like in a record because it gives you (ed: surprised) : “Oh, what’s that?! Ok, now we ’re gonna settle down” and that’s just the way I hear things.

Was it an interesting experience to play with John Abercrombie on your “As We Speak” (2007) album?

Oh, John Abercrombie! I love his playing, I’ve always been a huge fan of John Abercormbie, ever since listening to him on ECM Records and then when I moved to New York, I did some playing with him: There was an all star guitar night with John Abercrombie, Chuck Loeb, I think it was John Scofield and Vic Juris. John has always been one of my favorites. Having played with Pat Metheny and being part of the ECM Records stable of players, having recorded with ECM myself with Pat Metheny, we did two records, I was always aware of John and I love his quartet, his trio, all of his recordings and also the Pat Metheny Group toured in Japan with John Abercrombie’s group. It was a double-billing. John Abercrombie’s group with George Mraz playing bass, Richie Beirach on piano, who is another one that we lost recently, a great, master-master musician. So, when I wanted to do that trio record in 2006-7, I was thinking: “I really like to play with Danny (ed: Gottlieb -drums) and John Abercrombie” because we had played some before and we had a great rapport, so I started writing with John in mind and I started listening to his records to hear the atmosphere that he liked to play in, so, I wrote inspired by him.

I had several songs of mine that hadn’t been recorded that I thought that would fit well with that record and it was pure joy. We recorded at my studio in Warwick, New York, engineered by Richard Brownstein and Jeff Ciampa, a great guitar player and we did it in 3 days and most of it, in that case, were first takes and many of the compositions were improvisations that we did so everyone got co-writing credit on it. One song was called “Summer Sand” and everyday we’d just recording the first thing and tried to come up with improvising, because John was so good at that, he was such a great improviser and Danny, as well. So, when we did that, we just rolled the digital audio and Danny might come up and start playing (ed: he mimics a fast drum sound) : “Tú-kuti-tak-tin, tú-kuti-tak-tin” and then John just played a couple of notes and then we were off to the races (laughs). I figured out what key he was playing and it was just beautiful. Very free playing but everyone has such sensibilities of forms and dynamics and respecting and supporting the other players, while at the same time leading the other players. So, there was a really great chemistry with that trio and you know, I love to play with Danny Gottlieb, we play together for so many years and we are such a team.

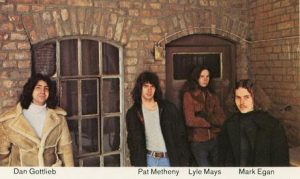

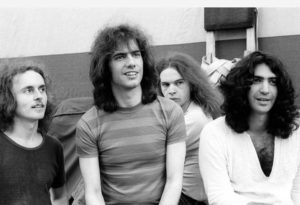

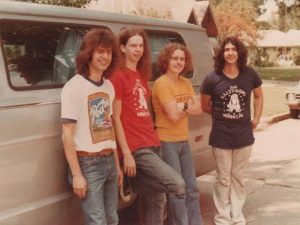

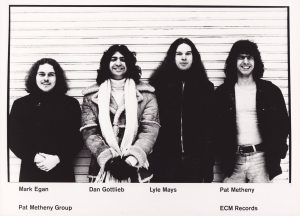

Danny Gottlieb and I first met at the University of Miami in the early ‘70s, we were studying jazz and we’ve been playing together ever since, it’s been probably 55 years. In Miami, at the university, we played with a big band, the jazz band, doing many gigs around the Miami area. There were a lot of opportunities for musicians to play on all the hotels at Miami Beach in the early ‘70s. There was a ton of work, all the major acts, national singers, all the national acts went through those hotels and we‘d play backing them up and usually it was one act a week, and you had to learn the music on the first rehearsal and then we’d play it for a week or two weeks and I did a lot of those with Danny, so it was on-the-job training, plus we just did a lot of creative playing in that period. So, we played there and then Pat Metheny decided to put together his Pat Metheny Group after he did the “Watercolors” album in 1977 and Danny and I were working up in Montreal with Lew Tabackin a great saxophone player and Toshiko (ed: Akiyoshi -Tabackin’s wife), a piano player, we played live at a venue there. I remember at the time I was playing with David Sanborn (saxophone) in New York, I had become established since 1976 and Pat called me and asked me if I wanted to join the band, the Pat Metheny Group, at that time there was no group really, it was the first Pat Metheny Group.

He had done the “Watercolors” record with Eberhard Weber on bass, Lyle Mays (piano) and Danny Gottlieb, so he wanted to start a new group. At first, it was a very difficult decision because, as I said, I was very established in New York, I was doing a lot of studio work and I was playing with the David Sanborn band, we just recorded with David Sanborn, but we rehearsed one time in Boston, Massachusetts at Danny’s house with Pat and Lyle and I was blown away. I said: “I have to do this, this is the most creative music that I’ve ever been involved with”, not that with David Sanborn wasn’t creative, but it was a different thing. So, we started playing on. Danny and I, from all the university times, we played together with all of the Pat Metheny years, for four years 300 dates a year on the road, 300 gigs a year; that’s a lot of gigs! Every year, 300, all over the world. Oh my gosh! I mean, we started out in 1977 in the spring, we travelled all that year, we hadn’t recorded, that was all in the States, starting in a van and then in January of ’78 we recorded the first white record (ed: “Pat Metheny Group” -1978) and that was the first time I had been to Europe and then we started touring in Europe, we were still in a van and we were back in the States still in a van and gradually we got a driver to drive the van, but we set up our own equipment, we didn’t have roadies or anything.

They were all the top musicians of New York and it was an improvising ensemble. We played Gil arrangements and then they opened up and there were five or six solos in one song, so, as a rhythm section player you really have to come up with different things and change it up, because every solo has a curve to it; you are following these people and going and then you come down and it’s a new solo, what are you gonna do? You are not gonna do the same thing, you got to change it up, so we had so much experience playing with Pat before, but now we were totally free because with Pat it was very controlled, it was a controlled freedom. But with Gil it was a voluntary discipline, you knew that Gil was here and Gil Evans was at the highest level of musicianship, he was Miles Davis’ mentor, it was such an honor to play with Gil. So, we had that respect for Gil, we didn’t want to mess it up, but he gave us the freedom to do whatever we wanted to do, anytime, “play whatever you want”, but you are playing with these great musicians, so we grew further that way. I have to say that when I first started to play with Gil Evans, I played with Adam Nussbaum, he was the drummer and Adam Nussbaum and I have a great rapport together as a drummer and bass player.

Adam and I did the same thing that later, when Danny came in, we just catapulted: Help the soloists and try to do different things, take different places, cut out, go into a reggae groove, play funk, go into double-time swing, the soloist wouldn’t know it was gonna happen, they just had to react to it, so, it made it interesting for us. Getting back to Danny with the band, we carried all those things. So, talking about my relationship with Danny as a rhythm section, we did a record in 2020 called “Electric Blue”, it’s just drums and bass duo. It’s on my label, you can find it at https://markegan.com/wavetone/ . It’s on iTunes, Apple Music, Spotify and all the outlets. It’s just duo, it’s Danny and I playing, it was during Covid, so, right before Covid happened, we went into my studio and recorded for about four days and then during Covid I edited it, fixed things and added things and bass and it came out. I actually released it as a vinyl, as well. It’s a great testament to our relationship as a duo playing drums and bass.

In the early ‘70s, ’71-’72-‘73, around that time period, it was when I met Jaco. He was teaching at that time -not full-time- at the University, but he came in and taught lessons as adjunct faculty. I had heard him playing with the great Ira Sullivan (trumpet), Joe Diorio (guitar) and Bobby Colomby (Blood, Sweat & Tears -drums), they were playing at a small club and Jaco wasn’t known in the world. It was really Miami where he was known from and then people had heard about him because he travelled with Wayne Cochran & C.C. Riders as a bass player, Wayne was a singer. It was R’n’B music and luckily I was in Miami at the same time and I would go hear Jaco and I was blown away! It was revolutionary music to me. I had been listening before that to contemporaries like Stanley Clarke with the early Return to Forever with Airto (ed: Moreira) playing drums and I was so into that. I was playing acoustic bass (ed: double bass) and electric bass and I was listening to all the upright players before that, because I started studying the music of Ron Carter (Miles Davis Quintet), Dave Holland (Miles Davis) and going before that, Charles Mingus, going back to the beginning of upright bass, Jimmy Blanton with Duke Ellington, all the great bass players.

I was totally enamored with Paul Chambers and I studied his music and listened to everything he did and I was so into Paul Chambers on upright bass that I got a big picture of him from one of his album covers and I blow it up and it was in my apartment. I said: “I worship Paul Chambers” and transcribed a lot of the walking bass lines that I had heard on Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue” (1959) with “So What” and that period of time, that really opened me up. So, when I got with Jaco, I just wanted to study more; I had been studying with a good teacher named Don Coffman, who at that time wasn’t at the University but he was a private teacher. As I mentioned, I started on trumpet and I was a decent trumpet player, I was an improviser and I played a lot of different shows and everything on trumpet, so, I transferred a lot of that knowledge to bass, so, I knew scales, triads and arpeggios, but I had to find out where they were on the bass and learn the bass fingerboard and what it was about. Don Coffman taught me that and I had started playing a lot of gigs before I met Jaco, but when I got with Jaco they were supercharged lessons because he was a very energized Type A personality. When I first met him at one of these places that he played with Ira Sullivan during a break I said to Jaco: “That was incredible, amazing music!” and he said: “No one is playing like I’m playing. I’m the best bass player in the world“. He had a huge ego.

And he was! I mean, there is no “best”, but he was one of the greats. It might have been smoother to say: “I’m one of the greatest”, but besides that you just had to appreciate his energy and his will of where he took it and he took it to a new place. You listen to all types of music and you hear Jaco-isms not only in the bass but in the groove. Something that a lot of overlook is: He wasn’t just a virtuoso bass player, which he was, but he played with such a groove, he came from the groove up. Everything that he played was incredibly musical, incredibly in the groove and as a result of that, melodic, because he studied Bach’s “Cello Suites” and “Chromatic Fantasy” that he recorded on his record (ed: “Word of Mouth” -1981). So, the types of things that I learned from him when I studied with him were: Major scales, minor scales, we played thirds, fourths and he would work on grouping like 5, 10, played diatonically, so, in the Key of F, it would be F, F major, G minor, B-flat major, C7, D-half diminished [Dm7(b5)], D-minor, E-half diminished [Em7(b5)] and then F major, but: one… five…. ten, going up the neck like that (ed: he mimics the note playing on the fretboard during our Zoom conversation), he would do that in major and minor. We worked on the song “Dona Lee” by Charlie Parker (ed: recorded on “Jaco Pastorius” -1976). The one thing that I didn’t know about from playing on the trumpet, was the energy, the passion and the dedication that you put in, because if I took a lesson with him for an hour, I would be playing 8 hours a day until the next time I saw him.

I was so energized and I realized that if you want to be good, you‘ve got to put the time in a huge way, because there is no easy way of getting good. You know, someone like John McLaughlin, has practiced and practiced and played and practiced and studied as anyone at a high level has gone through it. You don’t just wake up and start playing like that. Certain people, they have perfect pitch, that’s a gift, but you have to play, whether you are studying with a teacher or whether you just listen to records and you pick it up. Jaco, in his case, I think it was a combination of both. Ηe lived in an apartment next to Alex Darqui, who was a keyboard player, he was playing with him, he got a lot from Alex. He taught him harmony and different modes of improvisation. Jaco was like a sponge and whoever he played with, he was inquisitive and he would ask: “What’s that?”, “what is that?”, “how do you play that?”, but it wasn’t just asking, he would do it and his mind would take it and take it to a new level, because his creativity was on a high level. He wrote so many beautiful songs, if you listen to his composition with Weather Report “Havona” (ed: from “Heavy Weather” -1977), masterpiece, and the songs on his own records. My time with Jaco was very inspiring and as I said, it was the early years, it was before he was taking drugs and drinking, he was completely straight, he was into athletics, he played baseball, football, frisbee, whatever, and he bragged about that, he would say: “I don’t do drugs, I don’t do anything”.

So, fast forward a couple of years, he joined Weather Report and that first record came out with Weather Report, “Heavy Weather” that just put him on the world map of everything that was happening musically in the jazz world and that really was one of the key things that broke him out. At that time, I remember I was listening to a vinyl and transcribing “Teen Town”, learning “Teen Town” and listening to “Havona”. What I learned from Jaco is not only the technical side of it, the melodic side, but the groove side and the creative side of composition. Even in his solos, if he was playing at someone else’s song, they were very compositional because he thought that way and he was a very melodic player. I learned a lot, but I also learned that I didn’t want to sound like Jaco, which is very tricky, when you are playing fretless bass because as soon as you play a fretless bass, because even if someone in the bass shop would play a note and it just goes: “Whaaaaa” and you’d say: “Oh, that’s Jaco!” But when you listen to the new ones in the style of Jaco you can hear the way that he articulated into different melodies, the way he played around melodies and his sound was completely unique: If you hear Jaco, you say “That’s Jaco!” There are people that are very close, but you know when you hear Jaco. So, when I first started playing fretless with the Pat Metheny Group, it was very tricky because Jaco recorded “Bright Size Life” (1976), Pat’s first record and we were playing a lot of the songs from “Bright Size Life” as well as from “Watercolors” (1977) which was Eberhard Weber, so, for me I had to do it in my own way and I didn’t want to articulate like Jaco and I don’t.

So, fast forward a couple of years, he joined Weather Report and that first record came out with Weather Report, “Heavy Weather” that just put him on the world map of everything that was happening musically in the jazz world and that really was one of the key things that broke him out. At that time, I remember I was listening to a vinyl and transcribing “Teen Town”, learning “Teen Town” and listening to “Havona”. What I learned from Jaco is not only the technical side of it, the melodic side, but the groove side and the creative side of composition. Even in his solos, if he was playing at someone else’s song, they were very compositional because he thought that way and he was a very melodic player. I learned a lot, but I also learned that I didn’t want to sound like Jaco, which is very tricky, when you are playing fretless bass because as soon as you play a fretless bass, because even if someone in the bass shop would play a note and it just goes: “Whaaaaa” and you’d say: “Oh, that’s Jaco!” But when you listen to the new ones in the style of Jaco you can hear the way that he articulated into different melodies, the way he played around melodies and his sound was completely unique: If you hear Jaco, you say “That’s Jaco!” There are people that are very close, but you know when you hear Jaco. So, when I first started playing fretless with the Pat Metheny Group, it was very tricky because Jaco recorded “Bright Size Life” (1976), Pat’s first record and we were playing a lot of the songs from “Bright Size Life” as well as from “Watercolors” (1977) which was Eberhard Weber, so, for me I had to do it in my own way and I didn’t want to articulate like Jaco and I don’t.

Purposely, I just hear it in a different way but there are definitely threads of his influence when you hear my playing and there is no way of escaping it because of the nature of the instrument, the nature of how much I listen to Jaco, it’s a part of me. It’s a good part of me and I’m proud of it and I’m so grateful that I was around him in the early years because after I joined Pat Metheny and we were on the road, we would open up sometimes for Weather Report which was pretty spectacular (laughs) to be opening for Weather Report with the Pat Metheny Group and I noticed Jaco wasn’t the same, he was just abusing drinking and drugs. I said: “Oh man, that’s too bad” because he had bipolarism, I’m not sure what the diagnosis was, but it’s not good for that type of diagnosis to be taking drugs and everything. The nature of his personality was so Type A, he was always the king of whatever he did, and playing with Joe Zawinul (ed: Weather Report -keyboards), an incredible musician, I think he was very similar to Jaco, he was such a strong personality and they were always trying to outdo each other. So, I think it has something to do with that, but I can’t really say because I wasn’t around them and I didn’t know what was happening, I can only say that when I saw Jaco later, I was disappointed because I knew him when he was at his prime and he was the most incredible playing that I’ve ever heard, just incredible.

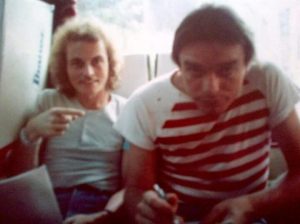

What’s the story behind the nice photo of you and Jaco Pastorius on the tour bus during the Japanese tour of The Gil Evans Orchestra in 1984?

When I was playing with Gil Evans, at the time, Adam Nussbaum was the drummer on that tour, and as I mentioned before, we played with Gil Evans at Sweet Basil club and also at Seventh Avenue South in New York and when Jaco was in town he would come in and we would play two bass players with Gil. I’d think Gil Evans got an offer to go to Japan that included Jaco as a special guest with me, so, we were two bass players. That picture that you are talking about was taken on the back of the bus in Japan going from Tokyo to Yomiuriland, which is outside of Tokyo, it’s a Disney Park-type of thing and there was a big stadium there and we played that night with Jaco. We were just in the back having fun and I was pointing to Jaco. He was great, we were having a great time and that was a spectacular tour touring with Jaco. He was kind of wild during that period: We would be on the way and he’d tell the bus driver to stop and he’d just go off and eventually he’d show up at the gig later on and we would play. It was great because we played some other songs, we played “The Chicken” (ed: from “Invitation” -1983), so we played: “PAM, pu-dun dun-dún/ pu-dun dun-dín/ dow”. We would play that in unison and in other songs I would play low and he would play high, sometimes we would both play the groove together or I would just stay out and let Jaco do his thing, which was crazy sometimes. It was spectacular and it was a really fun tour, that’s where that picture came from.

How much has your approach to bass changed over the years?

It’s funny because as a matter of fact, last night, for the first time in about 43 years, I played the tune “Jaco” that we played on the first “Pat Metheny Group” (1978) record. I played locally with a great guitar player Martin C. Hand, Howie Gordon (drums) and Rick Krive (keyboards) and we played at Art Museum for Gold Coast Jazz down here in Florida and Martin Hand, the bandleader, asked me if I want to play the tune “Jaco” and I said: “Wow! I haven’t played that in 40 years” since my days with Pat Metheny, so, I said: “Sure” and he asked me: “Would you mind talking about how the recording came about and all that?” So, I gave a little talk about how we formed the Pat Metheny Group like I spoke with you earlier and what it was like in the studio recording that song. I had to go back and listen to my playing and I’ve just played in so many different situations since the late ‘70s when we recorded that, and even before that, when I listen to my playing with David Sanborn. I hope I learned a lot, I’ve been practicing and studying the whole time, I think my approach bass-wise is more fluid, I have much more technique than I had then. I have much more theory about how to improvise over chord changes; more of a concept playing with so many great drummers and bands of the groove. My groove is stronger and I think I’ve develop -especially on fretless- my sound with the use of not only effects and just playing two different amps and my pre-amps and learning so much in the studio as a producer and an arranger since that time.

But like I said, it’s constantly changing, it’s constantly growing. The great guitar player Steve Khan (Steely Dan), he is doing a tribute to Ralph Towner, the great guitar player who recently passed away and it’s so interesting because he said: “I’m working on one of Ralph’s songs that I want you to play on and Mark Walker, the drummer”, who was the last drummer to play with Oregon (ed: Towner’s band). He did an arrangement of the song “Green Room”, that’s on the “Batik” (1978) record on ECM and it’s so interesting because when I heard Ralph had passed away, that’s the record I went to and I listened specifically to that song, the “Green Room” and he just sent me a track for it and all the files. He is in New York, I’m in Florida, so, he sent me the audio and I’m gonna play my bass parts over, but it’s a really honor to be a part of a project that is a tribute to Ralph Towner because I was a really big fan of him. It’s interesting how things changed. Now, I’ve been listening to a lot of Ralph Towner and I’m trying to learn more of the improvisational concept that he had playing over his compositions, which are in a lot ways very complex harmonically. There are a lot of different harmonic concepts in them. He was also a very-very well-accomplished piano player in the style of the great Bill Evans (Miles Davis) piano player, so, it’s great to be doing that and trying to grow with that. So, I’m constantly trying to keep it going.

I’m very proud of it. We worked really hard during the four years that I was in the band and doing those records. The fact that the music still holds up and it still sounds fresh in many ways, I ‘m so honored and so glad that I was a part of that flow of music and that the people still listen to it, I still hear people that listen to it and compliment and say: “That record got me into jazz” or “it introduced me to Pat Metheny and to many different types of music”. So, that shows how powerful music is. I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time and to know Pat and to have known Danny and Lyle and play in that group and to establish that sound. As I mentioned earlier, we worked very hard to have a band sound and every night after every concert, we had a band meeting and we talked about how was it or “we can do this better” and work on the dynamics. Someone sent me recently a list of all the venues, all the gigs we played over the four years; someone did a document of that, not only does it have where we played but it has the setlist and for many of the years it was the same setlist that we played, that same songs.

So, we constantly were trying to make them better adding sections to them, working on the dynamics, working on different songs, bringing new material. I’ve listened to some of those live recordings, how different sections had changed and we had added different things. So, it was constantly evolving and we were lucky to be able to be on ECM label and be recorded by Manfred Eicher who recorded that and Jan Erik (ed: Kongshaug) who was the engineer on the first record and to get the sound of the group right. So, it’s everything in the place at the right time with a tremendous amount of hard work like I said, travelling 300 days a year playing everywhere in the world, so, if you do it that much either it gets happening or it just falls apart and we made it happen. That record was a great documentation, because, as I said, we were playing for a lot of months in the States every night and we just went in the studio and basically we played our set down and that was the “Pat Metheny Group” record.

Is it frustrating that some people erroneously think that Jaco -not you- played on “Jaco” song from “Pat Metheny Group” (1978) album?

Well, that’s a compliment! Mark Egan played on “Jaco”, I can confirm it (laughs) ! If you listen to my playing on that, because the name of the song is “Jaco” I played Jaco-type lines on the very end (ed: he mimics the fast bass line) : “DAN/ du-dudú-pu-dut/ dan/ bu-búat/ don/ dudú-pu-dit/ grow-ap di-dikí-tit/ don”. I couldn’t help but play that, but for my solo, it doesn’t sound like Jaco at all to me. It sounds more like an upright player because I played it very melodically and I held the notes very long, it was a very melodic song, it was the first take. It was it! It was the only take! It wasn’t like punched in or anything. But again and we spoke of this earlier, Theo, that just because it’s the electric bass and also because it’s called “Jaco”, that people probably think it’s Jaco, but I’m flattered, I’m really flattered that they would think it was Jaco, but obviously he wasn’t in. If you go back and listen to “Bright Size Life” (1976) where Jaco played with Pat and Bob Moses (drums), it’s very different style.

“The Epic” was written by Lyle and Pat. It starts out: “PAA/ daa-daa-daa/ dáda” and then goes into a fast tempo, so it was well-titled being an epic, because it goes through different passages, different volumes and different chapters. It’s a ballad and then it goes up and “Ba-da-du-rí-tatá/ ba-daan” and it keeps getting faster and faster to get up to the tempo and then it’s a really fast samba. I can hear my influence by Stanley Clarke playing a fast: “DAN-du-dúku-tit/ dan digi-títin/ dun-dun”. I was very influenced by Stanley Clarke in the way he was playing samba with Airto, but it was a beautifully orchestrated piece, because Lyle Mays especially added so much orchestration to that to come up with different parts and Pat also, of course, because he co-wrote it. I remember it took a while to record that because there are so many stop and start sections, but we played it all the way through, it was a performance in the studio, it wasn’t cut in, and it developed really nicely; it tells a long story. I can see why they called it “The Epic”, but it was always great and very challenging to play, because I listen to it now and I think: “How did I remember all those parts?” We never read music on the bandstand, we always played music from our mind, we were never reading charts, ever. Ever, ever, ever, which is a lot of music to remember, but we were playing 3-hour sets every night, or 4 hours sometimes, if it was a two-show set, but the show was 2 hours and 45 minutes, that’s a lot of music for the audience to listen to (laughs).

Was it a bit weird to play on the records of Sting who is a bass player too?

It’s a good question, Theo. Again, we did a record with Gil Evans and Sting. Gil Evans was the band for Sting for the record “Nothing Like the Sun” (1987), there were two tracks that we recorded: One track was called “Up from the Skies” (ed: written by Jimi Hendrix) which isn’t on the actual disc but it was released as a single. It’s a great track, you can find recordings of it, it was released in Japan, I think. The track that was on the “Nothing Like the Sun” record was “Little Wing”. We first started playing with Sting when he would come to the club in New York called Sweet Basil, where we played every Monday night and many people came to sit it when they were coming to listen to us. So, Sting came and sat in and he played with us, he wasn’t playing bass, he was singing. We were playing “Up from the Skies” because that’s a song that Gil had arranged for “The Gil Evans Orchestra Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix” (1974) record, so, Sting knew the song and that was the song that he could come in and sit in at the club and one thing led to another and Sting asked Gil and the band to come and record in his record while he was recording at The Power Station in New York. That was the first or the second take in the studio: Hiram Bullock (guitar) was playing, Kenwood Dennard (drums) and all the horn players.

I knew that I would be playing bass on that but after that record came out we did a tour with Sting in Europe and we played in Perugia, Italy at the Perugia Jazz Festival; it was Sting and Gil Evans and we not only played that “Little Wing” song, but we played a lot of The Police songs. So, we were rehearsing to go and play with Sting in Italy after we recorded the record: We played “Roxanne” and “Tea in the Sahara” and I went up to Sting at the rehearsal and I said: “Sting, I’m assuming you want me to play your bass lines” and he said: “Mark, play whatever you want, I’m gonna be playing guitar and singing”. So, I said: “Ok”, but I ended up playing his bass lines because they were the hook. On “Roxanne”: “Du du du du/ Durú-dút” and “Tea in the Sahara”, it’s part of the composition. There would be little sections where there would be horn solos and we’d play around the horns, but if you listen to it, there is a record out, it’s called “Sting and Gil Evans – Last Session” and it’s the whole concert (ed: there is also a release called “Strange Fruit” but it includes songs from the Beograd concert as well) and we played with Sting. It wasn’t weird, I had to ask Sting: “Do you want me to play your bass lines?” So, even though he told me “don’t play my bass lines”, I did and I played them my way. It’s always different because he has a more muted style, I think my notes were a little longer, but it was amazing. It was an incredible experience. We played for 40.000 people outdoors at a stadium, so, I’m glad that was captured, you can find it, “Sting and Gil Evans – Last Session”.

Danny was still playing with Pat at the time and I had been writing my own compositions since the mid ‘70s. I talked to Danny and we wanted to do a record together, I had some songs that I had written and I had been recording at a studio called Howard Schwartz Recording which was in New York City, it was a great studio, they are not there anymore, with recording engineer Richard Brownstein, whom I had known from recording at that studio but he also went to the University of Miami, so, he know Danny and I and when we got together Rich said: “If you guys want to come into the studio, I can give you some studio time over the weekend” because it was mostly a commercial studio doing jingles and movies, they didn’t do a lot of records there. We could get free studio time if we go in the weekends but he had to go in starting Friday night and then record all day Saturday and then finish at Sunday night. Basically, we recorded two full days of recording and I had these songs and Danny and I got together about what we wanted to do. We didn’t have the name “Elements” yet, but we knew we wanted to record and we wanted to use Bill Evans, the great saxophone player that played with Miles Davis, we had been playing together a lot in a lot of sessions in New York and Clifford Carter (keyboards), who is a great friend of ours, who we knew him from the University of Miami. Clifford Carter and I moved to New York together with the Phyllis Hyman group with Hiram Bullock on guitar, Clifford Carter and Bill Bowker on drums.

So, Clifford and I go back to the University of Miami days. He is a fantastic keyboard player, he played with James Taylor, with Steve Jordan (The Rolling Stones, John Mayer) in the 24th Street Band, Will Lee and he’s just an amazing keyboard player, so, it was a perfect fit because we were doing sessions all together at that time: Danny, I, Clifford and Bill, so, we thought there would be the perfect match to do it and Danny and I were the leaders of it and they were the special guests, but when people hear of Elements, especially the original group they think of Mark, Danny, Clifford and Bill. So, we recorded that record and it came originally on the Philo Records, which is a small company up in Vermont and then we signed a deal with Antilles, which was a division of Island Records and we did two records for them: We did “Elements” (1982), the first record and then we did “Forward Motion” (1984) and then we got signed to RCA Novus group and we did four records on that label. So, we did a lot of recording and again we had been playing together with different groups, so, we had this unity as a group together and it gave us the chance to explore what we couldn’t explore with the Pat Metheny Group, in that we were now the leaders and we could come up with the compositions along with Clifford and Bill who contributed songs to the group. We are still together, I mean, Danny and I as a group, the most recent thing was the “Electric Blue” (2020) record, which I want you to show the cover of and I want you to show another record, it’s not Elements, it’s that record I did called “Dreaming Spirits” with the tabla player (ed: Arjun Bruggeman) and Shane, the guitar player, that plays on my recent “Cross Currents” (2017). So, anyway, that’s how Elements started and then we just kept evolving with that.

Not, at all. It actually opened up an outlet for me to release projects that I didn’t have with other labels. I recorded with GRP Records, I did a record called “A Touch of Light” (1988), I licensed that and all the Elements Records were licensed records, so, we were able to release them. The record on my label that was the first one to do was “Far East Volume 1” (1993), live in Japan, which is with Gil Goldstein on keyboards, David Mann playing saxophone, Danny Gottlieb and myself. We did “Far East Volume 1” (1993) and “Far East Volume 2” (1994), because they were two records. Then, we released a record called “Mosaic” (1985), which was originally licensed to a subsidiary of Windham Hill (ed: Hip Pocket) and that came on my record label since and I have 25 releases on Wavetone Records. You can find them at https://markegan.com/wavetone/ . You know, it was a lot of work to start a record company but it started slow, I just started with one release. I learned a lot about doing it and first of all, it’s all about coming up with a great product. You’ve got to have the concept, the sound, the production, the good pressings, at that time I was doing CD’s and I recently started to do vinyl releases. So, I came to a point where being signed to different labels, I didn’t want to be pressured or have people telling how I should record my records because I can only do what I know that I can do. I really felt strongly about starting a label, so, it was an experiment.

I started one at a time and it just gradually grew. For me, it was a stepping stone. I started out with a very good distribution company worldwide, I had another company that did all my warehousing and fulfillment, so, I established all that. I have a good business side to me; I’ve always been good at business, investing and finances, so, not only playing but in the ’80s and ‘90s I was very conscious of saving, not wasting money and put it in good places and not only investing in stock market, bonds and everything, but into myself and into this record company. So, Wavetone Records has been a labor of love: I haven’t made a lot of money, it’s pretty much paid for the next project that I put out. What can you do better than invest in your career? So, whenever I put something out, I always hired publicists and marketing people and the value of that is so strong because people have to hear about you. The beautiful thing about now is that we have social media, so, there are so many ways to get your music out there, it’s different than in the old days where you had a print magazine ad and you had to do ads wherever: On radio stations and all the different print media. So, there are many more tools available now to get things out, but at the same time there is a million more times competition because everybody is doing it, but I started early on, it was 1992 when I started Wavetone Records, so, I did it.

“Blue” Lou Marini (Blues Brothers, Eric Clapton, Levon Helm -saxophone) told me that he and Lew Soloff (Blood, Sweat & Tears -trumpet) were like mindreaders together: They would play the same thing right at the same time or they would be reading a part and every time that they’d play it, for 100 times in a row, they would play this note short and then suddenly one night they would both play the note wrong. Had you ever experienced the same with a musician you played together?

I have the same thing because I played with “Blue” Lou and Lew Soloff. I was in the band with them with Danny Gottlieb and Joe Beck (guitar), we travelled and we did quite a few tours in Europe and I experienced the same thing with them! I remember one night especially, it wasn’t with “Blue” Lou and Lew Soloff, but we were playing in Germany, the groove was in G, like a G7 and all of a sudden, Joe played an E triad, which if you are playing an E chord and a G in the bass it gives you a G-flat 9 and instead of me playing the G, I played an E at the same time and we looked at each other. I’ve had a lot of those experiences with Lou and Danny and many people that played together a lot of times. I love “Blue” Lou Marini and I miss Lew Soloff so much. Lew, “Blue” Lou and I played with Gil Evans for many-many years and we had a lot of those experiences, because when you have very good friends or family that you are really good friends with, sometimes you just talk and you say one word together and you know, you just know what the person is thinking, because your brainwaves and synapses are so in tune, that you think together and it’s just like that. It’s exactly the same thing, through the voice of your instrument, so it was like that with Lew and we had so great times with Lew Soloff and Lou Marini. We have so many stories, Lou have so many stories. He’s a fantastic musician.

That’s interesting: I hadn’t heard that but it doesn’t surprise me. I used to listen to Roland Kirk, there was a record called “Volunteered Slavery” (1969) and I listened to that record all the time. I think I can see how Jimi Hendrix would like the freedom of what Roland did and how loose it was, but yet it always had a groove and it always rocked in a jazz way, but in a groove way. That’s interesting that he would feel that energy because Roland Kirk gave out so much energy in his playing, he was playing with two horns, even if he was singing… and he was blind. I didn’t know that (ed: about Ronald Kirk’s influence on Hendrix), but thank you for that I can see how it could be that. I know that Jimi was influenced by a lot of blues players and he listened to everything.

Did you like Leland Sklar’s (James Taylor, Phil Collins) playing on Billy Cobham’s “Spectrum” (1973) album?

Oh, yes, yes! Leland is one of my favorites, his playing on the “Spectrum” record is fantastic, he is always one of those consummate players. I remember being in the studio in New York during a recording session in the other room and someone was recording on a James Taylor track, but Leland had already recorded his parts in LA, and I came in the control room and I listened and I assumed that it might have been Leland and engineer said: “Yes, that’s Leland” and I said: “It’s just perfect”. What he plays is just so right and so solid and he’s much more of a versatile player than people realize after playing on the “Spectrum” record and hear how he plays. He’s just a very-very well-rounded player that he always plays for the song and the song can be anything. He is a really versatile player and a master player who composes; the way that he writes his parts. Everything he did with Phil Collins, it’s always great. You never think about anything, you always just say: “It’s great” and there are very few players that play like that, it sounds like it was always there. It just should have been part of it and he plays so cleanly, he’s so even, he never overplays, he’s not a flashy player but he can play what sounds to be flash, but it’s what the song needed and it’s always spot on. He is a beautiful person, a beautiful man. Unfortunately, I’ve only seen him at the NAMM show in Anaheim, California. We’ve seen a couple of times but we are friends from there and he is a really nice person, a great person.

I agree with Ron Carter totally. Assuming everyone is familiar with the song, you know what the form is and everyone has done their homework to do it, and even if not, even if you are just improvising freely, the first take is what you really felt. To me, when you go into the second take, the third take, fourth take, fifth, whatever, you are always thinking of that and trying to change it and you are never really in the moment again, you are always in that moment (ed: the first take) and trying to make that better. It’s like a photograph: The first one is the photograph, the second one is you superimposing that and it’s a duplication of it and if you water it down, you have all the generations of the first thing. That’s one aspect of it and then another aspect of it, is that sometimes even your part was good on the first take maybe the leader of the band had a better take on other take and you are forced to do that. You say: “Well, ok, it’s good, but the first take was better”, even though that wasn’t on the record, that’s how you come up with re-releases of outtakes, because it was really good. Maybe someone else didn’t sound as good, you might have played well at that time.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Mark Egan for his time.

Official Mark Egan website: https://markegan.com/

Official Mark Egan Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/markeganbass