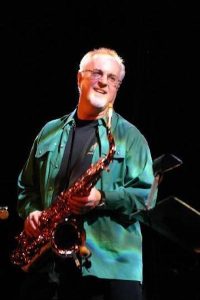

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: November 2025. We had the great honor to talk with a legendary saxophonist, arranger and 3-time Grammy winner: Tom Scott. He is most well-known as a founding member of L.A. Express and a member of The Blues Brothers. He has also collaborated with Steely Dan, Michael Jackson (he played the electronic wind instrument lyricon on “Billie Jean” from “Thriller” album in 1982), George Harrison, Paul McCartney & Wings, Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Jaco Pastorius, Al Jarreau, Tom Waits, Ravi Shankar, Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, Billy Preston, Nathan East and many others. In addition, since 2020, Tom is also a very successful podcast and radio producer. His latest solo release is “Live at the Bottom Line 1976”. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

(Laughs) Well, what’s not to love about that? Yes, I loved it, of course. I have arranged that tune before and actually these days I am doing a lot of what I refer to as “forensic arranging”, meaning take an existing arrangement from 30, 40, 60 years ago and modernize and update it. So, that’s what I did and it was Cynthia Erivo and everybody of course, and Quincy was such a dear friend to me and many people in the music business. He had a vision. He saw things in me that I didn’t even see in myself in the beginning. I can’t even begin to thank him enough for all he did in my career. So, for all of those reasons, plus I got to hang out with Herbie Hancock and Stevie Wonder. I mean, come on, how good is life when you are able to do that.

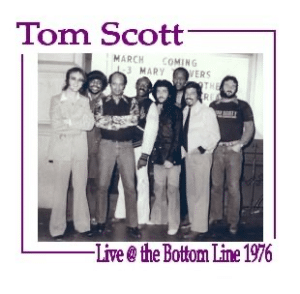

What’s the story behind the recording and release of your “Live at the Bottom Line 1976”?

I will tell you that that CD or download was recorded on a cassette machine, amazingly enough. My friend and former girlfriend, May Pang (ed: also former girlfriend of John Lennon and future wife of producer Tony Visconti), actually is the one who recorded it or had a copy of it, I don’t remember exactly, but she loaned it to me and I put it up on iTunes. I said this on the stage at the Bottom Line, when this was recorded, more than once: “I’m just happy to be standing on the stage with these other people, ok? It’s a privilege”. That rhythm section, of course, was Chuck Rainey (ed: Aretha Franklin, Steely Dan -bass), Steve Gadd (ed: Eric Clapton, Steely Dan -drums), Eric Gale (ed: George Benson, Quincy Jones -guitar), Ralph McDonald (ed: Roberta Flack, George Benson -percussion), Richard Tee (George Benson, Grover Washington Jr. -piano), Hugh McCracken (ed: Steely Dan, John Lennon -guitar). They were and remain in my mind the best rhythm section ever and there are very specific reasons for that: First of all, they were all stunningly talented, great musicians, but the way they worked as a group; they created parts like it was a jigsaw puzzle perfectly fit together. The two guitars for example, you had Eric Gale doing his fast strumming (ed: he mimics the sound) “Djagt-djagt/ djigt-it/djik djigt-at” and Hugh McCracken going (ed: slower) “Dàao dou daaaà” (laughs). And of course, Richard Tee, what he taught me about piano playing and accompaniment. Let’s put it this way: These people I just mentioned had doctor degrees in accompaniment and they elevated it to a high art and people don’t appreciate that so much, but believe me, it’s a rare talent that people have, to know what to play that just fits the tune exactly right. Boy, nobody, has ever been any better at that than that group right there.

How did you come up with the idea to start doing podcasts?

How did you come up with the idea to start doing podcasts?

Oh, that’s easy! Covid was the answer to that. I, like everyone else had to shut down my operations, my career, in a way and I said: “What I’m gonna do?” I had met a delightful person who’s been my podcast and radio show producer since then, a guy called Joe Vella, he lives in Connecticut, on the other side of the United States, in East Coast and he turned out to be just a wonderful associate to create podcasts and encouraged me to do it along with another guy, Dr. Dave Schroeder, who at the time was the head of the Jazz Department at New York University. So, the three of us came up with the idea: “Tom, you’ve got a good radio voice, why don’t you interview some of those people you know?” and I thought: “Yeah, why not?” So, lo and behold, I found out that I really enjoyed not only the podcast itself, but doing the research. I always loved to come to an interview, like you, I’m guessing, you’ve done your homework, you know exactly what you want to ask, but by the same token if the subject drifts off into another area, you are perfectly willing to go there if the guest wants to do that.

I’ve probably done 60 interviews and I’ve always had a great time interviewing rocket scientists, the head of Jeff Bezos rocket company, Blue Origin, (ed: Steve Squyres) who is a friend; people like H.R. McMaster, who was former head of National Security for Trump many years ago, but a fantastic guy, and actors and actresses: Anjelica Huston, Malcolm McDowell (ed: “Clockwork Orange” -1971), Billy Bob Thornton and of course a lot of musicians. I ‘ve had so much fun talking to these people and also learning about their history. You know what, the one theme that exists throughout all of these interviews is everyone at some point in their lives -usually early, in their teens or whatever- they had someone in their life who encouraged them and said: “You have value, you can do this thing you wanna do, without fail, 100%” and it makes you wonder of all the people who could be famous today for something, they are not because no one ever encouraged them to do so, to explore their talents and showed them that “I have confidence in you, that you can do this”. I found that to be a very valuable lesson. We all need support from someone in order to be our best selves.

What are the projects that you are currently involved with?

Let’s see, what I am doing? I have a gig playing with a Steely Dan cover band (ed: The Music of Steely Dan) based in San Diego, which is in Southern California, I’m in the Los Angeles area, and they have recruited some of the Steely Dan members, along with myself, people who have played (ed: with Steely Dan), it’s an ongoing thing: Jeff “Skunk” Baxter (guitar) has played, Denny Dias (guitar), Keith Carlock (drums) who was not in any of the records but he has toured with Steely Dan a great deal. Who else? Those are the main ones that I can think of and then they added vocalists and other people to fill it in. We just did a gig down in San Diego, on Sunday, two days ago and it’s always great fun to do that. Plus I have reconstituted, you could say, the L.A. Express, which of course in the ‘70s, 1973-’74, was a band that I created at a club called The Baked Potato in North Hollywood, California. At that time the band was a couple of people that you may have heard of: Joe Sample (The Crusaders -keyboards), Larry Carlton (Steely Dan, Joni Mitchell -guitar), Max Bennett (Peggy Lee, Joni Mitchell) and John Guerin (The Beach Boys, Peggy Lee) on bass and drums.

Actually, we were on TikTok first, we are still on TikTok for that matter, but in those days you can only do 15 seconds of an existing record. So, I would take tunes that I’ve soloed like Paul McCartney’s “Listen to What the Man Said” (1975), for example, and I’d put the audio on my computer and go up to this solo and then I hit the button, play it back, I run over the green screen with my soprano (ed: saxophone) and pretend to re-play the solo that I played on the record. Then, I would take that audio and that video and send it to Joe Vella in Connecticut and we would put that record (ed: the album cover) -in that case “Venus & Mars” from Paul McCartney & Wings (1975) – behind me, as I’m playing the soprano sax. Then, I would do a companion video, where I say: “Look, in 1975 I got a call from a sound engineer at a studio in Hollywood and he said: ‘I’ve got Paul McCartney here at the studio and he asked if you could come and play the soprano sax on one of his tunes’ and I’ve said: ‘Sure. When does he need me?’ He said: ‘What are you doing right now?’ and I said: ‘I guess, I’m on my way to Hollywood to a recording studio to play with Paul McCartney’”. Stuff like that. People love those stories. In fact, the parts where I explain what I did, get more views than me playing (laughs), which is fine. I get it, people are fascinated by “what was it like with Paul McCartney or Carole King, George Harrison, Joni Mitchell, whoever”.

Please tell us everything we should know about your solo in “Black Cow” from Steely Dan’s “Aja” (1976) album?

Well, the solo I did on “Black Cow” was just a very small part of four nights of recording, in which I wrote all the horn arrangements for “Aja”; the only one that I wasn’t involved in was the tune “Aja” itself, which has that marvelous Wayne Shorter (Miles Davis, Weather Report) sax solo, that was done. But they wanted horns on the rest of the tunes, so, they gave me a tape of the tracks, I took them home and wrote out horn sections. We had two trumpets, two trombones, four saxes, something like that, I think it was 8 horns. You are probably aware of this: The Steely Dan had a reputation for being very picky and doing things over and over again, with great musicians every time, but something wasn’t right in their view. I never understood it myself, but whatever, that’s fine, the records speak for themselves. So, I went into the studio thinking: “Ok, well, gosh, I hope I don’t get kicked out on the first night”. Lo and behold, they recorded everything, every arrangement that I wrote as it was. The thing about “Black Cow” was, I had written a horn phrase to be played over and over during the fade, which went: “Daaà-da daaà-da/ Di-diii da-dài-o-da/ Tirí ti tití”. So, we played that a few times and either Walter (ed: Becker -bass, guitar, vocals) or Donald (ed: Fagen -keyboards, vocals) stopped and said: “Tom, why don’t you play that lick once and then do a solo for four bars and then do the lick again and then you solo for another four bars”. I said: “Ok, great”. So, I think I did probably one, maybe two takes at most. That was it.

It’s very rare for a Steely Dan record because Randy Brecker (Brecker Brothers, Blood Sweat & Tears, Bruce Springsteen -trumpet) told me that everybody who went into a Steely Dan session, knew that they would play 20 or 30 takes, so they saved the best lines for the end.

It’s very rare for a Steely Dan record because Randy Brecker (Brecker Brothers, Blood Sweat & Tears, Bruce Springsteen -trumpet) told me that everybody who went into a Steely Dan session, knew that they would play 20 or 30 takes, so they saved the best lines for the end.

(Laughs) Of course, that’s funny, but that’s not the way it works. You try to give your best performance on take 1 and that’s why it gets frustrating to do many takes. I mean, this didn’t happen to me (ed: on a Steely Dan session), it’s happened with other people, not Steely Dan. It happened with Michael Masser, a producer/songwriter guy (ed: Whitney Houston, George Benson), very successful. He called me one day and he said: “I have a new singer that I’m recording on Arista Records. Her name is Whitney Houston and I tell you she’s gonna be a big star” and I said: “Ok, well, great. What do you need?” “Well, there is this tune that I like you to play on”, “Ok, great”. So, I showed up in the studio, Michael Masser was there and the sound engineer. Whitney Houston had already sung her vocals, so, I didn’t get to meet her, at that point. The tune reminded me a kind of doo-wop ‘50s vibe: “Dooo/ (ed: he snaps his fingers) doo-doo-doo/ Doo-dàn/ Dii-dan/ Dàra dàra”, that kind of feel, you know and it turned out to be “Saving All My Love for You” (ed: from “Whitney Houston” -1985) of course and he asked to play whatever I felt, over and over. “That’s great! Give me one more!”, “that’s great! Give me one more!”, “that’s great! Give me one more!” So, right around take 17 or 18, I put my horn down and I said: “Michael, I have played every possible phrase and piece of music, that would fit in your tune. I know it’s there, somewhere. They all are there somewhere, I don’t have anything more that I can add to it, honestly. So, I would suggest you to go back to maybe take 2 or 3, do whatever you want, I am out of here” (laughs).

But then when the record went out, the producer Michael Masser called you to thank you about your contribution.

No, no. That hasn’t happened at all. No. Whitney Houston called me.

Sorry, I was confused (I read about this a long time ago).

That’s ok. The phone rang, I picked it up, “Is this Tom Scott?”, “Yes”. “You don’t know me but my name is Whitney Houston. You played on my record”. I said: “Oh yeah, right. Hi”. I had never seen her, I didn’t know anything about her except that I played on her record. She said: “I just want to tell you how much I appreciated your work on ‘Saving All My Love for You’”. I said: “That’s very sweet of you, thank you very much”. You know something, I tell that story whenever the subject of Whitney Houston and her untimely dead and all the tragedy that came later, comes up. I tell the story, because in order for her to make that phone call, she had to call Michael Masser, ask for my number, pick up the phone and call me. She took the time to do that and I thought that was so sweet of her. Clearly, she had a very sweet side to her.

You were responsible for the horn arrangements on Steely Dan’s “Aja” album. Are you proud of your contribution in this classic album?

You were responsible for the horn arrangements on Steely Dan’s “Aja” album. Are you proud of your contribution in this classic album?

Well, all I can tell you is results are the most important and the result of that album, it is considered a classic. In fact, there are people who list it as perhaps the greatest pop/rock music album ever made and I tend to agree with them. Not just because of my arrangements, but my arrangements clearly were part of it. Am I proud of it? You are damn right, I am. Very proud. It was delightful that our paths crossed. It was actually Walter Becker and me that we knew each other and one day he says to me: “Hey you, you write horn arrangements, don’t you?” and I said: “Yeah”. “Well, we are doing this album and we want to write some arrangements for us”, “Sure”. That’s how it started (laughs). As simple as that. Of course, I am proud. Absolutely. It’s a wonderful record and we keep playing this stuff over and over with this Steely Dan band I’m in. We are revisiting that album every time we do a concert.

I really like “Glamour Profession” from Steely Dan’s “Gaucho” (1980) album. Did you have a good time playing the alto saxophone parts along with Michael Brecker (Brecker Brothers, Joni Mitchell, Bruce Springsteen) on this?

Listen, Michael Brecker was a dear-dear friend and a saxophone god may I say (laughs). I loved him. We were dear friends. I so admired his talent because he was much more of a technical wizard and he would play explorations that just weren’t in my wheelhouse, I’m more of a melody guy. That’s the way I was born, I guess. My father was a composer, maybe that has something to do with it. When you are in the studio working at that kind of professional level, it’s always a joy (laughs). Always. It’s great fun and with a guy like Michael Brecker sitting next to me, I know we are gonna be in lockstep with whatever the tune needs. So, that makes it so much more fun.

You became a Blues Brother by accident replacing Tom Malone (trombone). Could you please share this story with us?

What happened was this:, I only knew The Blues Brothers from the one time I had seen them perform on Saturday Night Live. I don’t think they were called The Blues Brothers yet, it was just a skit with Jon Belushi and Dan Aykroyd and the band that they had assembled. It’s so funny, because comedians so often want to be musicians and musicians so often want to be comedians. It’s a funny thing, whatever that is. But in any case, I had seen that video and I was opening the paper one day and they were coming to Universal Amphitheatre, which in those days, in 1978, it was an open air coliseum kind of thing. I read that Steve Martin, who at the time was the most popular stand-up comic in America was going to be for the week and his opening act was The Blues Brothers and I thought: “Oh, my God!” I knew two of the horn players Tom Malone (trombone, saxophone) and Lou Marini (saxophone) and I thought maybe they can get me backstage and I just liked to hang out with them and maybe meet three of the hottest comics in America, that would be fun. So, as it turns out about two weeks before that concert begin, I got a call from Tom Malone. He said: “Tom, listen, my wife is set to have a C-section to deliver our new baby, right in the middle of that week where we are playing with Steve Martin and The Blues Brothers. Can you sub for me until I get there?” I said: “I think I can do that. Yeah, I think that’s highly possible”.

The other story I have to tell you about that is how I got the name Tom “Triple Scale” Scott. It was the day that my tour manager came, Jim Root, is his name, he was tour manager for Cheech & Chong, just a great guy and a pal, you know. I said: “Look, nobody has talked about money and I don’t want to ask the other guys in the band what they are making because God only knows, they can have different deals, that’s not the point. All that matters is what they plan on paying me”. So, I didn’t want to bring it up, so I said: “Jim, can you come along with me and just if there is a moment where the three of us” -John, Jim and me- “are alone, maybe you can pop the question at that point”. So, that moment arrives and there is Jim standing next to me and John is in front of us and Jim says: “By the way, what are you planning on paying Tom for this week at the Amphitheatre? You know, he usually gets triple scale”. That means, triple union scale, whatever union scale is for any player that is a union member, I make three times that and that wasn’t always true, ok (laughs). But you know that old saying: “Negotiate from strength”. I don’t remember what it came out of the discussion about money, what I do remember is that Belushi’s response to that triple scale thing was: “Oh, really, does he?” So, from that night on he called me Tom “Triple Scale” Scott.

Does “Briefcase Full of Blues” (1978) capture the true spirit of a Blues Brothers concert?

That is true, sir. That’s right. I don’t know, I wasn’t involved in the production, I don’t know if they taped every night, but I know they taped at least the last two or three nights and I’m sure they called together the best performances. They were all good performances, so, it couldn’t be too hard to pick good takes of all those tunes that were on there. As I say, I had a ball, it was great fun.

Was John Belushi (Blues Brothers -vocals) an easy-going person to work with?

John was two people. He was exactly that person you just described: Easy-going, lovely, fraternal. He was younger than us and he said: “Tom, listen, if you have any problem, you just come to your Uncle John”, “Ok”. He had a side that was very-very sweet. The problem was that sometimes he tended to alter his state from time to time, if you know what I mean by that, how you alter your state of mind.

He had some addictions.

Yes, that’s right and sometimes -I don’t know if I had ever witnessed this, but I certainly heard about it- if things didn’t go his way, for example, I will tell you: The night that he tragically overdosed, he had been at a meeting at Paramount that day with his writer pal, Mitch Glazer, the two of them had written a script that they wanted Paramount to make it into a movie. I wasn’t there but as I understand, they had that meeting with the executive, whoever it was, I don’t know, to discuss the making of this movie and the executive turned them down and John went into a rage and I’m sure he enhanced that rage with narcotics of some kind, and that’s the guy that I’ve heard about. Dan Aykroyd described it in a letter to me once. They were very much like brothers, they were very tight friends, as tight as any two friends could be. Danny described this two-sided thing of him: “When he was in the narcotic area he had two moods: Either trance, like he is in a trance, or venom, like a poisonous snake”. I thought that was very poetic actually, to describe the guy’s moods when he wasn’t sober and just regular ol’ John. He was a good guy in his heart. He was a good guy, really. I liked him.

Were you frustrated that you didn’t play in “The Blues Brothers” (1980) film?

Well, no, I am not frustrated because I had reasons not to be in the movie. Would it have been nice to be in “The Blues Brothers” movie? Sure. By the way, that scene with “Blue” Lou Marini where he is washing dishes, in the restaurant with Aretha Franklin and all that, that scene was written for me originally. I was happy for Lou, he did a great job doing it, but I decided not to be in the movie because, I, unlike a lot of the people in the Blues Brothers band, I had been very familiar with the movie and television industry because I have written television and film music since the age of 20, actually, that’s when I first started. I was familiar with what it meant to be a supporting cast member on a movie that could take 6 to 9 months to shoot. What it means this, is that you will be sitting in a trailer for hours and hours and hours on in, waiting to be called and you would be called for 6:00 in the morning or 2:00am or any time in between. I had other things going, I had other projects. As I say, I was writing music for television, dramatic music for cop shows and stuff like that and I just thought that that’s too long for me to be out of my other areas of work. So, I turned them down. John Landis, the director, called me, he was just furious. (Ed: He shouts) “How could you turn this opportunity down?! What’s wrong with you?!”, “John, you will figure it out ok without me. I appreciate your enthusiasm but the answer is still ‘no’” (laughs).

Was Ravi Shankar’s “Shankar Family & Friends” (1974) album a catalyst to your later collaboration with George Harrison?

Absolutely, it was the reason that I met George Harrison. I got called to be on the album “Shankar Family & Friends” because that was George Harrison’s first production for his brand new record label called Dark Horse, which was on A&M. A&M Records in those days occupied a lot of what it formerly was Charlie Chaplin’s film studio and it obviously went through some evolution, but became A&M recording studio, business office, publishing house, all in one. It was a fantastic place. You walked into it and there were four studios: A big one, a medium-sized, an overdub room, a mixing room and all that. I worked there a lot. I was doing a lot of freelance recording. So, you could walk in there and see maybe Billy Preston (ed: The Beatles, George Harrison, keyboards) doing his solo albums. In fact, I played on “Will It Go Around in Circles” (ed: from Billy Preston’s “Music Is My Life” -1972) “taaá-rat/ di-ri-diii-dit”, that’s me (laughs) on the horn section on Billy Preston. Then, you could have Joni Mitchell or Carole King or The Carpenters or Captain & Tenille, an endless list of A-list recording artists in there, recording. So, it was just like “How cool is this?” to even be on the lot, let alone to actually participate in some of those things. The Carpenters, one of the things that I played on was a little thing called “Sing” (ed: from “Now & Then” -1973). It starts out with a soprano recorder going “Ta/ ta-ra-tatá/ Tatá tara-tatá/ tatá tara-taTAAAA”, that was me (laughs).

Could you please describe to us your friendship and collaboration with George Harrison?

I was there because I had studied Indian music with a gentleman named Harihar Rao, who was on the record and he was an ethnomusicology professor at UCLA, who I had met. He was from Calcutta, India. When he was there he studied with… drum-roll… Ravi Shankar. So, when Ravi was asked by George Harrison to come and do a record with some Indian musicians and some Western, American musicians, he called his friend Harihar and said: “I need some musicians who have some kind of knowledge of Indian music” and I’m on the list, so, I got the call. So, the first day it was again A&M Studios with this mixture of marvelous Indian musicians and Americans and I’m looking on the booth, I forget who was sitting next to me but whoever was I said: “That’s George Harrison in there, oh my God! It’s a Beatle, oh my God!” like anybody, I was as captivated by his presence as anybody who doesn’t know him. I mean, he is a Beatle, for God’s sake. I don’t think people these days know what The Beatles meant; they were musical icons and cultural icons of a degree that there is nobody like that. Well, Taylor Swift maybe, I don’t know but it’s not the same. It’s just not the same.

We don’t know if this music will stand 50 years later.

Yeah. Yeah, questionable. I wish her well but I don’t know. So, it was so cool: “God, there he is, in the booth and I’m recording a record and he is producing it. Great”. We got to the first break. He must have seen something in me or somebody told him something, I don’t know why, but when you were on the break most of the people went out of the room to get coffee, you know, a 10-minute break. I just stayed in the room, I don’t know why, I just didn’t feel like getting up. He walks out of the booth, he comes into the studio, comes right up to me and says: “You are the one who studied with Harihar Rao”, I said: “Yes”. He said: “Do you like Indian music?” I said: “Yeah”. He said: “Come with me” and so, at that moment, I become I would say one of George’s closest friends for about three years.

I’ve seen a photo of George Harrison wearing a t-shirt of your “New York Connection” (1975) album. It seems that he was very supportive to you, wasn’t he?

I can’t begin to tell you what a friend he was. He was just a delightful, warm, lovely, funny, witty human being. Smart and just a delight, what can I say? I love the guy. I miss him today, even today I miss him.

How emotional was it for you to play at “Concert for George” at the Royal Albert Hall in London in 2002?

It was very touching, plus very intelligently the concert featured the things and the kind of music that George loved best: Monty Python were on the second part of it. Ravi Shankar’s daughter, Anoushka, conducted all Indian orchestra, the first part. Then, the third part of course was a rock concert with the music director Eric Clapton which featured a lot of rock icons, shall we say, including Paul McCartney and Ringo and George’s son, Dhani, who was a little bit of a blend -in his looks- of George and Olivia (ed: George’s wife). From certain angles, I said: “Oh my God, has George Harrison returned from the dead?!” (laughs) Anyway, it was very touching because the guy was so loved by those who knew him. You had no trouble recruiting people to do a memorial concert for George because he was just so warm and wonderful as a human being. And talented, by the way!

How much has your approach to saxophone changed over the years?

How much has your approach to saxophone changed over the years?

I don’t have a master plan how I am gonna evolve the saxophone, it just happens over time. I think, if I were to answer the question as best as I can, I would say that I matured a great deal and by that I mean, I probably have a better sense of what to play, what it works. I used to a be a kind of show-off, you know, playing a lot of notes sometimes; not as many as Michael Brecker (laughs), but I’ve learned that very valuable lesson which some people know instinctively and some people take a little longer to learn which is “less is more”. Play less but have meaning. George Harrison was a natural for that! George said to me one day -I swear this happened: “You know, I’m an OK guitar player but I’m not really great or anything. I’m not like my friend Eric Clapton”. I’m sure by that he meant Eric Clapton has a lot more blazing technique and all those licks he plays; George tended to play simpler, but I said to him: “George, let me tell you something: First of all, a guitar exists of a piece of wood with some strings stretched across it, right? So, anybody who can actually have an individual sound is by my definition uniquely talented. You, my friend, are one of those people. Personally, you put that slide of your finger and then start doing this, we know who it is exactly because that’s your talent, your gift. You are a very gifted guitar player. You can put yourself wherever you want but your argument is falling on deaf ears, as far as I’m concerned (laughs). I think you are a marvelous guitar player because for whatever you are lacking and what you think of this: technique, you make up for this, with your very tasteful playing”.

Were you surprised when Wings’s “Listen to What the Man Said” (from “Venus & Mars” -1975) became a #1 hit?

I’m always surprised by anything that I played on that becomes a hit. I’m always surprised and delighted. I learned a long time ago that I have no ability to guess what is gonna be a hit or what isn’t. I guessed one time; the one time I said this is gonna be a hit, I was actually at George’s house in Los Angeles here visiting and he says: “My friend Gary Wright is coming over”. I said: “I’ve heard of him. He is a piano player and singer and recording artist. Oh great”. So, he came, a very nice guy, he puts his record on, it’s “Dream Weaver” (1975). He plays this tune that I had never heard before and I said: “Ok, if that isn’t a hit, I’m gonna quit the business!” (laughs) Thank God, I didn’t have to quit the business. Look, I’m always delighted when things that I play on, go #1 or #10 or #15, anywhere that means that people are listening to it. That’s what is important to me: A number of people listening to it, because that means that we’ve done a good job. If it’s popular, that’s why we are there for. We are not making records for our musical enjoyment, although we enjoy doing it, don’t get me wrong, but the point is to make music that is accessible to the public.

Well, as always, I got a call from Quincy, my dear friend Quincy Jones and he said to me: “Tom, we need you over here to do some finishing touches”. They used sometimes the term that was floating around, “ear candy”, meaning little parts of the tune, maybe not the whole tune, but little flashes of ornamentation that add to the excitement and enjoyment of the song. So, I show up at Westlake Studios, I think, on Beverly Blvd. in Los Angeles, I meet Michael Jackson for about 10 seconds. He comes in, he says “hi”, he is in his military garb, I shake his hand and he had -if you ‘ll pardon my saying this- a limp handshake, like very weak and he had this ethereal aura, I thought if I just took a big breath of air and went (ed: he blows) “ffoo”, we would probably float up and down in the ground. I mean, he had that lighter than air vibe to him, I don’t know how else to describe it. Of course, he didn’t float away, I didn’t blow on him and everything was fine, but then he left. As far as making the record, he was gone. So, I went into this booth where Quincy was and he said: “Tom, we have these few little things that we want you to play on the lyricon”. I already played the lyricon for him on “Sounds… and Stuff Like That!!” (1978), which is one of Quincy’s albums, so, he knew about the instrument. They played me this thing and I have two contributions to “Billie Jean”. I will sing the chorus until I get to my part: “Billie Jean is not my lover/ She’s just a girl who claims that I am the one/ But the kid is not my son/ Tou-TIÍ-ra/ TA-TÀ-ra”. That was me. (laughs). The other part is (ed: he snaps his fingers: “Bo…bo/Tu tun tùn/ tu… tataTAAAÀ-Dara-rlaà/ Tata-TAAÀ/ Daa-arlaàt”. Those two licks; I was out of there in 45 minutes.

Do you any memories from the recording of “Theme from Taxi Driver” from “Taxi Driver” (1976) film?

Yes, sure. First of all, I have to make this distinction because I insist on doing it, because there is the mistaken notion, even from the director Martin Scorsese himself who had said this in speeches and concerts that they have done with music from his movies, that I played on the movie. I did not play on the movie. A wonderful saxophone player, a studio player for years named Ronnie Lang, he is the one that played in the movie. So, the movie came out, it was such a success that they decided to do a “pop” version of Bernard Hermann’s theme from “Taxi Driver”. So, not knowing any of that, the phone rings one day: “Hi, we have a session for you on Wednesday at RCA at 2:00pm. Bring your alto saxophone”, “Ok, great”. Boom. Wednesday comes, I go to RCA, I walk in the room -RCA Studios in no longer there but it was a very large room that could easily house a symphony orchestra, it was that big, a big-big room- and I see there is a string section set up and a rhythm section set up and a podium where the leader is gonna sit and conduct and there is a single chair in the middle of the room and that was for me. It was the alto sax part that I played on the “pop” record version of the “Theme From Taxi Driver” and it became an iconic thing. It’s on the soundtrack. And part of confusion is the fact is that of all the people that played on that session, I was the only one who had a recording contract with another label, I was on Ode Records, at that point, Lou Adler’s (ed: The Mamas and the Papas, Carole King producer) label, so, they were legally obligated to put my name “Tom Scott appears courtesy of Ode Records”. So, that’s what fostered the whole idea: “Oh, he must have played saxophone on everything” (laughs). They didn’t have to list Ronnie Lang because he wasn’t a recording artist on a label, but they had to list me.

Was it an interesting experience to record “Terminal Frost” and “The Dogs of War” from Pink Floyd’s “A Momentary Lapse of Reason” (1987)?

Was it an interesting experience to record “Terminal Frost” and “The Dogs of War” from Pink Floyd’s “A Momentary Lapse of Reason” (1987)?

Sure. I never thought in my life I would play on a Pink Floyd record, but the producer Bob Ezrin, nice guy, I liked him a lot, he called me and he said: “We’ve got this thing for you to play on”. None of the members of the band were there, it was just him and me and I played whatever I played, I don’t remember any more, it’s been too long, maybe I did a podcast on it, I can’t remember now. Yeah, it was a session, I played. Fortunately, because I have played with a lot of very famous groups, some of these things become kind of iconic and I’m delighted at that, but I was just part of the system that contributed to the success of these records. If I had anything to do with the success of the record, lucky me (laughs). I’m so lucky to ‘ve been a part of it but I don’t say: “Yeah, it was because of me”. I’m smarter than that. But I helped.

How important is improvisation for you?

I can’t even begin to calculate. Improvisation is ¾ of my life. I mean, I started out as a devotee of Cannonball Adderley (saxophone), John Coltrane (saxophone), the real heavy jazz guys of the ’50 and ‘60s and I actually got to play with one of my other heroes, Gerry Mulligan, the great baritone sax player, arranger and bandleader on one of his records. So, jazz was my go-to. I thought I was gonna be a jazz musician, then, I started working in the studios and it’s great to get paid for doing what you love. “I’m gonna get this right. I’m gonna play the saxophone, the clarinet or the flute and you are gonna pay me money, right? Is that the deal? I’m in!” (laughs) So, improvisation was part of it because a lot times people would say we have a 8-bar thing here, opening for a solo and they are not gonna tell me what to play, ever. They say: “Give us some options”. So, I listen to it, I think it over and then I go to the studio and I give them two or three or four or eighteen or whatever it is, takes and they are all me. It’s all improvised. Without improvisation I wouldn’t have had the career that I had.

Is there any interesting story from the sessions of “Estimated Prophet” from Grateful Dead’s “Terrapin Station” (1977) album?

That was a session again that members of the band weren’t there. This was a producer named Keith Olsen (ed: Whitesnake, Ozzy Osbourne, Foreigner). He was very-very-very good, I really admired his production technique. Very-very good. Again, another session, I went in, played whatever they asked me to. I think that’s the one that’s in 7/4 time. I just did, I played a few takes, went home, got paid (laughs).

(Laughs) Oh, jeez! It was remarkable. So, when I went on the George Harrison tour in 1974, the tour producer was Bill Graham (ed: legendary promoter and owner of Winterland, Fillmore East and Fillmore West), so, I got to know Bill very well. I am going back a little bit now, if you can let me indulge me. When we were rehearsing the George Harrison show, we were at A&M, there was a big rehearsal hall there, we rehearsed there for a couple of weeks and in the meantime Bill, of course, was preparing the production for all these cities and we were playing all the big-big arenas in every city, you know, basketball courts and God knows what. He was busy doing his thing in another room, but at one point George approached me and he said: “Tom, listen, I wanna ask you a favor”. “What is George? Whatever you want, man, I’m at your service”. He said: “Bill Graham wants to talk to me about the concert and I don’t want to talk to him. Will you go and find out what he wants and then come back and tell me?”, “Sure, why not?”

I go to Bill Graham’s office and I say -how often are you gonna hear this: “George Harrison sent me (laughs)”. He says: “Yeah”. “So, whatever you are gonna say to me, he wants me to relay that message back to him”. He says: “Ok. Well, I’ll tell you, we are gonna clean in 45 cities”, meaning “sold out”; every city that we were gonna play in the upcoming tour has already sold out. I said: “Man, that’s fantastic”. “But here’s the thing”, he says, “all the feedback I’m getting regarding this upcoming concert is ‘we want more Beatles songs. In fact more than anything we’d like to end up being a Beatles reunion if that’s possible’”. I said: “Well, I’m not so sure about that but I will relay the message about more Beatles songs”, because at that time I think we didn’t play other than George’s own songs that he did as a Beatle like “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”, “Here Comes the Sun” and “Something”. He used to say: “Something in the way remove it” (laughs). Then, the only one we were doing was “In My Life”, which is a Lennon song. We did that one on the tour. That was the only one, the only Beatles song other that George’s own. So, I go back to George and I relay the message and George says to me: “Tom, I used to be a Beatle, I’m not a Beatle anymore, I don’t wanna revisit The Beatles, I wanna move on with my life and do what I’d like to do on this concert. Maybe you should go back and tell Bill Graham that if anybody is unhappy with that, they can have their money back”. “Ok, I will tell him”.

So, I went back to tell Bill and he was like (ed: grumpy) : “Oh, God! Alright, alright. We’ll go with it”. And in all the promotional posters George wasn’t dressed as a Beatle, of course, he was dressed in the Indian white linen outfit and he (ed: Bill Graham) said: “Oh God, what is this?!” Anyway, I wanted to say that because Bill Graham of course was the guy who was the producer of the Winterland concert and at one point he came down from the ceiling on a rocket ship that was on a cable. He rocked it down to celebrate the coming of the New Year. It was a tradition apparently. I loved Billy Graham, by the way. I loved him and I completely understood his point of view: He was just trying to do what’s best for the artist in his way”. It doesn’t mean that the artist is gonna do it. So, we did our Blues Brothers thing and then there was a party, I think it was at Grace Slick’s (ed: Jefferson Airplane -vocals) house or something like that and they all said to us: “Listen, don’t drink anything, very likely it has been laced with LSD or something”. Well, John (ed: Belushi) drunk something and sure enough he got high as a kite and had to be taken back to his bed, I think, carried back to his bed, as I recall. But it was fun. It was so iconic: A bunch of screaming San Francisco fans in Winterland, come on, it’s very surreal, it’s like a dream. A lot of that stuff was like a dream, you know, but it happened.

What do the 3 Grammy Awards mean to you?

What do the 3 Grammy Awards mean to you?

(Laughs) I’m honored that my fellow musicians, fellow people in the recording business choose to honor me that way. One of the first of course was for “Best Arrangement Accompanying a Vocalist” for Joni Mitchell (ed: for “Down to You” from “Court and Spark” -1974) and I shared the award with her, although I think unfairly, because I don’t think Joni understood what the difference is between a composer and arranger, because I was the arranger. I took her piano part, her music, while she is the composer, 100%, I took that music and extracted parts of it for an orchestra and enhanced it with an orchestral accompaniment. That is the arrangement, she had no part in this. I walked into the studio with the orchestra, she had never heard it before, she hadn’t participated in it, nothing. I resented it for years, but suddenly it occurred to me, not that long ago: Maybe she never understood the real difference because a lot of people don’t. They don’t know the subtleties of the difference between a composer and arranger, they think it’s one thing. It’s not. Arranging is a separate craft. Anyway, I’m getting on a soapbox now, certainly, giving a speech.

No, no, no, continue.

The second one was for the GRP All-Star Big Band (ed: for “All Blues” album -1995) and I must admit, obviously, I won that with a bunch of all star musicians, clearly, but I made a deal with Larry Rosen, who was the “R” in GRP, Grusin Rosen Productions became GRP records, just for those who don’t know. So, I was on that label with all those other people like Patti Austin and all the great jazz people of that day, but when the call was going out, I found out that Ernie Watts (ed: Charlie Haden, Frank Zappa, Rolling Stones) had been approached to play the baritone sax. He said: “No, I don’t want to play the baritone sax” and I believe maybe Bob Mintzer (ed: Yellowjackets, Buddy Rich) or Eric Marienthal (ed: Chick Corea), I forget now, said “no” as well. Anyway, no one wanted to play the baritone sax and so Larry said: “Tom, you gotta help me out here. Will you play the baritone sax?” I mean, I played it before but I don’t take solos on it generally or any of that. I said: “I will tell you what, Larry, have you named a leader of this band?” He says “no”, “Make me the leader of the band and I will play the baritone sax”. That’s why that Grammy sits in my living room fireplace mantel (laughs). So, that was a collaboration.

The third one that was a collaboration also with Chaka Khan and the band called The Funk Brothers. It was part of a documentary called “Standing in the Shadows of Motown” (2002), which was the story about all those musical sidemen in Detroit who made all those Motown records and collectively had more hits as a band with various artists like Smokey Robinson and Stevie Wonder and all those people, than The Beach Boys, The Beatles and the Rolling Stones combined, but nobody ever knew their names. So, this documentary was an attempt to show people who these people were and by this time they were all in their 70s and 80s. They brought me along because Junior Walker, who had played on “Shotgun” (1965), he was the saxophone artist in those days, had passed away, so, they needed somebody to sit in, so to speak, playing the Junior Walker stuff. So, I was in the band and I share this Grammy with Chaka Khan and the members of The Funk Brothers on the track “What’s Going On”. I played the soprano part (ed: he sings melodically) : “Paaà da-rla daà da”, all those licks which are part of the famous Marvin Gaye song. I’m very proud also because I just got my 14th Grammy nomination.

Congratulations.

Congratulations.

Thank you. It was part of a band led by a young wonderful lady, Nicole Zuraitis, singer/songwriter, pianist and her band, they came out from New York and we made a live album in Las Vegas (ed: “Live at Vic’s Las Vegas”), I was part of it and the record got nominated for a Grammy, so, that’s great. But I’ve been nominated for a bunch of different things (ed: he looks at the wall behind him where he has the Grammy nominations framed). Let’s see: “Best Fusion Performance”, “Best Instrumental Performance”, “Best Jazz Performance by a Soloist”, they have all these categories that have changed over the years. What’s this one? “Best Jazz Fusion Performance”. When jazz fusion started coming in, they didn’t know how to deal with it because it wasn’t straight ahead, so, over the years the categories kept changing but I kept getting nominated, as I say, until this year, 13 times. I’m actually, in a way, more proud of that because who wins is more like a popularity contest than anything else, but to be one of the five, that is recognized for achievements in performance, I think it’s a great honor.

Ron Carter (Miles Davis Quintet -double bass) told me two years ago that the first take in the studio is always the best, because the first time you play the music, the second time you play yourself. Do you agree with this?

I think that’s coming from a jazz player. It can be true, there is no question. You know, the solo I played on “Listen to What the Man Said”, I hadn’t even heard the tune. In fact, I didn’t even know I was being recorded, to be honest with you. I had my horn out, I thought I ‘d put the headphones on and I’d just play, and here’s the mike and I’d write a thing. I’m just learning the song and I start to play instinctively and it turns out that that’s the take that’s on the record, but there was no thinking involved. It just came straight from the heavens through me and out of the saxophone. It happens. I don’t disagree with Ron, but I don’t agree that’s always true. It’s true sometimes, but sometimes there is a little flaw and you want to go back and correct it. So, you do a second take. Some people like, say, oh, Steely Dan (laughs), no, not them; Michael Masser is a better example, 10, 11, 12, 13 takes, what the hell are you looking for? What could that next take have that one of those others doesn’t have, but they do it, anyway. So, I partially agree with it, let’s put it in that way.

There is a photo of you with Clint Eastwood, Arnold Schwarzenegger and George Lopez at the Museum of Tolerance in 2010. How did it happen?

Yeah, Clint Eastwood was being awarded for his advancing of better racial relations because he had done that movie “Gran Torino” (2008) and he’s got Hmong neighbors and there is a whole racial gang thing going on around this old man and what he does about it. So, he got this award and among the performers were me, I played because he had done the movie “Bird” (1988), I came out and did “Just Friends”, one of the famous Charlie Parker tunes and George Lopez did some comedy, Arnold Schwarzenegger was just there as a celebrity guest, so, the four of us ended up in the picture. Very nice.

George Harrison’s music, Santana’s music, Jimi Hendrix’s music had also a strong spiritual aspect. Is today’s music spiritual?

Very little, that I have ever heard, unless you are talking about the kind of music that they play at church, the Christian pop music, I suppose you can call that spiritual, but I would say “no”. Music unfortunately has become far more consumed by commercial concerns, how do I do something that makes money, rather than coming up with something that’s from your heart. I’m not saying that’s true in all cases but that tracks is the general direction of pop music today. I hope it changes, I hope it goes back to people appreciating people singing, composing and writing from their heart.

Tony Williams (drums) came from Boston and joined Miles Davis when he was 17 years old. Are there those kinds of opportunities nowadays?

I think the music business is much more difficult today to make a good living. There are a number of reasons for that. The most glaring reason would be: You can’t make any money off records anymore because Spotify and iTunes they are in league with each other -if you’ll pardon me the expression- to screw the artists out of their proper royalties. They refuse to recognize the traditional percentages that artists have been paid by the old system, you know, the record sales and the CD sales and all that. Their attitude was: “Well, we are different medium, we don’t have to abide by these rules”. So, I and many of us, have been involved in an attempt to raise the performance rate paid by streaming services to one cent at the time. A couple of years ago, I went back to Washington DC, with a few other people, because they passed a thing called “The Music Modernization Act”, in the Congress of the United States. So, I went to thank a few people, the senators and congressmen, who made that possible, but it’s still just a fraction of what it really ought to be because here’s the thing: You can’t support yourself as a songwriter now or as an artist. You can’t make enough money, because you can get a million streams and make $35, I mean, I’m exaggerating, but you get my point. It’s not money that you can live on and back in those days you could live if you had hits or a string of successes. Listen, I lived off primarily being a session player and a TV and film composer, so, I didn’t have that particular concern personally, but certainly I’m sympathetic to it and I think it’s a horrible turn of events to have these streaming services being so selfish and not sharing the wealth that has been provided to them by these artists.

Was it an interesting experience to meet President Gerald Ford at the White House with the George Harrison band in 1974?

It was great. He actually took us to the Oval Office. It was Ravi Shankar, George’s dad, Harry Harrison -nice old guy, he was great-, George, Billy Preston and me. I don’t remember exactly, maybe there were one or two more people but we were representing the George Harrison tour and that was because Jack Ford, the son of the President Gerald Ford was going to a school in Utah and went to one of the concerts and he said to George: “You are gonna play Washington, right?” George said: “Yeah”. “I’m gonna ask my dad if you maybe come visit The White House”, “Great” and lo and behold it happened. So, what killed me was that they allowed us to go up to the 3rd floor, where actually the residence of the Ford family was and there was a daughter (ed: Susan Elizabeth), she was 17 at the time and I remember walking by her bedroom in which the door was open and I look in there and it’s like a hurricane hit, it was like pillows, sheets, dolls and stuffed animals, all over the place and I thought: “This is a real family living here, boy. This is the real deal” (laughs). I took some comfort in that actually that these are not puppets or plastic people, these are real people and I got such a warm vibe from Gerald Ford. I was never a Republican, I leaned more to the Democratic side, but I consider myself more on the center of them. The only place where things are actually getting done in the politics is when the people in the center come together and agree on something. These extremes on the outside, they don’t help. I understand their passion for whatever they believe but it’s not gonna help get anything done. So, I think he was basically a centrist, too, but I just liked him, he was like your dad. Just sweet man, very loving guy.

Are you optimistic about the future of jazz?

I’m certainly not predictor of anything. I will tell you one story, though: I did a session for a movie that was out last year in America called “The Last Showgirl” (2024) and the composer, Andrew Wyatt is his name, asked me because he writes dramatic music and a lot of pop songs with Miley Cyrus and others, he’s really quite spectacularly successful at that, but he needed to have a big band sound in one of these casinos because there was a period piece of the showgirls in Vegas and he wanted this instrumental sound like Frank Sinatra’s “Sinatra at the Sands” (1966) with Count Basie. So, I took the tune that he wrote and made a big band arrangement of it and at the session, in the booth, there was the director, who was actually Francis Ford Coppola’s granddaughter (ed: Gia Coppola), it’s cool to be her and a few couple of people, but there was this gorgeous girl about 23 and she was very quiet and didn’t say anything and I thought: “I’m talking to everybody, maybe I should introduce myself” and I say: “Hi, I’m Tom. Are you friend of Andrew’s?” and she said: “Yes” and I said: “So, what do you do? What are you doing in life? Are you a music person?” and she said: “I’m a jazz and R’n’B DJ” and I said (ed: surprised) : “You are”. My relationship with that young lady has become wonderful, we are dear friends and I have a radio show in Los Angeles, actually you can stream it on https://kkjz.org/programming/archivedPrograms , you can stream the prior two episodes. I’m on for an hour a week on 21:00 PT on Tuesday nights. We‘ve done something like 220 shows. That was something else that we started with my friend Joe Vella, the producer, during Covid, the podcast and the radio show, both started back then and they are still going strong today. And I started talking about jazz to her and there wasn’t a jazz record from the ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s that I could name that she didn’t know or had in her vinyl collection of over 4.000 recordings. She said: “I go to swap meets, I go when they have sales of old records and stuff and I go through and buy stuff”. She is a collector of jazz. I would like to say she represents the future of jazz. People like her will continue to promote it long after I’m gone. That’s my hope.

All photos courtesy of Tom Scott.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Tom Scott for his time.

Official Tom Scott website: https://www.tomscottmusic.com

Official Tom Scott Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/tomscottjazzman