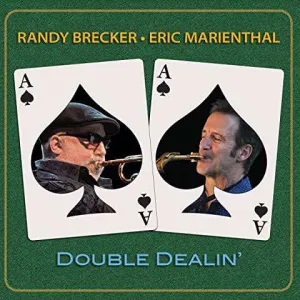

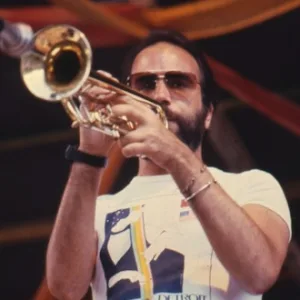

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: April 2024. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary trumpet and flugelhorn player and 7-time Grammy winner: Randy Brecker. He is best known as a member of The Brecker Brothers with his late brother, Michael (saxophone). He was also a founding member of Blood, Sweat & Tears and has played with Horace Silver, Bruce Springsteen, Todd Rundgren, Jaco Pastorius, Frank Zappa, Donald Fagen, Dreams, The Eleventh House and many others. In 2020 he released “Double Dealin’” album in collaboration with Eric Marienthal (saxophone). Read below the very interesting things he told us:

How much did Covid affect the making of “Double Dealin’” (2020) album with Eric Marienthal (saxophone)?

How much did Covid affect the making of “Double Dealin’” (2020) album with Eric Marienthal (saxophone)?

Well, it had a big effect because our original plan was to record together probably in LA, since that was where both of the people involved live. I was going to go out there but when Covid hit that became impossible, so we each recorded our stuff in our respective studios at home.

The chemistry that you and Eric Marienthal have on “Double Dealin’” album is amazing! How natural did it come about?

We play together with various groups, particularly The GRP [All-Star] Big Band and other recordings. We ‘ve known each other for a long time, we always enjoy each other’s playing and we are very close friends. As a matter of fact, we just did the Jazz Cruise together in which he is the music director now and we ‘ve both been on those cruises for several years. So, we are very close friends and we know each other’s playing very well, so it was very easy to do the recording like we did.

I am addicted to “True North” from “Double Dealin’” album. Please tell us everything we should know about this song.

That’s one of my favourite tunes on the record, too, but it was written by George Whitty (ed: keyboards, production, co-writer) and Eric, they collaborated on that one. So, some tunes have a backstory. The way this happened was: George Whitty, we gave him a couple of tunes of ours. This is the idea behind the whole record: To have two or three tunes from each of us and we started when Covid hit. George did sequences and arrangements of all the tunes and slowly we put our parts on after we had the sequences, pretty much at that same time. I think I did the preponderance of the trumpet and flugelhorn work because sometimes there is only one trumpet or flugelhorn on some of the tracks before Eric. But we were all kind of working at the same time because we know each other so well. It just all worked out perfectly, even mixing the record we had no probem, but I do like that tune, too. “True North” is one of the best tunes on the record. I’m not sure what “True North” even refers to; I should have asked at the time. It’s a great tune.

What are the current projects you are involved with?

What are the current projects you are involved with?

The most recent thing, which is just out, is not a project by me, although there is one after that I will talk about, but the main thing that we ‘ve been doing and it came out in the middle of January is a record called “The Hidden World of Piloo” by my wife, Ada Rovatti, who is a wonderful saxophonist and composer. She wrote everything on the record and I helped as co-producer putting the thing together and just giving suggestions as producers do, but she didn’t really need much help, she really knew what she wanted. On this recording there are four vocalists on different tunes. She wrote the lyrics, the string arrangements, the horn section arrangements which is basically her playing alto, tenor and baritone (ed: saxophone) and flute and me playing trumpet or flugelhorn or muted trumpet. The tracks were done in Germany actually, in Bonn, at a great studio there using mostly European musicians. Ada is from Italy and I had recorded in the studio many times, which is called Hansahaus, that’s where a couple of my big band records with WDR were mixed by a great engineer called Klaus Genuit, so I thought that would be a good idea to use my good friends from Europe that were part of the Wolfgang Haffner group.

There is a funny story: When we got there Wolfgang Haffner, who is a very famous German drummer, who I play with a lot, he’s very popular there; I just toured with him and he hurt his hand, so he was unable to play, believe it or not. We didn’t find that until we flew and took a train all the way from Long Island to Bonn, Germany. But we ended up with a very fine young drummer (ed: Tim Dudek) that no one had ever heard of but it just turned out to be great. We said: “Let’s try it, since we are here, anyway” and we recorded the tracks there and then we took all the files on and put our parts on, the singers who were all great. One is Kurt Elling, who is very well-known all over the world now. Also, Niki Harris, who has been Madonna’s background singer. She does the Jazz Cruises every year; she is a wonderful soul singer. Also, Fay Claasen from The Netherlands, who is married to one of the saxophonists in the WDR Big Band. We are fans of her, she is very well-known in Europe, she sang one (ed: “Hey You (Scintilla of Sonder)”). And a young singer named Alma Naidu, sang the fourth one (ed: “Life Must Go On”).

But the main thing is: She wrote all the lyrics and the vocals tunes came out just great. The record now is #10 with a bullet on JazzWeek Radio Charts, so it’s getting a lot of airplay and got a lot of rave reviews. We were really many-many days in the studio to put it all together. It was like putting a puzzle together, so to speak, with so many moving parts, but we had a lot of fun. Since we are married, we can do it together in our basement studio, just think of ideas and record our parts. It’s funny how our records are done now, for the most part, with everyone having their own studio in their basement or somewhere in their house. We ‘ve done hundreds of projects there. It’s become kind of a cottage industry for us, for people all the time send us tracks from all over the world, I mean, literally all over the world and we record and send the files back, filesharing, making records. I rarely do a live record date although I did one with George Garzone (saxophone) recently in New Jersey at Rudy Van Gelder Studio. There were some great players like Jeff “Tain” Watts (drums), Santi Debriano (double bass) and others.

How helpful was the period you played with Horace Silver (piano) to your later career?

How helpful was the period you played with Horace Silver (piano) to your later career?

That is the main part of my older career. I played with Horace in two different bands for substantial amount of time. The first band, all young players, including myself on trumpet and flugelhorn, Bennie Maupin on saxophones and sometimes bass clarinet. I think he played a little bass clarinet in the band before (ed: Miles Davis’) “Bitches Brew” and he was wonderful, one of my idols. He was a little older than me in the frontline and a little more experienced, but he was great to play with. The two guys in the rhythm section was a young Billy Cobham (ed: Miles Davis, Mahavishnu Orchestra – drums), who just got released from the Army, I think this is one of his first gigs and John B. Williams, who was a wonderful young bass player, studying with Ron Carter (Miles Davis Quintet) at the time. So, that was the first band and we were together for almost two years and we toured in Europe and all over the US for most of the time.

It was just an amazing experience playing with these guys and playing with Horace, playing all these great compositions that I had grown up with and seeing the world, so to speak. We travelled all over the United States, we ‘d spend two or three weeks in Southern LA playing for people who lived in that area. We ‘d play at the Half Note in New York City and then at the Village Vanguard, so it was a life-affirming and a life-changing experience for me to play all the wonderful Horace Silver music. I rejoined Horace in 1973, I had some time open and he was starting a new band with my brother, Michael Brecker (tenor saxophone) and the great Will Lee on bass, who is very well-known in the US as a studio player, but he was also a great jazz player on electric bass and a very young Alvin Queen (drums), he was only 17 years and we recorded some of those tunes on a record called “In Pursuit of the 27th Man” (1973) by Horace Silver, which became one of Horace’s most played records and that was another close to a year and we just had a lot of fun. I grew so much having my brother there, Alvin and Will. So, that was another great period with Horace Silver.

Could you share with us the interesting story behind “Sneakin’ Up Behind You” from the first Brecker Bros album (1975)?

Ok. I will tell you the whole story behind the record: I had written nine compositions for all my friends and we were rehearsing for weeks songs like “Skunk Funk” and “Sponge” and I had decided to use my brother on tenor saxophone and a great friend, David Sanborn (alto saxophone), who I went to band camp with, as the horn section and people that were in a band that we previously had called Dreams. Don Grolnick who I also went to camp with on piano, Will Lee again on bass, who was also with Dreams, Chris Parker on drums and a new friend then, Steve Khan (guitar). It was like a rehearsal band. Steve was writing and Grolnick was writing, we got together every week and rehearsed our tunes. But then I got a phone call from a guy named Steve Backer who had just signed a production deal with a very famous record company person named Clive Davis (ed: president of Columbia Records), who had started a new label called Arista. Clive, who had signed us to Columbia with the band Dreams, he knew about us and heard about the music that I had been writing and would sign us sight unseen and I said: “That’s a wonderful deal”, but Steve said there was one caveat.

The caveat was: “I want you to call the band ‘The Brecker Brothers’”. First, I said: “No, no. This is supposed to be a solo record that I ‘m writing. I ‘m writing all the material and I have it very clearly in my head. I have nine tunes that I want to record” but they stuck to their guns. They knew Michael was a diamond in the rough; he had started writing. In other words, they wanted them, they wanted The Brecker Brothers’ name on the cover. Eventually, I gave in. It was too good of a deal to turn down, even though Michael wasn’t really involved. He just played on the record. He hadn’t really thought of a career yet. He was still kind of developing, as with Sanborn, who was the third horn and I told Clive when I had a meeting with him and Steve Backer: “Now, it’s gonna look funny because there are three horns in the frontline, so we tend David Sanborn as our long lost cousin or something, if you are gonna call it ‘The Brecker Brothers’”. Anyway, we had a second meeting and this was concerning “Sneakin’ Up Behind You”. Clive called me up to his office. We had recorded all the nine tunes and went really well. Steve Backer complimented us so many times.

He said: “You know, I’ve never worked with musicians this professionally. When you come in, you know exactly what you are gonna do and you did it. Usually, with jazz musicians who I work with in the studio, they come in kind of unprepared and they say: ‘Ok, what you wanna play?’ It’s looser”, but we knew exactly what we needed to do. We recorded the nine tunes and Clive called a meeting with me and he complimented me on the nice tunes. He said: “These sound great but, young man, you need a single” and I said: “Well, we just have these nine tunes” and he was very diplomatic but he said: “Look, you need a single and I love the music you recorded, but without a single we can’t do anything with it. You need a single to outsell the record”. So, I trudged back to our rehearsal studio and I explained the situation to all the guys and we had a method: We were very good at jamming up tunes from nothing. Grolnick had an idea, he had a horn line. He said: “You guys play this horn line”, he played it on the piano: “Ti-ti ti-ti ti-ti ti-ti-tat, ti-ti ti-ti-tit” I can’t sing it, but that was the first idea. Everyone started coming up with ideas and we jammed up “Sneakin’ Up Behind You” in about four hours. We recorded it on cassette, we all had cassette players and then we listened and we refined it a little more. Will Lee thought of the title and he sings: “Sneeeak-in’ Up Behind You”, he thought of the lyrics and he wrote the little section in the middle that was kind of disco-oriented.

He said: “You know, I’ve never worked with musicians this professionally. When you come in, you know exactly what you are gonna do and you did it. Usually, with jazz musicians who I work with in the studio, they come in kind of unprepared and they say: ‘Ok, what you wanna play?’ It’s looser”, but we knew exactly what we needed to do. We recorded the nine tunes and Clive called a meeting with me and he complimented me on the nice tunes. He said: “These sound great but, young man, you need a single” and I said: “Well, we just have these nine tunes” and he was very diplomatic but he said: “Look, you need a single and I love the music you recorded, but without a single we can’t do anything with it. You need a single to outsell the record”. So, I trudged back to our rehearsal studio and I explained the situation to all the guys and we had a method: We were very good at jamming up tunes from nothing. Grolnick had an idea, he had a horn line. He said: “You guys play this horn line”, he played it on the piano: “Ti-ti ti-ti ti-ti ti-ti-tat, ti-ti ti-ti-tit” I can’t sing it, but that was the first idea. Everyone started coming up with ideas and we jammed up “Sneakin’ Up Behind You” in about four hours. We recorded it on cassette, we all had cassette players and then we listened and we refined it a little more. Will Lee thought of the title and he sings: “Sneeeak-in’ Up Behind You”, he thought of the lyrics and he wrote the little section in the middle that was kind of disco-oriented.

We went in the studio the next day and Clive came to the session and thankfully we were looking up to God because if he didn’t like it, we would have been sacked. But he loved the tune, he was so excited when he heard it. He just ran out of the studio and he said: “That’s it, you ‘ve got a single!” and lo and behold he really liked it and he pushed it and it became a hit. On the R&B charts it rose to #2 on Billboard. That’s what really sold the whole record and the next thing we know we are out on the road and we were opening shows for people like Chaka Khan, Parliament-Funkadelic and the record got up to the 50s in the Top200 in Billboard, as a result of “Sneakin’ Up Behind You” being a hit. So, it was happenstance and Clive was a genius, he knew how to sell records, that’s for sure. The record ended up selling close to -gee- 400.000-500.000 records and we were very excited at the success. You know, we ‘d buy Billboard every week to see where it was in the charts. I had never thought of going that far with this project. It was like a hobby for me because we were all so busy doing other people’s records in recording studios. So, it was a very interesting story how happenstance intervened in our lives and Clive was great in making us world-famous.

How much did Miles Davis’ “Bitches Brew” era influence the music of the Brecker Brothers?

Not very much, actually, although I liked it, but I didn’t want to go in that direction because Miles had a more open thing in mind. I thought he was a genius in his own right. I just think I was there when Bennie Maupin, for instance, with Horace Silver, picked up the bass clarinet at a store and start practicing bass clarinet in his room. I mean, Miles Davis was wise enough to hear that and use Bennie’s sound on “Bitches Brew” throughout the record, not playing with the other people but it becomes a texture, the bass clarinet or sometimes having two bass players, an upright player and an electric player playing at the same time. But it was very open playing: When they went into the studio they were not even sure what they were gonna play, which it was the opposite of the way we went into the studio. I had arrangements worked out for everyone, practically every note written out. Of course, there were improvisational solos, but we had charts while “Bitches Brew” had no charts. It’s funny that you ask this, I just saw a film on Harvey Brooks, who was playing one of the basses on “Bitches Brew” and he explained how Miles worked: He just went in the studio and Miles said: “Play”. They ‘d set up and they would play, he would record it, then they would take the tapes and edit the tapes and turn them into music.

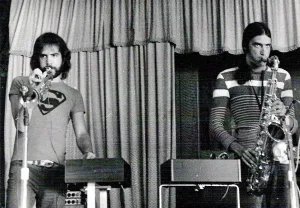

That record didn’t have much of an influence at all on Brecker Brothers. If anything and I’ve told the story: We had a band called Dreams before Brecker Brothers with a lot of the same people. Myself, a wonderful trombone player named Barry Rogers, Will Lee on bass, Don Grolnick (piano), the great Billy Cobham on drums. It grew out of Horace Silver’s band and others. We were a house band in New York, at The Village Gate and by then I was playing a wah-wah pedal, because in Dreams, John Abercrombie was the guitarist and he used the wah-wah pedal οn all of the solos and there was one time when he couldn’t make the rehearsal. We all had electric hook ups on our instruments, to be able to hear ourselves. We hopped up to a thing called Condor made by the Hammond company, that had different sounds if you ‘d get out of the box like watery sounds, nothing too great, but there wasn’t much available. At this one rehearsal, Abercrombie left his wah-wah, he couldn’t make the rehearsal, so I plugged his wah-wah into my chain of quarter inch jacks, and boy, on trumpet it sounded just great. We flipped out, that you could use guitar stomp boxes on horns and they would be great, so, we got more stomp boxes. My brother particularly sounded good on a Funk Machine as did Barry and Miles would come and hear Dreams.

That record didn’t have much of an influence at all on Brecker Brothers. If anything and I’ve told the story: We had a band called Dreams before Brecker Brothers with a lot of the same people. Myself, a wonderful trombone player named Barry Rogers, Will Lee on bass, Don Grolnick (piano), the great Billy Cobham on drums. It grew out of Horace Silver’s band and others. We were a house band in New York, at The Village Gate and by then I was playing a wah-wah pedal, because in Dreams, John Abercrombie was the guitarist and he used the wah-wah pedal οn all of the solos and there was one time when he couldn’t make the rehearsal. We all had electric hook ups on our instruments, to be able to hear ourselves. We hopped up to a thing called Condor made by the Hammond company, that had different sounds if you ‘d get out of the box like watery sounds, nothing too great, but there wasn’t much available. At this one rehearsal, Abercrombie left his wah-wah, he couldn’t make the rehearsal, so I plugged his wah-wah into my chain of quarter inch jacks, and boy, on trumpet it sounded just great. We flipped out, that you could use guitar stomp boxes on horns and they would be great, so, we got more stomp boxes. My brother particularly sounded good on a Funk Machine as did Barry and Miles would come and hear Dreams.

He was always there in the back, you always knew when he showed up because everybody was saying: “Hey, Miles is here”, “Miles is here”. He never said anything to us, he would just sit in the back and listen to what we were doing. That was a great band (ed: Dreams) that did two records on Columbia, we were signed -again- by Clive Davis. It never had a commercial success because we had no singles, that’s what you needed then. But it was a big influence on other musicians in New York including Miles Davis, that’s how it worked. It was funny, years later, I never really met him, I ‘m sorry this is a long story, but we had opened a club called Seventh Avenue South and one night it was crowded and I was standing next to Miles and I held on my hand and I said something really stupid: “Hey, my name is Randy Brecker, a trumpet player and I’m a big fan of yours, Miles” and he turned around and looked at me and he had his shades on, bug eye large shades and he just looked right through me and he didn’t say anything. I said: “Ok. Well, nice to meet you” and he didn’t say one word back to me. So, I dejectedly went out to the bar and I was sitting at the end of the bar for a couple of hours drinking some vodka to drown my sorrow that he didn’t answer me and I heard a little puff there and I heard: “I love my wah-wah. Do you love your wah-wah?” and he just split. It was Miles, he whispered that into my ear and then he left. So, I think he was acknowledging the fact that he heard me playing wah-wah and he started doing it. That’s an interesting side story to the whole scene at that time.

I am huge Todd Rundgren fan and I ‘ve talked with him, too. Do you remember recording “Dust in the Wind” and “Hello It’s me” from his “Something/Anything?” (1972) album?

Oh, Todd Rundgren, yes, sure. There are certain sessions that I remember, because on that session everybody was in the studio at the same time, that’s how he wanted to record. There were no isolation booths, no anything. The singers were there, the instrumentalists were there, in the center of the studio and we cut “Hello It’s Me”. We jammed up, me, Michael and the gentleman I talked about before, Barry Rogers, a great trombonist. We jammed up some horn parts on the session, because we rehearsed a little beforehand and that record became a million seller. We only did one or two takes. He would go: “One, two. One, two, three, four”, we did a couple of takes and next thing we know the record was on the charts and it sold millions. Interestingly enough, Todd Rundgren, Mike and I had met earlier in Philadelphia where my father who was a musician had bought a B3 organ made by Hammond and he didn’t play it much, so he ended up selling it to local Philly rock band called The Nazz and it turned out that that was Todd’s band in Philly. We were talking one day and we realized that he bought my father’s organ in Philadelphia before he moved to New York and became famous. We ended up doing the first Brecker Brothers record in a studio called Secret Sound, that was actually owned by Todd. That’s how we got to know him.

“Meeting Across the River” (from “Born to Run” -1975) is my favourite Bruce Springsteen song and you played on this. Do you remember that session?

“Meeting Across the River” (from “Born to Run” -1975) is my favourite Bruce Springsteen song and you played on this. Do you remember that session?

Yeah, I remember that one, too. That tune, honestly, was an overdub. He had it all already tracked, so I just played the horn with what they had and he enjoyed what I played, so he left it on there and they still play that tune. I ‘ve seen different versions where they utilize (ed: his parts) -sometimes they don’t, sometimes they do- but somebody transcribed my trumpet playing on that record and quite often whoever is playing trumpet plays my solo as part of Bruce’s live show. I had previously met him right before we went into the studio and hung out a couple of nights. The session now was very interesting with another tune, “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out”, where there was no music. The horn section was me, Sanborn, my brother and a very fine trombone player named Wayne Andre. So, we had to jam up the parts and this was real rock ‘n’ roll, so it was a little out of my comfort zone. We had trouble thinking of what to play, it was really a rock tune and got about halfway through the song and we weren’t really happy with what we were doing, but all of a sudden there was a lot of motion and energy in the control booth and we hear a voice saying: “Wait a minute! Wait a minute! That’s not it! That sounds terrible! That’s not what the song needs” and it turns out that that was Bruce’s well-known guitar player, Miami Steve Van Zandt, who became a star in his own right, but he really helped us then. He helped write the chart, we started all over and he found us some good lines that would fit. He was really a rock ‘n’ roll guy. So, we threw out most of the stuff we had done, we used his ideas and we arranged the voicings; it took quite a long time to do that one, but I remember the whole session. Then, Bruce had another tune and I put a solo on “Meeting Across the River”. By then, I was pretty fried, but it’s a good solo, it has a lot of soul; I think I had been in the studio for many hours. We stayed in contact for a while, I haven’t seen Bruce in many years, but he married a lady who both Mike and I knew, Patti Scialfa, who had moved to New York and was a receptionist at a studio, Mediasound, that we both worked at a lot. She was working on tunes and writing lyrics as a receptionist. She eventually married Bruce and he did some of her material and she became very well-known and they are still married, all these years later.

What do you think today about Blood, Sweat & Tears’ “Child is Father to the Man” (1968) album?

At the time, I was enjoying it and now, more than 50 years later I think that’s one of the classic rock records of the ‘60s, one of my favourites. It’s all centered around the great Al Kooper (ed: Bob Dylan, “Super Session” -Hammond, vocals) who had the idea to add horns to the band and utilizing the arranging of horns of Fred Lipsius (alto saxophone), who I talk to all the time. Fred has a new record out (ed: “Joy!” -2024). He is 80 now, I’m 78 and I play on his new record all these years later. But I think that record “Child is Father to the Man” is a classic. Every tune sounds great to me. It’s not my particular way of playing since I was more of a jazz artist, but I think out of the rock ‘n’ roll of the ‘60s, it was really a rock ‘n’ roll record with a little soul thrown in. Great tunes, great arrangements and I loved the way Al sang. I was sorry to see him go, and I left Blood, Sweat & Tears, because I wasn’t playing enough. I was only playing one solo a night and Horace Silver called. We had a band meeting and the other band members told Al that they thought the band needed a lead singer and they had found somebody in Canada named David Clayton-Thomas.

They wanted to bring him into the band and be the lead singer and Al didn’t buy it and he said: “No, I want to be the lead singer. If that’s what you wanna do, I quit” and he walked out of the meeting. I chose this time to say: “You know, guys, I hate to say it and I love playing with the band, but I don’t get to play enough and Horace Silver called me to join his quintet, where I can really be a jazz musician and play on every tune and as a great band with Billy Cobham on drums” -who no one ever heard of yet- “but it ‘s a very nice opportunity. I ‘ll find you a good trumpet player to take my place, but I am gonna also leave the band tonight” and they begged me to stay. They said they were gonna cut me equally, all the horn players were gonna be on equal par with the rhythm section, but I said: “No, this is something that I really have to do. I wish you guys good luck” and then next day I was in the Joe Henderson big band rehearsal and my friend, Lew Soloff, who was sitting next to me, a great trumpet player and he didn’t want to do the gig. I said: “Listen, I ‘ve been on the spot, Lew, I have to find a replacement in Blood, Sweat & Tears ‘cause I’m joining Horace Silver and you ‘ll get paid a salary whether you work or not”.

They wanted to bring him into the band and be the lead singer and Al didn’t buy it and he said: “No, I want to be the lead singer. If that’s what you wanna do, I quit” and he walked out of the meeting. I chose this time to say: “You know, guys, I hate to say it and I love playing with the band, but I don’t get to play enough and Horace Silver called me to join his quintet, where I can really be a jazz musician and play on every tune and as a great band with Billy Cobham on drums” -who no one ever heard of yet- “but it ‘s a very nice opportunity. I ‘ll find you a good trumpet player to take my place, but I am gonna also leave the band tonight” and they begged me to stay. They said they were gonna cut me equally, all the horn players were gonna be on equal par with the rhythm section, but I said: “No, this is something that I really have to do. I wish you guys good luck” and then next day I was in the Joe Henderson big band rehearsal and my friend, Lew Soloff, who was sitting next to me, a great trumpet player and he didn’t want to do the gig. I said: “Listen, I ‘ve been on the spot, Lew, I have to find a replacement in Blood, Sweat & Tears ‘cause I’m joining Horace Silver and you ‘ll get paid a salary whether you work or not”.

I think it was like 100 a week, so, that’s two $50 gigs you don’t have to do. You get paid even if you don’t work, you are on salary. So, by the end I talked him into taking my place and then the rest is history. They went in and did the second record (ed: “Blood, Sweat & Tears” -1968) and it sold 11 million copies, so it was #1 record for a year. It won a Grammy, The Best Album of the Year, their salaries went up 5000%, they all bought houses in Mid Valley. I was making 250 with Horace Silver, by then they were making 5000 a week and Horace took our taxes out, plus we had to pay for our hotel. So, Lew and I would go to a trumpet lesson every week and he started picking me up in a limo to drive up to New Jersey to study with a guy named Edward Treutel and left the whole way. But in the end, it really worked out well for me because I really enjoyed playing with Horace and I went to write my own music through watching Horace, I wrote lyrics because Horace wrote lyrics to all those tunes. He really set me on a path that I wouldn’t have ordinarily gone had I not joined his band. He was such an influence on my writing, playing and just my life.

You recorded on Donald Fagen’s (Steely Dan -vocals, keyboards) “The Nightfly” (1982) album. Is he an easy-going person to work with?

He is easy-going, but at the same time all the Steely Dan triumvirate, which was Gary Katz, who was their producer and Walter (ed: Becker), the guitarist, even if Walter wasn’t there, they were very exact in what they wanted and their way to do records was to do many-many takes, sometimes 30 takes. If you had a four bar solo you would play the solo maybe 20 to 30 times and you knew you were gonna do that, so you ‘d save your best lines for later, because you knew you were gonna do it over and over. But they came up with great records and that’s just the way they worked. They were amazing composers and lyricists and still some of my favourite records to listen to are theirs. They had a big influence on the way they mixed jazz with rock ‘n’ roll and other genres, so it was always a pleasure to work for them, even though was a lot of hard work.

How did it happen to tour with Jaco Pastorius’ Word of Mouth big band?

How did it happen to tour with Jaco Pastorius’ Word of Mouth big band?

Jaco had a band, we played on his first record (ed: “Jaco Pastorius” -1976). Jaco’s name circulated around New York, he was so good even before he got there. Everyone heard about this amazing bass player in Florida who played stuff nobody ever played on the electric bass, so, we were all curious about how he sounded. He lived in the Fort Lauderdale area, in Florida and eventually lo and behold my brother and I, found ourselves at Bobby Colomby’s studio (ed: he also produced Jaco’s album). Bobby was the drummer in Blood, Sweat & Tears, a few years later we were still close friends in New York, a little north of the city and there was Jaco doing his first record and we played on a tune called “Come On, Come Over” featuring Sam & Dave. Jaco did all this amazing playing on bass, “Donna Lee” and Herbie Hancock (keyboards) was there, so, it was a great experience. Then, Jaco formed a band called Word of Mouth with two saxophones, my brother and Bob Mintzer on tenor saxophones. He liked that sound and Mintzer was a wonderful arranger and composer, so he used some of Bob’s arrangements with a big band and it’s on the record. But eventually my brother had substance abuse problems and decided to go onto rehab. This is back in 1982 and he thought that being around Jaco maybe wasn’t a great influence, so he left the band and Jaco asked me to take his place. That’s truthfully how that happened and I stayed with Jaco for a couple of years. We did a long US tour on a bus, coast to coast and eventually went to Japan with a big band and we played in New York and LA with a big band, we played in Chicago with a big band from Chicago, so it was fascinating. Later, Jaco was taken ill with mental illness that was never really diagnosed and also substance abuse, he drugged too much and his career started to go down. He was doing a lot of stuff he shouldn’t. So, the story had a sad ending when he was killed beaten up by a bouncer in a club in Florida and that was the end of the Jaco era, but he was certainly a tragic figure. One of the greatest musicians we have ever produced in America.

How much artistic freedom do you have on other people’s albums?

It depends. Usually, not much. Usually, I just play solos and sometimes they want it to be funky. Horace Silver is a good example. We did a live record in 1997 called “A Prescription for the Blues”. The band was Ron Carter (upright bass), Louis Hayes (drums), Horace Silver, me and my brother, Mike. Horace cautioned us, he said: “Look, on the funky tunes” -which were pretty much all those kinds of blues-oriented tunes on this record, “A Prescription for the Blues”- he said: “I don’t want to hear any 16th notes, play your funky stuff and I want to see the girls shaking their butts in their skirts”, he would give a speech to us all. We would do one of the tunes and Mike was well away but was playing some 16th notes and Horace waved his arms and stopped the take and started to say: “Mike, I told you, I don’t want any 16th notes, I don’t want any ‘bloo-bloo-bloo-bloo’. I don’t want any of that stuff. I want a good funky solo”. So, for Horace Silver that was what you had to do. There were tunes in his repertoire where you could play whatever you want, but more often than not that’s how it is on other people’s records, where they hire you to do a solo and they ‘ll try to tell the style and not to play too many outside notes. Occasionally, I would get asked to write arrangements -back in the day- for people, that was fun. I wrote arrangements for George Benson, Diana Ross, Chaka Khan and others. That part was fun but that’s the way it is. Most sessions, if I wasn’t writing the stuff, they had an arranger and they passed on music or they would send us charts now, we read the music, we put on a solo and try to keep it a little more commercially-oriented. You don’t play a lot; you try to play something that fits with what’s on the record, that’s what we try to do as session musicians.

Are you optimistic about the future of jazz?

Are you optimistic about the future of jazz?

Yeah, I’m optimistic. It’s not for everyone but jazz will always be here because jazz music influences pop music and music all over the world; it’s become global now. Most good musicians listen to jazz and they are aware of it and it seeps into a lot of other styles of music, much more than people think and always has. All the musicians at Motown were jazz musicians, all the musicians in Philadelphia on all those great Gamble and Huff records in the famous soul music that grew out of Philadelphia, they were all jazz musicians, too. All the arrangers were jazz musicians, like Quincy Jones (ed: Michael Jackson, George Benson producer) who was a jazz musician at heart. Same with The Wrecking Crew in LA, all jazz musicians that played on Beach Boys records and Brian Wilson was a great jazz fan. So, I think jazz in itself will always be here, but it’s not for everyone. You have to learn somewhat about the mechanics of how music works, you have to learn something about form and the way improvisation is based on forms of tunes and on chords or modes and you have to relate that to your improvisation. The rhythmical aspect has to be thought about, it’s not like other kinds of music, it has to swing in a certain way. But I’m very optimistic, there are so many young great players playing modern jazz, even way more modern that I did when I was young. You can go to the farthest reaches of the world and you will find great jazz musicians.

I had the honour to do an interview with Larry Coryell. Are you proud of the period you played with Eleventh House?

Oh yeah, that was thrilling, too. I had such a great time with Larry, who I met in 1962, I think, before I even moved to New York. I was chasing after my girlfriend at the time in Seattle, Washington and Larry had a gig at a club called The Embers every night and I would come and sit in. So, we both ended up about a year or two later, he had a group called The Free Spirits, which was literally the first jazz rock band and I was kind of like the sixth member of the band, I would sit in all the time. So, when he decided to form a new band called The Eleventh House, by then I had my wah-wah and all my pedals along with Alphonse Mouzon (drums), they had Danny Trifan on bass and my friend, Mike Mandel on keyboards. That became a very influential band, I stayed with Larry for close to a year and did a couple of records. “Introducing Eleventh House” (1974) I think it stands out as a very good representative of that time period, it’s one of my favourite records. In our 70s we had all stayed friends. You probably know this: We went down to Florida and we did an album (ed: 2017’s “Seven Secrets” by Larry Coryell’s Eleventh House), just like the old days, Alphonse Mouzon, myself, Julian Coryell was on it on guitar, Julian is Larry’s son. Mike Mandel didn’t play on that one, but John Lee played bass, he was in Eleventh House after I had split. The record came out very-very good and we had big plans to tour and record, even though we were all in our 70s, we still sounded good. But suddenly, both Larry and Alphonse passed away within six months of each other, so that was the end of the group. But it’s still a good record and I miss them both very much.

Brecker Brothers played on Frank Zappa’s “Zappa in New York” (1978 -recorded in 1976 record at the Palladium). How did it come about?

Brecker Brothers played on Frank Zappa’s “Zappa in New York” (1978 -recorded in 1976 record at the Palladium). How did it come about?

That came about because Frank Zappa was in New York and needed a horn section and he decided to use the section from the TV show “Saturday Night Live”, but the trumpet player who was my friend Alan “Mr. Fabulous” Rubin, for some reason didn’t want to do the gig or he was busy. I played on “Saturday Night Live” quite a bit myself as a second trumpet, so they called me. Also, my brother was in the band, Lou Marini (alto saxophone), Tom Malone (trombone), Ronnie Cuber (baritone saxophone, clarinet) and me and that’s how it came about. I was stuck in there, trying to learn all the Zappa music. We played at the Palladium theatre on 14th Street for a week and recorded that record and it became very popular. I get asked about more than any other record. They recently released all the four nights, I haven’t heard it but there is some great playing from everybody on that record.

What do your 7 Grammy Awards mean to you?

It’s always nice to win a Grammy, because your peers, the other musicians, vote. So, I’m proud of the fact that I have 7 Grammys and I think I was nominated 20 times. My brother had 15, imagine that, he passed away at age 56. It’s always nice to get recognized by other musicians and people in the business, so it really means a lot. I have them set up in my recording studio just to give me inspiration, to keep going.

Ron Carter (Miles Davis Quintet) told me: “The first take in the studio is always the best, because the first time you play the music, the second time you play yourself”. Do you agree with this?

Yeah, I agree to try to get everything on tape, as soon as possible. First takes are always great but there is a certain aspect: If you get the first take, people are looking at it, that’s an interesting way to do and that’s the way Miles did. He would record without even knowing the tune. The first crack; he would put the music on the bandstand and record and that’s great. I mean, it’s interesting to hear that music, but I like things that are a little more organized, so I am on Ron Carter’s side. The second take, if you know the music, you can put more of yourself, you can fit through a little better, you know what I mean. I think that’s what he meant, so you can organize your thoughts a little better. The first take is interesting but you don’t know what is gonna come next. Miles also said: “You can’t rehearse the future”. He wanted to get everyone’s first impression on the tune and there is something to be said for that, too.

Last month I did an interview with your friend Bill Evans (Miles Davis -saxophone) and he told me that there is no individuality and personal character in smooth jazz; All the players sound the same. Do you agree with this?

Last month I did an interview with your friend Bill Evans (Miles Davis -saxophone) and he told me that there is no individuality and personal character in smooth jazz; All the players sound the same. Do you agree with this?

There are a lot of things as a style that don’t allow for much of anything else. I agree with, but within the smooth jazz movement there are one or two or three really good players that come to mind: Gerald Albright (saxophone) is very good and there are others. Rick Braun of course on trumpet, who is probably the premier, I would call much of his music as smooth, but he is in that class. Most people in that element are also very good showmen or showgirls. You know, they look good, they know how to really entertain an audience and I find there is nothing wrong with that. It’s not something I ‘m very good at doing and I don’t wanna play too smooth music, there is not enough tension in the music and quite a bit everybody sounds the same. But some of it it’s very good. Occasionally, I’m a guest fusion guy on smooth jazz festivals and all the people are very nice. I like all the musicians.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Randy Brecker for his time.

Official Randy Brecker website: https://www.randybrecker.com/

Official Randy Brecker Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/RandyBrecker/