HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: December 2025. We had the great honour to talk with a very talented musician: Patrick Campbell-Lyons. He is most-well known as the founding member, guitarist and vocalist of Nirvana, one of the most original bands of the ‘60s. Their debut album, “The Story of Simon Simopath” (1967) was the first concert album that was ever released and it was one of the earliest examples of the British psychedelic music. Madfish Records just released a 12-CD box set called “Nirvana – The Show Must Go On”. Patrick Campbell-Lyons has also an acclaimed solo career and in 2009 he released his autobiography, “Psychedelic Days”. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

I’m ecstatically happy about it. When I say “ecstatically” I mean, to see everything together after 50 years of work in one extremely well-presented package -the box set itself- put together by Madfish/Snapper, it makes me feel that what I’ve done has been very worthwhile.

Do you think Nirvana – The Show Must Go On” box set is also a good opportunity for younger people to learn about the music of Nirvana?

Oh, for sure. Every release that people have put out in the last years, like the vinyl box set which was called “Songlife”, four years ago. Island/Universal had put out various compilations and each time, new people come on board the Nirvana ship, on the Nirvana train. Sometimes, of course, people find us by accident because of the other group Nirvana. Our presence is very much online because of these releases and continued exposure. One of the big things happened five years ago, “Rainbow Chaser” (ed: from “All of Us” -1968) one of our best songs, was used on a very famous and award-winning American TV series called Ted Lasso. It received many Emmys. On the first episode of the first season they used “Rainbow Chaser” and on the fifth episode of the third season they used a song of ours called “Oh, What a Performance” (ed: single b-side and bonus track on “All of Us”). Of course that has brought many-many people because our presence on Spotify went up like 1.000%.

What are the projects you are currently involved with?

Now, I’m not involved in any projects other than promoting the box set. I haven’t been writing any songs for a year because I was sick. It didn’t mean that I wasn’t being creative; I do other things. I write, I’ve written a lot of poetry. I just didn’t pick up a guitar or go to a piano for year, but I’m thinking about it. I have 6-7 songs that nobody has heard that I’ve been working on, up two years ago and some companies have shown interest in them. So, there is every likelihood now that I feel so much better, that I will go back to them and hopefully complete them in new year. But you know, when you have a project like “The Show Must Go On”, you can do a lot of promotion work for it and that keeps someone busy and keeps one’s mind mentally active. “The Show Must Go On” is a metaphor for life, as you probably know: The show goes on. We gave this title to a song of ours on our second album, “All of Us” and this was even before Queen had a song called “The Show Must Go On” (ed: from “Innuendo” -1991). The idea now that Madfish would call this box set “The Show Must Go On” seems to be a perfect circle. Now the show is going on, the show has gone on, and the show will go on for Alex Spyropoulos (keyboards, vocals), my collaborator and friend and for myself as a solo person. For songwriters, musicians and creative people, I think the show goes on till your last breath.

To put it in a couple of sentences is not easy because it was something that happened as we had our first songs and we just signed with Island Records. We had 5 or 6 songs which they liked and they signed us to a 3-album deal on the strength of those songs and in the process of the writing and making our original demos -which we did ourselves- we felt that something was happening, that the songs had a thread, they had a connection. It’s like the writers, book writers, songwriters, sculptors, painters, they all make something out of nothing. Nothing is there and then something is there. We talked about that quite a few times, when I first met Alex, as a friend; I remember a conversation we had that songwriting was a bit like going against the Law of Physics, shall we say, because that’s what it is: You make something out of nothing. You have a guitar, you have a piano and then… magic, you create something out of thin air. In the process of that entire situation, we were very much in a spiritual state of mind about these things, as much as we were in the ‘60s and we were deeply involved in the culture of it on many levels.

This Simon appeared but his name wasn’t “Simopath”, his name was Simon Psychopath and eventually with a couple of more songs we found ourselves building a small visual scenario, because both had interest in film. We talked about it every day because we used to work every day. The first time we spoke about it, we were talking about it as “a pantomime for grown-ups”. “Pantomime”, as you probably know, is a word of Italian origin, is a show for young people and old people, they can all go to a pantomime, but we were calling our project “a pantomime of grown-ups”. Eventually, his name did become Simon Simopath and we’ve carried it through on a number of occasions in other work that we did, but we never actually had some people pick up on that. Once he became a character, he then took off and he had “Wings of Love”, he was flying and he wasn’t Simon Psychopath anymore. Or maybe a part of him still was, I don’t know. You don’t have to ask many questions about these things.

I’m addicted to “Pentecost Hotel” (from “The Story of Simon Simopath”). What inspired you to write this?

A dream, that involved before the dream maybe quite a bit of indulgence in marijuana pleasure. It’s not like some people said that it was an acid song; it had nothing to do with acid, but in those days I smoke quite a bit of weed and took amphetamines and stuff, like many others. I did have this dream, an out-of-body experience, where I was lying on my bed but I was looking at myself from above, but then for some reason or other, it was all happening in water. The dream became lucid and there was water in, I felt that I was in the ocean, but I was still aware that I was looking at myself and on the bottom of the ocean, on the seabed, there was a wooden boat about 10 metres long, not big, and of course, it had been out there for a while and there was fish swimming inside, it was sandy, the broken mast was still on it and the name on the side of the boat was “Pentecost Hotel”. Are you still addicted?

Yeah, I mean, this is one of my favourite songs of compositions that I worked on with Alex Spyropoulos. In recent years, I’ve written a book about this times (ed: “Psychedelic Days”) and I was touring in America promoting the book and I put together a small band. In fact, it was a band that was backing Dave Davies (guitar) of The Kinks, when he was out there doing some shows. When I had a book reading, I would do about 10 Nirvana songs live and I always did “Life Ain’t Easy” because it was a special song for me. It was always one of the most well-liked and appreciated tunes. It didn’t make it on the original albums because we used to put songs aside. I think we brought it to the record company for “All of Us” and it didn’t make it, it was one of the ones that were put aside for another day. Like many songwriters, you write 10 songs to get one good song. Then you get a couple of average ones that seem good at the end of the whole work. For “Life Ain’t Easy” we had a very good demo that we liked, but there were a few mistakes on the demo, when we made it, we used to use two Revox’s (ed: tape recorders). There were a few mistakes on the demo recording, we used to call it “glitches” in those days, where we went out of tune or something happened on the voice and it began to wobble a little bit and we were a bit embarrassed about playing this sometimes. But we did play it to the record company and they liked it, but they didn’t like it as much as they liked the others. We didn’t push it too much because we thought: “We just didn’t get the best of ourselves on that one”. I agree with you, when I hear it now, it has become one of my favourites, but don’t forget that it has been remixed a few times and digitally worked on.

When you recorded “The Story of Simon Simopath” had you realized that it was the first concept album ever recorded?

No. One-word answer: No. I didn’t even know what the word “concept” meant. I didn’t know. We were living a bit in our own world, we weren’t in that whole pop scene. We had our own social life and working life. So, I wasn’t familiar with things like concept albums, but I think most of these things came after us. “Simon Simopath” (ed: it was released in October 1967) was before The Small Faces concept album (ed: “Odgens’ Nut Gone Flake” -1968) or The Moody Blues concept album (ed: “Days of Future Passed” -November 1967). But none of them -even though they came out later- had this very strong visual concept that could almost be a staged musical or an animated film. In fact, Chris Blackwell, the boss of Island, gave a Polish director some money and the guy came to him with a draft of the lyrics of the album and everything and proposed that maybe he would do an animated version of it, which it should ‘ve been fantastic but he didn’t manage to crack it.

How important was the role of Chris Blackwell (owner of Island Records) to the recording career of Nirvana?

He was everything. Everything. I wrote a chapter in the book about Chris in detail. Of course, it’s 25-30 pages and to put it all in here in a couple of words for you, it’s not easy. Chris was a special man: There are a lot of people who give you contracts, but there is nothing behind this. They give contracts to 10 people and then they’ll throw them like shit against the wall, hoping that one will stick on the wall. Island Records wasn’t that kind of label. Every member on Island Records who signed there felt like a family, because of Chris Blackwell, because that’s the way he made it and that’s the way it’s still today the most relevant and most inventive independent label that ever existed. He was first with everything. He was first with the designs of that era. He started as a man who came from Jamaica, he was independently wealthy, he had lost a lot of money on other projects in America or West Indies. I think one of his parents was Jamaican and one was British. His father had something to do with importation of sugar and things like that, way back. He came to prove himself and of course he started with reggae music and calypso. When he saw what was happening in London he thought: “Well, I’m going to try this” and he was an innovator.

Most record companies say: “Your royalties are going to be this” and you will be waiting for your money, if you ever get it, because they take bits off for this and that and “you bought a shirt and we paid for it”. Island Records had Traffic, Spooky Tooth, The Smoke, Nick Drake, John Martyn and of course we had Free, they were very important. Also, there was a band called Wynder K. Frog (ed: Mick Weaver -Hammond) and they had two writers: Jackie Edwards who wrote “Keep on Running” (ed: #1 hit for Spencer Davis Group) and Jimmy Cliff. He brought them from Jamaica, they worked a little bit, they were there, but they hadn’t releases on the pink label (ed: until 1970-71). I mentioned about royalties when you signed an agreement. Chris Blackwell did a very clever thing: He paid everybody a salary, a very liveable salary. All the artists used to turn up at Oxford Street every Friday and we would pick up our wages. Alex and I were, I think, on £60/week each. It was a lot of money for those days (laughs). My rental was only £7. Of course, you ‘d meet everybody there.

Of course, later on, when we started making money, he got the money back, but he never made any money from the original Island records. Chris Blackwell didn’t make any money until he remixed Bob Marley and the Wailers’ “Exodus” (1977) album. That’s when he went from the red into the black, because he had put so much money into things like Cat Stevens, Roxy Music… The label changed after we left, the logo changed, it wasn’t pink anymore, it was white with a palm tree on it and he kept doing it. I think he stopped the wages situation once the pink label finished (ed: in 1970-’71). He was changing with the times, because these new bands had managers and they were gigging, so, it was a different story. But the baby that was Island Records and the children that Island records had, as I mentioned to you, us, that team of people, we were close, we were very good friends. I forgot to mention Jimmy Miller, the producer who went out and produced the Rolling Stones, he was there. Jimmy Miller was producing Traffic at that time. I think Chris might have spoken to him about getting interested in producing Nirvana, but he didn’t think we were funky enough because Jimmy was a drummer as well, but he did play drums on a couple of tracks. If you have the box set or you can get it, there is an outtake of “Tiny Goddess”, he is playing drums on it and it’s like 10 times better that the original. Did I answer your question well?

Yes, perfectly. Please tell us a few words about the making of “Rainbow Chaser” (from “All of Us” -1968) which is the first British song featuring flanging (phasing) throughout the entire song.

Again, it’s fully orchestral. It was not our idea to have phasing, but when we made the demo, we made it at a place we used to write and record a little bit and we were using little instruments here and there. I had a xylophone, we had some harmonicas and we had put percussion things that we used to mix them up with maracas in a box, we recorded three harmonicas on top of each other and we were imitating brass sounds. We knew that it was going to be brass on this song, so, we put our version of brass on the demo, in a very simple but fairly creative way. That was the beauty of those days, because there were limitations, the studio were four tracks. Once they added another four, you had eight. The concept was always good when we did demos, but the magic happened when we went to see Syd Dale with “Rainbow Chaser” and we played him our demo and he obviously liked the song. We had a few routine sessions with him and he explained a few things he was gonna do: He was gonna put brass on, strings will be here, the girls’ voices, etc. When we recorded it in the studio, during the playback of one of the takes, the 2-inch tape became unleashed from the spool and it flew off. In the process of flying off the machine, the engineer couldn’t get out to stop it, it kept going (ed: he makes a dragging sound) : “ghhzzzghhzzzz” as the spool was unwinding.

This all happened at Pye studio #2 and the sound that was making was like an airplane taking off and everybody was panicking, but we looked at each other and Alex said to me: “Oh, that’s great sound. It’s incredible! What’s happening? Maybe we can ask the engineer if can rewind it and find it”. So, that’s what they did: They rewound it and when they were mixing it, they added it all. So, it’s an accident. I should say it’s a beautiful accident, because when you hear today something like that coming out of the radio or anywhere, even on small speakers, it’s so powerful. Whatever the effect was then, they didn’t do much to it, they added a bit compression and echo. Interestingly, on the box set, there is a version without the brass, because they went back to outtakes, it’s good but of course, once you have heard the brass version, you won’t forget it. But you know, like in life, there probably are some people who would say: “Oh, I heard the original version that you did without the phasing on the box set and I love it more”, because that’s how people are and that’s how people like Madfish are so successful with their box sets because they have customers like these.

I’d like to think that there was something that triggered that lyric that has to do with a man who did something or ran away from something. He was behind bars, he was in prison, but he wasn’t really guilty of anything. The woman protagonist was writing a letter to him saying things like “missing being with you” and “I see you in the orchard” where (ed: the recites the lyrics) : “Orchards smell of sweet perfume/ The mountainside is now in bloom/ And I am here waiting”. The tune had an Albinoni (ed: Italian baroque composer of the 18th century) influence, I think, because Alex and I had listened to quite a bit of baroque music of that time. Alex was brought up on a different culture than mine and maybe that’s what made the collaboration very interesting and different and we were able to develop something that was a bit unique. Alex came from a classical background and when he lived in Paris he was enjoying jazz. I came from Ireland where I grew up with some traditional music which is not far away from the bouzouki type of music in Greece, with mandolins and bouzoukis, these things, like The Chieftains, that was the music I loved once I heard it. I heard a lot of religious music in choirs, I heard a little bit of light opera that we used to do with school, but mostly what I heard was on the radio and it was rock ’n’ roll coming from America. Then, when I came to London I had that, and Alex brought in his background. I think what connected us was something that I found myself when I lived in Greece for a number of years. You know, Irish people were very connected to the earth, because of our history and our past and probably by our exploitation by everybody -except the Romans-, especially the English. We had famines, difficult times and we were isolated out there on the Atlantic. Greece has a series of islands and I found that people have in their blood that deep connection with their own landscape and earth. I had that feel in me but then I read Kazantzakis and once I read Kazantzakis I knew my feeling was good. Sorry to drift so far away from your question.

No, no, no! I love it! I think in my previous life -if any- I was Irish, because I have this rebellious mentality.

Well, there you are, I made any word that I said mean something to you. We, the Irish, are basically Celts, but the Celts came out of Europe and somewhere the paths crossed, I don’t know. I think it’s more ancient than that, it goes back to things like stone, water, earth, sounds, what you hear inside your mother’s womb before you were born. Of course, I found we used to be quite a matriarchal society, which Ireland was, as well. It’s not always a great thing, in the modern times, but it’s important. The rule of women, in whatever aspect, in Greece or in Ireland, it might have been subdued a little, in visibility and in what they were allowed to express. They still can quite powerful when they want to, as mothers especially. People learn more about this but they never go into the depth of it. You have your own stories: The son killing the father (ed: Oedipus).

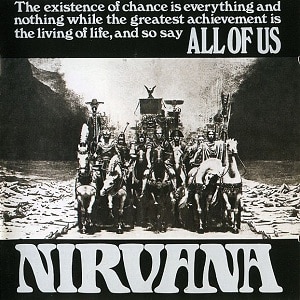

What is the meaning of the album cover of “All of Us” (1968)?

Quite simply, we had started writing the songs and we went to Germany to do a TV show called “Beat Club”, you can still find it today. For some reason or other, Alex didn’t make it. I don’t know whether he had fear of flying or anything else. Anyhow, we had a band for television shows and things that we did. We went to Beat Club, we did “Pentecost Hotel” and it was produced by a man called Michael Leckebusch, who became quite a fan. There was another film director called Horst Königstein. I don’t know if Leckebusch is still alive or not (ed: died in 2000), but he was older than us. I know he went out and had a good career in film. The band went back to their hotel somewhere, having a good time, but you could have a good time in a lot of places in those days. He suggested that I come to a small exhibition that he was having because he had directed a production of “Hamlet” in a small theatre and everything was black and white: He had two Hamlets, a white Hamlet and a black Hamlet, the stage was black and white, all the actors were black and white and the exhibition to go with it, was in that theatre.

Everybody thought: “Amazing cover” and nobody ever seemed to be bothered or had any implications in those days about the undertone and the messages that that could be sending, nor did I. In my ignorance, I just thought it was a magnificent photograph, but later I read up on Leni Riefenstahl and I found out who she was. Actually, I traced it -like many people did probably- to the film that was in and that’s the story. I think Leni Riefenstahl was having an affair with Goebbels or one of those people in that group. He was financing her to make mountaineering films, which she did a lot of, risking her own life all the time. She was pretty out there and in recent years she went down to Sudan and lived with the native people there (ed: Nuba people). They are very-very tall, everybody is over 6ft, but she lived with them for about two years and photographed their life and history and everything. Her most recent work, when she moved to America in her late 70s, she somehow managed to convince the authorities there that she would be able to swim under the water to take underwater photography. At that age, you have to get a license and she did and took amazing pictures of fish. What a woman!

Was “Christopher Lucifer” (from “Markos III” -1970) written for Chris Blackwell? Initially, I thought it was a kind a response to Pink Floyd’s “Lucifer Sam” (from “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” -1967).

No, it had nothing to do with Pink Floyd. Nothing whatsoever. I think you have to leave that to your imagination. I told you Chris Blackwell was a wonderful man but to do what he did with that label you have to take chances, you have to believe in yourself, you have to believe that you can be a winner and that requires a bit of a gambling instinct. So, we leave it at that. It’s a good song, although it’s not one of my favourites, but it’s a piece of social commentary of that time. That’s all: Creative social commentary.

Who were your influences when you formed Nirvana?

I told you I only brought what I knew. I was listening to mostly American music before. I was in a blues band before I met Alex called The Second Thoughts. I was in that band and of course that was influenced by Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Howlin’ Wolf, Mose Allison, all those people. So, I was bringing that. I had about 6 or 7 albums that I used to listen to. I had a Mose Allison album that I used to play all the time. I had a Frank Zappa album I liked, I had a Tim Buckley album I liked. I can’t remember all of them right now, but I had 6 or 7 albums that I listened to on rotation. Alex and I, our influences were more from within rather from without. Once we started making music, we very rarely listened to anybody else’s music.

Did you listen to Karlheinz Stockhausen like other bands of your era did?

Alex introduced me to that world: Experimental music, concrete music. I remember once we were talking about doing something on the piano when we were making one of our demos and the idea came up that we would put something on the inside of the strings of the piano, to change the sound a little bit. What we did was: We had an electric shaver and we put it inside and it was moving around on the strings and we recorded it. Alex said to me that this guy Stockhausen would be doing stuff like that and mentioned somebody else as well, Terry Riley. So, in a way, I didn’t know anything of that world of experimental, electronic, avant-garde music. I think Alex before I met him, he was listening a lot to The Jazz Messengers and Miles Davis, because he didn’t have any blues or American music background, he had a European background. He started his journey, really, when he went to Paris. What he heard in Greece wasn’t bouzouki music, it was more classical music he heard at this home.

Would you like to share with us the story about Salvador Dali during the French TV show “Improvisation on a Sunday Afternoon” in 1968?

Again, another TV show that we did in Paris and we went overnight. We drove down there, we went on a ferry and arrived there after a long journey. We were awake for a day or two. We had been recording and then we went somewhere to eat and we got a call. In Paris we didn’t know what to expect, there were no expectations and we were just told by the A&R man in Island Records who was approached by the French TV channel, TV1. The A&R person was Muff Winwood, Stevie’s (ed: Traffic, Blind Faith, Spencer Davis Group) brother and he said: “You must be there at 10 o’clock on Sunday morning”, that’s why we were driving down overnight, “and all you have to do is look psychedelic”. That’s all, that’s what we were told. This was with the original line up with Sylvia Schuster playing cello, Brian Henderson playing bass, Alex piano and I and then it happened. It was actually called a “happening”. The programme was every Sunday afternoon, the channel was open, whoever they brought in, the star attraction could either do the show for an hour or two hours, three hours, four hours. However much they wanted they could have that time up to 18:00 or 19:00 maybe when they had an evening programme.

So, I mean, Dali was rampant, he was improvising the whole thing. We were in a corner, there were drummers and flute players and there were all these different props around: Portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Mao (ed: Zedong) and JFK on the wall and a big crucifix of Christ in a purple gown on the Cross. There was also a picador from Spain on a horse with the spear, life size, made in beautiful silver and about 6 tables full of the most expensive chocolate sweets you could ever find, it must have cost a lot of money. Dali just made it happen. Of course, all the people that were there had been brought in like extras, from schools, models, film schools, they were all from that background. Good-looking women from the street, bars, cafes and don’t forget that we were in the charts at that time, so, that was the reason that we were hired because we had a record that was doing well and (ed: French singer) Françoise Hardy was doing “Tiny Goddess” from the second album, so, we had a profile there. In my book “Psychedelic Days” there is a whole chapter about the Dali happening. The week before, I think Jean-Paul Belmondo was there with Dali. So, it was diverse with all kinds of artists, but of course Dali was bizarre, if not mad.

Was it an interesting experience when your previous band Second Thoughts shared a bill with the Rolling Stones at the Ealing Jazz club?

We shared many evenings with them, we supported them at least 6 times. We were the resident support band because all of us lived in Ealing. It was called Ealing Jazz & Blues Club at that time. I remember that the guy who ran it was from Iran, Fery (ed: Asgari). The Stones played there, Alexis Korner who was responsible for making The Stones happen initially, because Alexis Korner introduced Brian Jones to Mick Jagger and Keith (ed: Richards) and that’s how they came about. Cyril Davies also used to play there, The Yardbirds… There was a series of venues around West London: Crawdaddy in Richmond, Ealing Jazz Club and then, some Saturday nights we supported the Stones and maybe there was somebody else on the bill as well. I think there was a band called The Tridents who were from Chiswick. Then, we got promoted and we were headlining there our shows, on a quieter night than Saturday and eventually we got asked to play at the Ken Coyler 51 Club (ed: Studio 51) in Great Newport Street in Leicester Square, which was a great blues venue and that’s where I saw The Pretty Things and The Downliners Sect for the first time, because they were doing the same as we were doing in Ealing. Being there with those people, we weren’t being starstruck or anything like that, because I knew the Rolling Stones were an amazing band, just because of the way they played. Even from the blues that I knew, they had really worked hard to find something original, because they had a piano player as well, Ian Stewart, who was their roadie. Of course, they were getting all the good piano sound licks with him that you could hear on the Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley and Howlin’ Wolf records. There, in that atmosphere, which was a small room underneath Ealing Broadway railway station, sweat poured off the wall because there were at least 300 people in the room, when it should only be 200, the band stuck in the corner and everybody was having fun with everybody else there. Regarding facilities, it meant very little. There was a facility there, but in my book I write about that and explain it, about washing harmonicas in there and things. We had a harmonica player in our band. To answer your question, it was one of those things that stay in your DNA forever.

You played with Chris Thomas (later engineer of The Beatles) in Second Thoughts and Hat and Tie.

Chris Thomas wasn’t in the band at that time. Then in the band there was a guy called Mickey Holmes and once we got a name around West Ealing and at Middlesex area, we had a weekly gig at the Ealing Town Hall and that’s where I first came across with Chris Thomas, because he was in the audience and he turned up in quite a few gigs. After one of them he came back to me and said: “If you ever need a bass player, contact me. I have a red Fender bass”. Then, as it happens Mickey Holmes was going through girlfriend problems, every band in those days seemed to have a person whose girlfriend often broke the band up and quite often it was the bass player. Drummers never seem to have that problem, drummers didn’t fall in love. That’s a good title for a book, isn’t it? “Drummers never fall in love”.

Did you feel a bit jealous when Chris Thomas became engineer of The Beatles (later he mixed Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon” and produced Sex Pistols’ “Never Mind the Bollocks”?

No, no, no. I came back from Sweden with The Second Thoughts, I had a totally different band that I took to Europe, to The Star Club (ed: in Hamburg) and places like that. I came back to Ealing, I wasn’t even well at that time, I got sick in Stockholm with the cold weather, the life and everything, and he told me that he had met his girlfriend now and of course you could see that she probably wanted him to settle down a bit more. He had written to EMI to see if he could get the job as a tape operator and learn something about production. I said: “Oh, I hope it works out, that would be really good” and then about a year later, he said to me: “I got the job. I’m going to be going to EMI. I’ve got to change my life”, because in those days when you worked at places like EMI, you had to wear a jacket and a tie. You couldn’t be turning up in hippie clothes. It was a very-very structured environment, almost run on an office level, even though we romanticize now Abbey Road. Even engineers used to wear white coats. No, I had no feelings like that. I made my choices, I was living my life and he was living he life. Things happened very quickly for him, I believe, because George Martin (ed: The Beatles producer) said to him: “Just watch everything for about 6 months. Don’t ask any questions, just sit at the desk with whichever would be” , i.e another engineer and I think that’s what he did. Eventually, as they’ve written about it- I haven’t seen Chris in many-many years- one night George Martin called and said: “I’m not coming in tonight” and Chris asked: “Well, who else is (ed: the person in charge) ?” and he was told: “Well, you are. You are taking over the session” and that was his first Beatles session. He told me, -at some point, maybe two or three years later at CBS Records- that he ended up that night playing harpsichord on “Piggies” (ed: from “The White Album” -1968), because when they found out that he was a piano player as well, they said: “Well, do that”. So, I think it was him and Geoff Emerick, the famous engineer. Then, Chris had found the band Climax Chicago Blues Band and he fell in love a bit with it and he produced a bunch of albums with them and then the rest is history. I don’t know where he is today. I think maybe he lives in Australia, I don’t know. I’m not in touch with him, I’m not in touch with that past life, I’m not in touch with Ealing and many of the people that I know of that era, have passed away. So, I’m very lucky to be alive. It feels like having lived three lives probably.

How emotional was it for you to write your autobiography “Psychedelic Days”?

How emotional was it for you to write your autobiography “Psychedelic Days”?

It was a pleasure. It’s not a biography, it’s capturing the period from ’65 to ’71. I called it “Psychedelic Days” because they were, in a way. “Psychedelic” means a lot more than some people think it means. I managed to weave into it and around it: Where I came from, how I was born, my growing up and then my travels. The travels were all linked to situations that had developed out of people I knew in Ireland. For instance, Alex and I had written a song for Jimmy Cliff and he was asked to perform it at the Rio de Janeiro Song Festival and there was only one ticket for the songwriter, a free ticket, all the expenses paid. I said to Alex: “We will toss a coin for it” and Alex said: “Not, at all. I think I’m going to go to Greece at this time” and I went. There is a chapter in the book about Rio de Janeiro with Jimmy Cliff, a chapter about Dali, a chapter about Mickie Most, the famous producer (ed: The Animals, Donovan, Jeff Beck Group), who produced “Wings of Love” with Herman’s Hermits (ed: from Nirvana’s “The Story of Simon Simopath” – it appears on “The Best of Herman’s Hermits Volume III” -1968). He was our neighbour upstairs, above Chris Blackwell, so, we saw a lot of him. He was probably one of the most well-known people who had been able to choose or find or hear a hit song and he’d know it straight away. He was a useful person to have around and very influential if he liked one of your songs; he wouldn’t do you any favours. We played him “Wings of Love” as a demo, before we recorded the main version and he said: “Oooh, I like that!” and then, in that week he called Chris Blackwell and said: “Tell the boys, if they are interested to come down tomorrow at De Lane Lea studios, I’m mixing their track with Herman (ed: Peter Noone -vocals, guitar) and the band” and we went. That was another experience, quite an amazing one because the circle goes around, because sitting in a chair in the studio -that was two sizes too small for him- was Herman’s Hermits manager, who went out and managed the Rolling Stones (ed: and The Beatles), Allen Klein.

Please describe to us your two meetings with Jimi Hendrix.

One meeting was in the recording studio when we were doing a show with him. We were doing “Pentecost Hotel” and in those days you had to re-record the song for television, you couldn’t do the original version. They wouldn’t duplicate the track that you have on the record. You had to start from scratch and spend a day in the BBC Studio, make it again, put your voice on again and then mime it on television. As we were doing that, Jimi Hendrix came through there and I had known Mitch Mitchell (ed: Jimi Hendrix Experience -drums) from the Ealing days because he was one of that crowd. He worked as a drummer salesman in Jim Marshall’s music shop and I knew Noel Redding, (ed: Jimi Hendrix Experience -bass) as Alex also did, because Noel Redding had played on a few demos for us, as a bass player. But when he went to audition for Hendrix, he said: “I don’t play bass but I’ll bring my guitar”. It was very fortuitous for him the way it happened. When Mitch saw me in this big studio, as they were walking through, we established a contact and Jimi Hendrix saw it and then he started looking at the cello player (ed: Sylvia Schuster) and the instrument. He sat down in front of her and he was looking at this and said: “What is this?” He hadn’t seen a cello in his life. He didn’t know what it was, as a musical instrument. Then, I saw him about a month later in the Bag O’ Nails club where musicians went and I met him with his manager, Chas Chandler (ed: bass) from The Animals and we connected a bit that night and not much longer after that, we went to his maker. I was there with Viv Prince, the drummer of The Pretty Things. I knew Viv but I never made any music with him. I knew Viv socially, I used to have a few maverick nights with him here and there every now and again.

Were you frustrated the first time you learned about the existence of the American Nirvana?

Not frustrated because when I first heard them on the radio, I thought they were just like an unknown punk band. Their record had been played in whatever station it was and I said to Alex about it and we said with naivety: “What’s this music? This is nothing” We didn’t think it would be heard again, so we just continued to do what we were doing until two months later. They were on television and they were promoting their hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. I happened so quickly; they were promoted from America so fast by Geffen. At that point we had to do something about it. We couldn’t be doing anything about it from England, they wouldn’t take us seriously and we knew we had to be taken seriously because we had recordings out, we had a good profile in Europe and some profile on America on a couple of hit albums, “Rainbow Chaser” was on the compilation “The British Invasion: The History Of British Rock, Vol. 9” (1991) on Polygram. That’s what we did, we went to America and we stayed there for quite a while with an American lawyer until we reached an amicable agreement. Both bands could use the word Nirvana, going forward and we mustn’t play grunge music -which by now had a name- and they must not play what our music was. We mustn’t impeach on each other’s sound, that’s the legal expression and that was it.

No. No, I think they were all rubbish. If I owned the word “concept”, I would have only one album and that was one of my favourite albums from the following year (ed: 1968). I didn’t realise that while we were making “Simon Simopath”, two brothers in America in Los Angeles were making their album, working very much the way we were. I didn’t know of them until I heard the album, somebody mentioned it to me because I like Love’s “Forever Changes” (1967). That was quite influential and progressive piece of work at that time and this album that I heard (ed: “Playback” -1968), it was by a group called The Appletree Theatre on Verve Records, which was part of the same label (ed: MGM Records) that The Velvet Underground were on and all those people. I loved that album and I still do till today.

Had you ever been to the UFO club?

I had never been to it. I never went there. I had no interest in Pink Floyd or the Soft Machine and I wasn’t doing LSD. I’m not saying that you had to use LSD to go to the UFO club but I wasn’t in that zone. As I told you, we did something totally different because we were outsiders, we weren’t London clubbers or going to The Roundhouse dressed as hippies. Alex had one or two places that he knew and liked to go and were good, where the social atmosphere was more European-orientated and there were many in London like that. We used to go to a couple of Greek restaurant that were very popular at the time. I would more likely go to somewhere like Ronnie Scott’s where I would be lucky to hear blues. I would hear to Mose Allison, for sure. Thodoris, we spent a lot of time working indoors, we didn’t have much time for going out after a gig, getting pissed, talking about how the gig went, hanging out with groupies and all that. We did hang out with some women, but I wasn’t in that scene and Alex wasn’t in that scene either. If we did do something, we only went out maybe once, maximum, maybe on Friday or Saturday night somewhere in London. The rest of the time we used to work, that’s how we managed to make three albums in 2 ½ years, good ones, as we can see now.

They are still out there and they are gathering new listeners as we speak. Of course, I continued as well, after Alex, when I did my solo work and Alex said to me: “If you want to continue with the name of Nirvana, use it” and he made sure that he is credited with his things. So, I went on and I made “Local Anaesthetic” (1971) which became quite a popular Nirvana album, but it’s totally different from anything he and I did together, but a lot of Nirvana fans liked it and still like it today. I have people calling it “prog”, I don’t know what it means. It was just me wanting to do something different and knowing that whatever we made and created with Alex and Nirvana, it was interesting but experimental because “Local Anaesthetic” is very experimental and that it would probably be ok. As it turned out, it’s in the box set and it suits beautifully, as does the next album, “Songs of Love and Praise” (1972), where I went back more to more melodic tunes and I re-recorded “Rainbow Chaser” and “Pentecost Hotel” in a different way, with a choir. On “Rainbow Chaser”, I put the tempo up and made it more jazzy on that album. Then, I made my first solo album called “Me and My Friend” (1974), which is rather strange, but fits the CD box set.

Alex and I were always in touch and something came about when we started talking about a musical we had started working on, at the time it was called “Blood”, later the title became “The Secrets of Soho”, then it became “Secrets of Soho” and then it became “Secrets”. We worked with a couple of script writers and eventually we started putting that together: We had the original tapes very well-recorded and of course this was a beautiful thing for the record company to have because “Secrets” has never been heard by many people until the vinyl release four years ago and now on CD. The reason the CD sells so well is because not everybody can afford a vinyl box set these days. You have to have money, they are not cheap. So, this is when you know you have a good record company behind you like Snapper/Madfish is. They do their research, they go out and make sure that there are enough people interested in this and they knew that because many people probably had written to them saying: “I’d love to have a CD. Would it ever come out on CD, because I couldn’t afford the box set?” and they probably thought: “Yeah, we can do this”. They just needed a little bit of time, like 5 years and here we are. Bravo to them, bravo to Alex, bravo to myself and God is good.

No, I had no reaction to it. I was never somebody who was listening to the latest sounds. I’ve read all about it. I knew The Beatles albums because you can’t escape them: They were on the radio, they were on this and they were on that, but I wouldn’t be invested in them. I wouldn’t be devoting my creative time or even my creative listening time to them. But when I heard eventually something like “Eleanor Rigby” (1966) and of course “Strawberry Fields Forever” (1967) and later the Lennon song, “Across the Universe” (1969), my ears picked them up and I thought: “Well, these guys are doing something amazing”, but other than that, no. In the interview I did very recently with this other magazine, said to me: “Were you influenced by The Zombies?” and he named their album “Odessey and Oracle” (1968) and I had to say to him: “Listen, I have never heard it. I have never heard that album”. I think I read too much.

In Jimi Hendrix’s music, in George Harrison’s music, in Santana’s music, there is also a very strong spiritual aspect. Is today’s music spiritual?

The instant answer is: “No, no, no”, but occasionally you‘ll hear something and you’ll think: “This is deeper. This is different”. I ‘m trying to give you an example, but there is very little that has any spiritual connection to it. How can you have spiritual connection when every fucker is using AI and all that nonsense?

Had you ever been mistaken for Leo Lyons, the bass player of Ten Years After?

No, never. I didn’t know them, but I knew of them. I had never been mistaken for anybody. A few people who look at the cover of the box set and the photographs by the famous photographer Gered Mankowitz, say that I look a little bit like Paul McCartney. Other than that, nobody has ever compared me to a lookalike.

From you era, I’m a huge fan of Scott Walker from The Walker Brothers. Did you get to know him?

Yes. I couldn’t say that I got to know him, but when I was recording “Local Anaesthetic” and “Songs of Love and Praise”, I was doing them at Phonogram Records in Bayswater Road, which is just at Marble Arch; not Pye, which was on the other side of the street, where we did the Nirvana records. Because a guy at Phonogram had offer me a deal to make a couple of albums, which I wasn’t ready to do at the time because I was going through some emotional problems, I had become a bit addicted to barbiturates and stuff and I just took a year out. That was after “Local Anaesthetic” I think. Then, he contacted me and said: “Maybe you would like to do something and we are starting a new label here called Vertigo. I knew you were with Island. Maybe you can help us out with a few things. Maybe you can bring here what you loved and you had with Chris Blackwell”. So, I went to see him and it was all pretty good and ok, but it was a totally different set up then, because Vertigo was just gonna be a couple of rooms and big offices at Phonogram, which they were Philips at that time. I said: “Give me 3 or 4 months and I will think about it”. So, I had some new songs and as opportunity he was giving me free time (ed: in the studio) and I started there. I was responsible for bringing a couple of bands to that label, but what interested me most was a music room there which was inhabited by a man called Johnny Franz.

He was a bit like you. He never played a concert after 1978, he was reclusive, he went out in London wearing a hoodie with a baseball cap, he didn’t do interviews, he was very shy, he spoke through his art.

On meeting him, it was of course a very casual working environment where Johnny Franz had this piano and Scott Walker was standing there and they both had a tea but not in mugs, they had their tea in proper cups and saucers, like proper English tea is served. Johnny Franz was so old school, so respected amongst the original variety music, jazz and orchestral music where everybody was using arrangers and of course he was attracted to Scott Walker’s voice and I’m sure Scott Walker was attracted to his arrangements. I only saw it, relaxed, sitting in the chair. Maybe I was in the room with them for half an hour, three or four times when they were preparing for an album. Johnny had said to me: “Any time you want, just come in, sit around and you’d enjoy it”. He (ed: Scott Walker) was like every other person who has those certain inhibitions about things. Once he is in a safe environment, he can change and he can become smiley, which is what I remember of him now, if I think about that moment. He was very happy, smiling.

Did you get to know other people like Steve Marriott (Small Faces, Humble Pie -vocals, guitar) or Marc Bolan (T.Rex -vocals, guitars) ?

No. I said to you we were not part of any scene, so I would‘ve never been going to the places they were hanging out like The Speakeasy Club. I am not saying I never went to The Speakeasy, I wouldn’t be going there on a regular night. There were hangouts if you were in that whole ‘60s atmosphere. I think you have to understand that both Alex and I felt a little be like outsiders and that made us different, made us work harder and come up with something that was original. We weren’t just a band that was going to do gigging and have to make it on the road, I doubt if we would have survived it, actually. We chose the right choice when we were offered it. You ‘d see people all the time during that era. Once that era passed, I moved abroad, I lived in Spain and Germany and eventually I went back to London. Then, Alex moved back from London to Greece, when his mother was sick about 50 years ago. Of course, Alex and I got very close again during the years I‘ve lived there; I’ve lived there for 12 years, although he was living at the center of the city and I was living in the northern suburbs, but we’d see each other a lot, I’d just meet him. We ended up working on old songs that people needed for compilations. We resurrected a few of them, there was a songwriters album that came out called “Yesterday’s Sunshine Today” (2020) with all these different bands recording Nirvana songs. There was a Greek band there that recorded one of our songs (ed: “Wings of Love”) called Echo Train. I was working with Alex quite a bit and we did a totally new version of “St. John’s Wood Affair” from “All of Us” for a modern-type trippy psychedelic cover album.

Yeah, as long as there is vinyl and there is a way for it to be heard. I think CD seems to be surviving, I don’t know if sales globally are better than they were… Modern bands have taken a new angle on ‘60s psychedelic music, if you see what I mean and they just deconstructed the compositions and made them into a new format of songwriting and they give credits, they say: “Oh, this is probably influenced by things I’ve heard from the ‘60s etc”. I’ll give you an example of a band who do that because they come from my country, they are called Fontaines D.C. Maybe psychedelia would live through a band like that, I don’t know. There are so many interpretations of what “psychedelic” is and it depends on what interpretations of psychedelic mean to you or me. It’s different how it would survive in this new deconstructed world of everything, whether everything is going back to the beginning or it’s being plagiarized or it’s being stolen. I mean, AI is stealing the craft of songwriting, especially whatever has been psychedelic as a word. So, I can’t say I’m optimistic, but I can only say I was there, I knew it, I lived it and I hope for psychedelic music the show will go on.

Thank you very much for your time. I enjoy talking with people from your era. I like to learn about the creative process etc.

Yeah, that’s one of the reasons I wrote the book “Psychedelic Days”. I didn’t have an intention of writing it, but one of my brother’s three daughters said to me: “What was it like being in the ‘60s?” and then I was explaining to her and her sister said to her: “Ask Patrick if he would write a book about it” and that’s how it started. I thought: “Yeah, maybe I will”. So, when I moved to Spain first, I was living outside Granada, in the mountains, in a very small village, very quiet, isolated and I started the book there and I wrote it in about six months without too much pressure. It’s quite straightforward, it’s not a book of genius but the people bought it and they have liked it and got some very good reviews. It’s fun, it’s not a serious book, that’s why it’s real. It’s not meant to be heavy with details; it’s for those who weren’t there.

Nirvana photos: Gered Mankowitz

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Patrick Campbell-Lyons for his time. I should also thank Keith James for his valuable help.

Order “Nirvana – The Story Must Go On” box set here: https://burningshed.com/nirvana_the-show-must-go-on_boxset

Order Patrick Campbell-Lyons’ book “Psychedelic Days” here