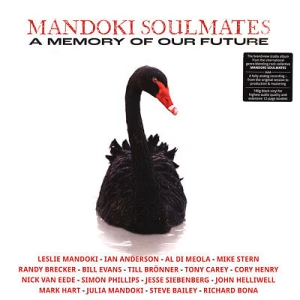

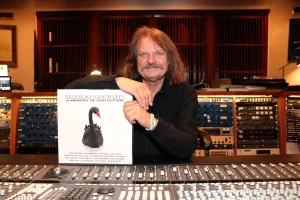

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: October 2024. We had the great honour to talk with a very talented musician and a fine person: Leslie Mandoki. He is best known as the songwriter, drummer, singer, lyricist and producer of Mandoki Soulmates for more than 30 years. In May they released their latest studio album called “A Memory of Our Future” featuring Ian Anderson, Mike Stern, Al Di Meola, Randy Brecker, Bill Evans, Simon Phillips and others. Also, in the late ‘70s he was a member of disco group Dschinghis Khan, performing with them at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1979. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

Could you please give us some basic information about the concept of “A Memory of Our Future” album?

Could you please give us some basic information about the concept of “A Memory of Our Future” album?

Well, the whole world is into crisis. We have wars and various crises and I felt the need inside me, in my heart, to write an album about this situation that it seems to me that we lost the compass to get out of these multiple crises. Musically, it merged the British prog rock values of the old times, in a new way, in a fresh, younger way, with the American jazz rock virtuosity. I felt very strongly this need to go back and speak in a way we spoke years ago, but in a fresh, new, modern way, that’s why record in analog and we play together and this is a handwritten love letter to our audience and not just another digital recording, where we are focusing on the post-production of it. We thought: “Ok, now we are going to focus on the recording again”. So, it was very crucial for me to do it this way. The message for humanity against this division is to build bridges again and that music is the greatest unifier. That’s our message.

All the musicians who play -once again- on “A Memory of Our Future” album such as Ian Anderson, Mike Stern, Al Di Meola and Randy Brecker are bandleaders in their own right. How hard was it for them to accept their role in this album?

I mean, we are playing together for about 31 years, in the meantime, so, it is always a great gathering and there is no pressure about it. We have a great feel together and we are a band. So, it’s not about accepting their role; this is a band of bandleaders. So, it is very natural to have this situation where everybody is playing their role and they are embracing the entire production. And of course this is for everyone. It is wonderful to have on the other instruments and the other roles on the album such experts, in many ways. So, it is fantastic for Al Di Meola (ed: Return to Forever -guitar) to play with Mike Stern (ed: Miles Davis -guitar) and for Mike Stern to play with Al Di Meola or Randy Brecker (ed: Brecker Brothers, Blood Sweat & Tears -trumpet) with Till Brönner (trumpet) or John Helliwell (Supertramp) and Bill Evans (Miles Davis) on saxophone. These are just fantastic people.

All musicians recorded in the same room in your studio. How much different is the end result instead of using filesharing?

It is totally different, in three different ways. One is, normally today you are sending files, it’s easy to do so, but when you get together and you see each other and feel each other, you breathe the same air, you have a lunch together and you have a dinner together, being together is a different ball game. It is a totally different attitude because the atmosphere is different. In this collective improvisation that we do, we are looking each other and we are feeling each other, it is very strong. So this is one of the three things. The other aspect is the sonic resolution. Sonically, it sounds much better because analog is 60 years old, year by year, you are just pushing it up and up and up… Of course, digital way to work is much easier and simpler. Let me give you an example: You have endless possibilities to record guitar solos, the tracks are unlimited, but we had only one track (ed: in analog recording). So, limitation can be inspiration and it is. I was very-very impressed by the way it came together; everybody was sitting in the same room and we were playing together. I would say to you that it is like a handwritten love letter to our audience. It’s not like a text message, it’s just different. We really had a very joyful time and the basic difference is that you cannot repeat anything, so, we gave our audience something naked, something that is how it was. So, that’s why we are extremely happy about the result.

How challenging was it for you to write the flute parts that Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull) played on “Blood in the Water”?

How challenging was it for you to write the flute parts that Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull) played on “Blood in the Water”?

Ian and me, we are working together for 30 years, so it was fantastic to write stuff having him in mind. Ian Anderson played like he was 25 years old. He sounds like he is fresh, young and full of energy. I mean, that was at full power and a great sensation.

I like “Enigma of Reason” which is a very ambitious composition. Please tell us a few words about this.

I only recorded for this album the most important songs that I wrote in the last period of time, but “Enigma of Reason” is the heart of the album. It was the first song that I wrote for this. It represents pretty much everything that this album is trying to say about the reasons why the whole world turned to be a mess and everything is upside down and we should try to get out of this crisis and really move forward and feel that all the values that the generation of Woodstock was teaching us are more than valid now. We should remember how important music was and how much music was a great unifier.

The vocals of Julia Mandoki (Leslie’s daughter) in “The Big Quit” are fantastic. Why did you choose to put female vocals in this song?

I didn’t choose. My daughter was just walking in and I said: “I had an idea. Let me record it”, so I recorded her. It was sounding so fantastic that I said: “It’s looking great!” and that’s the way we did it.

In “Devil’s Encyclopedia” you write “the social media becomes the devil’s encyclopedia”. Could you please explain it to us?

In “Devil’s Encyclopedia” you write “the social media becomes the devil’s encyclopedia”. Could you please explain it to us?

Yes, social media is amplifying the aggression. We all have in our hearts, sometimes, some anger and disappointment, but social media is transporting all the negative aspects in a very fast way and it is amplifying them. I think that is wrong because someone who is representing an opposite opinion than mine, it is not my enemy. It’s just a guy who has a totally different opinion and there is nothing wrong with that, so, let’s discuss and try to achieve something. This is really important. It’s so important to breathe together. The message is that music is the greatest unifier, it brings us together. That’s what I had in my mind. That is what this album is all about. “The Memory of Our Future” musically, of course, is fantastic. In a song like “Enigma of Reason” you can also involve Richard Bona’s (ed: Joe Zawinul, Pat Metheny -bass) genius playing and it was just fantastic.

You grew up in Communist Hungary. What were your dreams when you were looking at the postcard you mention in “Matchbox Racing”?

Oh yeah! Thank you so much for the question, it’s very nice. Well, I always said: “I am going to make it. I am going to make this dream come true. These are the bad days in my life. I have to leave Communism behind me” and as my father said on his deathbed I have to go and live my dreams and not dream my life. That’s what I was told and I did it.

The instrumental “Melting Pot” which closes the album is very atmospheric. What inspired you to write this?

This was funny because a song like “Matchbox Racing” was born in a very classic way. I remembered this postcard of this big parking lot in LA and everybody said back then when we lived under Communism: “You will never ever see Los Angeles in your life”. So, I was remembering what my father said: “Boy, live your dreams and not dream your life” and I just wrote down what life was giving me. So, “Matchbox Racing” is one of these typical songs where I am saying: “I wasn’t really writing it, I was just writing it down. Life was offering me that story and life was offering me the music. I am in the fortunate situation that I ‘m writing it down” and this is so great. But “Melting Pot” is a totally different situation because we had recorded the whole album, so, we had finished and we said: “Ok, we ‘ll make a double album and we just have a little space on it”. It made a 80-minute CD. I don’t remember who asked me, but one of the guys said: “Do you have one more tune?” and I said: “Well, I have a theme, I have a melody”. So, I played the melody and then we just improvised our own bits. It is hard to say that I wrote it, because I wrote the melody. The composition was about, let’s say, 12 bars and everything was unfolding together in the room and I thought: “Ok. Let me share it with the audience”, because it is something very special.

Why did you decide to record “A Memory of Our Future” in analog equipment?

Why did you decide to record “A Memory of Our Future” in analog equipment?

Well, we were on the road on our 30th anniversary and it was a situation where you go out and play big venues and open air concerts and people love it and you have encores and everything goes on and on. You keep writing and you don’t see in the calendar any space of months to record and send files back and forth. One of the guys, probably it was Al Di Meola who just asked me: “Do you still have all the old analog machines in you cellar?” and I said: “Yeah, of course” because we were not using them for 20 years. So, I came home from the tour and I just checked the machines and I called my old sound engineer who has retired and we checked the old machines how they were doing and they were doing fine. We had to change a couple of little things, I suppose it took two days of maintenance and then I called everyone. I said: “Guys, what about to find two weeks?” We recorded the album in two weeks in analog and that was it. It was fantastic, it was such a great moment of life! It was perfect and I loved it.

What is the meaning of the black swan on the cover of “A Memory of Our Future”?

Of course the meaning is the togetherness. We all have read all those books about the black swan and the most important message is that the black swan is here, we feel it around the world -maybe not in sunny Greece- but you know what I mean, people are dying in wars. What we are trying to say is: When someone is listening to this album, 80 minutes long and not taking their iPhone in the hands and they are just listening to the album, maybe they are taking the booklet and they are reading the lyrics and they are listening to it, then the black swan is going to be white again. So, this is what I am saying in my concerts: “Look, on my drums you see the black swan, but when this is finished after 3 ½ hours of concert the black swan is going to be white again”.

How did you come up with the idea to make “Hungarian Pictures” (2019) album based on Bela Bartok’s music?

How did you come up with the idea to make “Hungarian Pictures” (2019) album based on Bela Bartok’s music?

We were on the road about 22 years ago with this line up: Peter Frampton was on the guitar, Jack Bruce (Cream) on bass, Jon Lord of Deep Purple was on Hammond, Greg Lake (vocals, bass) of Emerson, Lake & Palmer was with us, Ian Anderson of course, Bobby Kimball (vocals) of Toto and Chris Thompson (vocals) of Manfred Mann and I played the drums. So, during this tour Greg Lake said at the soundcheck: “Look, after the gig, why don’t we sit together with Jon Lord, you and me, just at the end of the table and we have something to talk about?” He said: “Do you remember Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s wonderful “Allegro Barbaro” (ed: Bela Bartok’s piece – titled as “The Barbarian” on their debut in 1970) ? I said: “Yes, of course” and he said: “Well, the big rock ‘n’ roll secret, the story behind the story is that we actually didn’t want to do “Pictures at an Exhibition” (ed: by Mussorgsky, ELP recorded it live in 1971), but “Hungarian Pictures” (ed: by Bela Bartok), but we never got the rights to do so. But Leslie, we were born Hungarian, so, why don’t you just try to get the rights from the family of Bela Bartok. So, I was self-confident and I was stretching myself and I said: “Ok, I’ll take care of it”, but I couldn’t. I was reaching out for these folks, the Bartok family and they said: “No”.

But because I was so positive that I will get the license possibility we started to do it in London with Jack Bruce, Greg Lake and Jon Lord, the giants of Cream, Emerson, Lake & Palmer and Deep Purple and we were thinking of which parts we were going to do and the result was: We thought that it was gonna be such a great and big album that we said: “We have to do it right now”. Again, I begged for a second time the Bela Bartok family and they said again: “No”, so we couldn’t do it. And very unfortunately, Jack Bruce, Jon Lord and Greg Lake, all of them, passed away, they are playing now with Jimi Hendrix in heaven, but I kept my promise when the 70 years were over (ed: 70 years after the death of an artist, everybody can use his/her art without license) I sat down and I went to do it. So, I put out the files and these written sheets and I sat down with Al Di Meola, Cory Henry (ed: Bruce Springsteen -piano, Hammond, vocals) and Richard Bona and we just had a fantastic time and we knew that we had to do that. It is the heritage of Greg Lake of Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Jon Lord of Deep Purple and Jack Bruce of Cream, all members who passed away.

Considering the fact that you grew up in a Communist country is it a bit surreal for you to work with musicians like Jack Bruce (Cream -bass, vocals), Ian Anderson, Al Di Meola and others?

Yes, indeed, it is surreal. I ‘m surprised with your expression “surreal” because it is a very human expression. I will tell you the real story. I had this dream, I escaped Communism and got into a refugee camp in Germany and the American resettlement officer asked me: “What the hell are you going to do here, in the West, in the Free World?” and I said: “Well, I am going to play with Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull, Al Di Meola and Jack Bruce of Cream”. It was in ’75 and they were just in the peak of their career and the resettlement officer said: “You must be totally crazy, boy!” Next to me, was a very close friend of mine, Gábor Csupó, he was a cartoonist, he was creating great cartoon videos and the resettlement officer said to him: “What the hell are going to do, man, when you friend, Leslie, he is so crazy to talk about Ian Anderson, Al Di Meola and Jack Bruce?” and he said: “Well, I ‘m going to go to Hollywood and I want to found a new cartoon studio”. So, his first works were The Simpsons and Rugrats, two stars in the Hollywood world. The question is back to you: “Is it crazy to believe in things like that?” Yes, it is crazy but we made it happen.

You are from Hungary and you live in Germany since 1975. How difficult is it for you to write lyrics in English?

I mean, English is my first language so it was always my literature language and being a musician, of course, English was my first language. When I came to Germany, I started speaking German but English was always the language of rock and it was also very natural and organic in the way it was going.

I am a huge Jack Bruce fan. What memories do you have from your collaboration with him on all the previous Mandoki Soulmates albums?

Well, Jack (laughs). Once we were recording together, I think it was our second album (ed: “People in Room No.8” -1997) and I was recording it with Jack and Bobby Kimball of Toto and others. Bobby was out there and he is a fantastic singer. It was the song: “Let the Music Show You the Way” (ed: his sings the title) and there is a middle 8 that is very-very high, an expressive moment in my composition and lyrics and Bobby was singing it fantastically; he was the best singer in the world, he was in Toto. Jack was sitting next to me and he said: “Leslie, it is really good with Bobby, but let me do that with conviction, with a bit more emotion” and it was so fantastic the way Bobby Kimball was singing it and we thought Jack was a little egomaniac, but it was ok. So, Jack went out and Bobby was sitting next to me and Jack was singing it and it was blowing us away, it was exactly as what he said! Bobby was 100% and all of a sudden Jack was giving us a 200% track. It was just fantastic! It was so special and of course on the record is Jack’s version. I mean, we had a million great stories. Jack was a fantastic person, I loved his personality and his humour. He was very good.

How emotional was it for you to attend the funeral of Jack Bruce with Eric Clapton in 2014?

It was very emotional. Absolutely. His loss was tremendous and it was extremely emotional. I am still in touch with his children and his wife. Of course, absolutely.

Were you surprised when Quincy Jones (Michael Jackson, George Benson producer) called you at Jack Bruce’s funeral ?

Were you surprised when Quincy Jones (Michael Jackson, George Benson producer) called you at Jack Bruce’s funeral ?

Yeah, it was late night in London and he said: “I am going to introduce you in four days in New York to Richard Bona (bass)” and it was fantastic to meet Richard and that’s the way our lives goes on.

How much artistic freedom did you have as the bandleader of JAM in Communist Hungary in the ‘70s?

I didn’t have any freedom as a bandleader. That’s the reason why I really left the country. There was serious oppression, absolutely, so I couldn’t stay there longer. I couldn’t bear with this oppression. I had to find my way.

How much has your approach to songwriting changed over the years?

I think it hasn’t changed so much. Earlier, I was sitting more in the instrument to write. Today, I’m going with my canoe, I’m staying by the border in a waterfront house and I ‘m living with my canoe and I’m enjoying it and it’s just wonderful. Sometimes, I am just walking and the whole concept of the words and the melody is already created in my mind. Then, I sit down and I just control it and put the things in their right place (laughs). But so far, it has changed many-many times. I have the feeling that life is giving me the chance to write down something. I see something like “The Last Days of Summer” (ed: from “Soulmates” -2002) or “The Wanderer” or “I Am Because You Are” (ed: both from “A Memory of Our Future”), these are very autobiographical songs that they just happened around me and I wrote them down, because I saw these things happening around.

Who are your influences as songwriter?

Who are your influences as songwriter?

Actually, there are a lot of great songwriters out there, but most in the classical music. Everyone; from John Lennon and Paul McCartney to Frank Zappa and all the great prog rock writers like Ian Anderson. Also, I love the lyrics of Paul Simon and Al Jarreau. Actually, I don’t have a real favourite. I have favourite players and musical leaders like Ian Anderson, ok, he is the greatest or Al Di Meola, Mike Stern and Steve Lukather, they are my favourite guitar players. Or I love to listen to Jack Bruce and Richard Bona, but this is what it is.

You are a singing drummer. Do you like Levon Helm of the Band?

Of course. Singing drummers, we are not many. My dear friend Phil Collins is also a singing drummer.

Are there any concept albums that served as role models for “A Memory of Our Future”?

No, it was just very organically grown. It is very natural the way it is.

Was it an interesting experience to work with Phil Collins in “Tarzan” (1999) and “Brother Bear” (2003) films?

Of course! I mean, he is a great-great-great musician. A wonderful person. We had great times together and we enjoyed it a lot. Everything was fantastic.

Did you feel comfortable playing disco with Dschinghis Khan in the late ‘70s?

No. Not at all (laughs). I’m laughing today about this period of time and I say: “Ok, I could have enjoyed it”, but I wasn’t enjoying it. So, I was not really enjoying it. But back then was back then and it was such a long time ago. It was ’79, it was such a long period of time ago. We don’t need to look back, musicians should always look forward. That’s the thing.

Did you have fun performing at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1979 with Dschinghis Khan?

Did you have fun performing at the Eurovision Song Contest in 1979 with Dschinghis Khan?

It wasn’t so much fun. I was doing what I had to do but it wasn’t so much fun. You know, I was a refugee and this was a great chance and it was ok. But I ‘m a rock musician, so I was the wrong guy then.

Do you think popular music that was written in the ‘60s and ‘70s is much better than today’s music?

I wouldn’t say that it was much better but we had better chances to be creative. But nowadays the new generation has also great chances to be creative because they can do everything digitally at home and they are not depending on studios, labels, managements and all these. I mean, the creativity of the second half of the ‘60s and the first half of the ‘70s was tremendous and the labels were just supporting creativity, they were supporting being different and everything was not uniform. It was a great time and very inspirational. But I would say that today there are so many great players out there but they have a much greater difficulty to build their legacy because there are so many uploads on all the digital platforms.

Tony Williams (drums) joined Miles Davis when he was 17 years old. Are there those kinds of opportunities nowadays?

Of course, but because of the digital revolution you won’t realize those genius moments, but there are few leaders. There are so big talents out there, but they don’t have that opportunity, that simple and effective way of joining Miles Davis. I got all the support in my early years by Klaus Doldinger (saxophone), there aren’t these situations anymore.

Do you have any musical ambitions left?

Of course. Everything should go on like that.

Are you optimistic about the future of progressive music?

Are you optimistic about the future of progressive music?

Of course, because we are giving to so many questions, great answers.

Is there any newer progressive band or artist that you like?

There are lots of them. I wouldn’t point out one but there are a lot, of course.

Do you think because of the streaming services listening to an album from start to finish has now become a kind of lost art?

Yeah, this is a problem and not only that but also this gear (ed: he shows a mobile phone on Zoom) is a problem, because people now are listening to music but the same time they are answering a Facebook message. The attention span is just shorter, that’s why it is important to go back to the point that we enjoy listening to a whole album.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Leslie Mandoki for his time. I should also thank Mr. Chip Ruggieri for his valuable help.

Official Mandoki Soulmates website: https://mandoki-soulmates.com/

Official Mandoki Soulmates Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/mandoki.soulmates