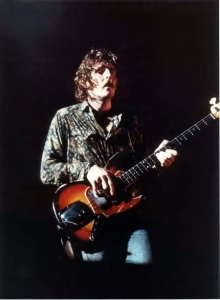

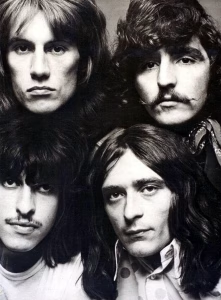

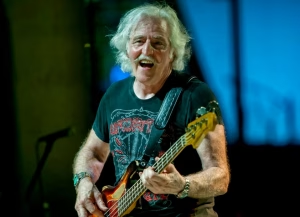

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: May 2024: We had the great honour to talk with a legendary bassist: Leo Lyons. He is a best known as a member of Ten Years After until 2014, having releasing several classic albums with them, such as “Ssssh” (1969) and “A Space in Time” (1971). Also, while in Ten Years After he performed at the Woodstock Festival in 1969 and the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970. As a producer produced albums for UFO and other artists. His current band Hundred Seventy Split released their latest studio album, “Movin’ On”, in 2023. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

What is the concept behind the formation of Hundred Seventy Split?

What is the concept behind the formation of Hundred Seventy Split?

Well, first of all, the name is a road junction in Nashville, where I used to live and we actually recorded the first album (ed: “The World Won’t Stop” -2010) there. I live in Wales now but I did live in Nashville. It was a side project, really, that Joe (ed: Gooch -guitar, vocals) and I started, to do something slightly different from the Ten Years After. We were in Ten Years After at the time and it was somewhat restrictive working within the framework of Ten Years After, so, we started the side project. Basically what happened was: Sadly, the other guys in Ten Years After weren’t happy with this, so in the end we had to leave and do it, take it up as a full time job, if you like (laughs). I think there are 6 or 7 albums in there, yeah.

Could you please give us some general information about the latest Hundred Seventy Split album, “Movin’ On” (2023)?

Yes, there was some delay in putting it out, some administrative problems, I don’t know what it was, but it is actually available now worldwide. Personally, I don’t have a copy (laughs), but I think I can remember making it. Yeah, I think it’s our seventh album. We tried to record it as organically as possible, you know, all in the same room, all at the same time and then if there were any mistakes, maybe we would pick them up. I don’t like recording one instrument at a time, I think it has to be organically, you have to get the energy and feel of live playing. I think quite a few people have started to think about that now, but it went from doing that in the early days to: “I do the drums and then you put the bass on”. It doesn’t work for me. So, it was fun. We wanted it to be fun. I wanted to do it as quickly as possible and we did. From what I know, is doing really well.

I really like “Sounded Like a Train” from “Movin’ On” album. Please tell us a few words about this nice song.

That was co-written with a good friend of mine, Fred Koller, along with Joe Gooch and it was really about the hurricane that came through Nashville a few years ago, that both Fred and I had an experience of. So, that’s what it is. You can put what you like into it, but that’s basically how it started. It could be a love song too, of course. Falling in love sometimes is like a storm having hit your life. But yeah, it was about the Nashville hurricane.

What makes the music of Ten Years After still relevant in 2024?

What makes the music of Ten Years After still relevant in 2024?

That’s a good question. I think a lot of our original fans have grandchildren that they play the music to. There is a lot of interest now by young people in what it was like then and although maybe I sound like an old person, I think they were better times (laughs). I don’t think the world is getting a better place and there’s a lot of nostalgia about those days. That’s what young people say to me: “Wow! I wish I ‘ve been there”, “what was Woodstock like to play?” or “did you know Jimi Hendrix?”, you know, all those questions that I get often.

I’ll ask you.

(Laughs) Oh, yeah, of course. What can you do, but asking. So, that’s why I think it’s popular. It only requires -for not just Ten Years After but that type of music- for people to hear it and I think then a certain number of people would say: “Well, I didn’t realise there was music like this” and I do get emails from fans like that. “I just heard your music being played in a movie” -for example- “and that made me look at the catalogue and now I’m a big fan and I ‘ve been buying all your records”. There is still a fanbase about there but the media calls the tune on pop music and it’s difficult to get it through sometimes.

What memories do you have from Woodstock Festival in 1969?

It was just one festival in many. We played the Newport Jazz Festival on the same tour and the Texas International Blues Festival, so there were many festivals that we were playing. The strange thing about Woodstock was, in many ways, that more people came than were expected. It became a bit of a disaster logistically for the people who ran it and then it was made into a movie, so that’s what made that stand out from all the other festivals that we played. The film (ed: “Woodstock” -1970) of course got that message over to people worldwide, not just in Free Europe but all over the Communist Europe and so on. It was a beacon of freedom, I think and that’s what made it so popular. There were 500.000 people, but to me, it was like playing another festival, which I always enjoy. I enjoy festivals more than anything but it was just another festival until the aftermath: The disaster, the rain, the storm and of course the movie that people made it something special. I don’t think you can replicate that again, it was a one-off thing that happen and I was very fortunate to be there.

How helpful was “Woodstock” (1970) film to the success of Ten Years After?

How helpful was “Woodstock” (1970) film to the success of Ten Years After?

Let me just say, I think we had a couple of chart albums prior to Woodstock and we were playing to 5.000-10.000 people a night, maybe. Then, all of a sudden we were playing to 50.000 people a night and what we have now, 50 years on: People still remember Ten Years After from Woodstock or at least they remember Woodstock and it wouldn’t sustain the living for that long, I would say, without the movie and the whole promotion. I don’t think a lot of those Woodstock bands would have been remembered. So, it’s been very beneficial. We are very-very lucky.

Were you surprised with the commercial success of “Love Like a Man” (from “Cricklewood Green” -1970) single?

It wasn’t as much a success in America as in the UK. I mean, I don’t think it charted in America (ed: it reached #98 in the Billboard Hot 100). “I‘d Love to Change the World” (ed: from “A Space In Time” -1971) was a big success, but “Love Like a Man” was the only single really that we had in the UK. The UK was very pop music-orientated. There was a television programme called Top of the Pops, you had to go on television, but for whatever reason we didn’t want to do the television show, so we didn’t do the television show, so they stopped playing our song after that, but it got to #10 and it charted in other countries, maybe France and different places. But we weren’t really a singles’ band, we were what they call an “underground band”, a band that didn’t like pop music and wasn’t very popular with the music press of the time, except the underground newspapers. It was quite a surprise for us, as was “I‘d Love to Change the World”, of course.

Was Alvin Lee (guitar, vocals) an easy-going person to work with?

He was like a brother to me and in many ways, we argued. Alvin and I worked together since he was 15 and I was 16. We strived for nine years to get a success and when we started to get a success, Alvin, for whatever reason, he didn’t really want it. In fact, it was so insistent that he didn’t want it. Actually, at the height of our success, we took a year off and didn’t work. So, in many ways, it was frustrating because I was enjoying -not the success but- the opportunity to play all the places that I never even dreamed of going, all over the world. But in many ways it was a bit difficult to work with; the things that he didn’t want to do: He didn’t want a hit single, he didn’t want to go to Australia or he didn’t like playing in Japan, he didn’t want to do too many American tours and eventually he didn’t really want to work that much (laughs). But that said, he was like a brother to me. I mean, without him and without me, I don’t think we would have had the success that we had. We were complimentary to each other, I think.

What was the greatest skill that Alvin Lee had?

What was the greatest skill that Alvin Lee had?

I think he could listen to a piece of music and play it. He was an innovative player, and in fact, if you are familiar with the music, there was a lot of jamming. We never really rehearsed, we were just playing off the top of our heads. When we went into the studio, we had the bases of a song and then we would just jam it out, which is why I came in with a lot of the riffs. One of the greatest things that he had too was that he had a great stage presence, a tremendous stage presence. Probably -I don’t know, it’s difficult to say and maybe I don’t want to- one of best stage presences on the guitar and vocals, I would say. Maybe there are one or two. I don’t know. Hendrix maybe. Rory Gallagher. A lot of the guitar players just sing and play, but Alvin was a showman, too. It was high energy music, that was what we did. We literally played until we dropped.

Was it an interesting experience to play at the Star-Club in Hamburg in 1962?

Yes-yes! Had we not played the Star-Club Hamburg I didn’t think our career would have developed the way it was because -not just for Ten Years After but for a lot of bands- you were playing around 5 or 6 hours a night, you were having to extend your set and the songs. It was a training period, really. Very-very important, for The Beatles obviously and lots of other bands. Suddenly, Ten Years After, we went back from playing in Germany to be a much tighter, a much better band with the ability to make a 3-minute song into a 20-minute song. For better or worse I think in some cases (laughs), but yeah, we were able to do that. It was our highlight.

How much different was the Ten Years After performance at Newport Jazz Festival in 1969 compared with the Woodstock one?

I think it was pretty much the same. I’m not sure, I think the reaction was good, but it was a most unusual thing to be one of the first rock bands to play that festival, which was folk and jazz, as you probably know. But as far as I can recall, it was the same. We played during the day there. It wasn’t quite as dramatic because there was no thunderstorm, no flooding, no fires. I don’t think there were 500.000 people there all covered in mud, so that was different, but it was great. I mean, it was probably a dream of mine to play Newport because I knew about the Newport Jazz Festival and one of my big heroes was Muddy Waters; I actually had the “Muddy Waters at Newport 1960” album. So, it was kind of a favour when I got to play Newport. Woodstock was a non quantity as I said, it was just another festival; it was one-off. But Newport was prestigious at the time for us to be invited to play there and I enjoyed it. I mean, one thing I do recall is my amplifier blew up halfway through which exploded a little bit (laughs), but otherwise it was great. We went on the road after Newport, we played three or four shows with some of the other Newport acts like Nina Simone and Dizzy Gillespie. So, it continued for a little while.

Is it true that Jimi Hendrix asked you to join his band as a bass player?

Is it true that Jimi Hendrix asked you to join his band as a bass player?

Yes, when we met. When Jimi first came to London, I went to see the Rory Gallagher band, they were called Taste at the time and I ran into Jimi and Chas Chandler (ed: The Animals -bass), who was managing him at the time and they were looking for a bass player and Chas said: “Would you be interested in doing it?” But I had put so much time into Ten Years After, say, almost 9 years, I decided to stay where I was, so, I didn’t take it. Noel (ed: Redding) took the job. I didn’t know Noel; he was actually a guitar player. But I had played with Mitch (ed: Mitchell -The Jimi Hendrix Experience drummer) a few times and Jimi had played with my bass a few times. We got him to play bass because he was a left-handed, it was easy for him to play bass, he turned it upside down and played bass. I ‘ve got a photograph somewhere of Jimi playing my bass. So, I knew him. I don’t know what would have happened had I joined the band, I have no idea. How would it change? I don’t know.

Was there any kind of competition between Alvin Lee and Jimi Hendrix?

I don’t think there was in those days. I think they admired each people’s style of playing or ability and people used to come and see each other. Jimi Hendrix, lots of different musicians would go and see Alvin. Jimmy Page, for example, really liked Alvin’s playing. No, there wasn’t competition. I think what brought the competition was the management, in a way. I’ll say something else about that: The management always wanted to make sure that the band had to headline the show, they got the best lights, the PA, the promotion… To build the band. The only competition we felt was: If we were playing with a band we wanted to get the best reaction. I suppose, in a way, that was a kind of competition, but we did admire the other players a lot. I mean, when I could, I would go and watch the other bands on the show.

Who are your influences on bass?

Who are your influences on bass?

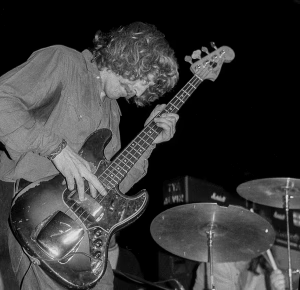

Many. I think when I started out, I liked all the rock ‘n’ roll musicians, Little Richard’s bass player (ed: Olsie Robinson), I liked his style of playing. It was the first time I saw a Fender electric bass on stage. I liked Bill Black, the upright bass player that played with Elvis and then I got into jazz. So, I learned all the rock ‘n’ roll licks and then I started to listen to jazz players like Ray Brown and Scott LaFaro. Duke Ellington had many different bass players but I liked that kind of Duke Ellington’s swing music which you can see in some of the early Ten Years After things where we were doing a simple form of that. So, they are many and now I listen to songs much more. I ‘ve been a songwriter, of course and I listen to the whole song. When I listen to a record, I am not just listening to the bass. I think, in a small way, I concentrated a lot when I was 16 or 17 on learning the bass lines to every pop song, just to practice the thing. I got guitar lessons but I taught myself bass. I ‘m still learning. Now, I ‘d put a record on and I ‘d play along with the record and try to enjoy the music and put my interpretation to it rather than to learn the bass lick that’s on the record, even if it may be brilliant. I may be influenced by that but I just listen to the music as a whole now.

How much has your approach to bass changed over the years?

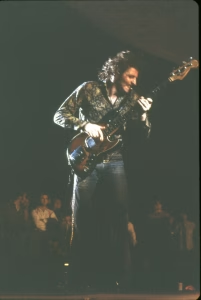

I like to think that I get better, otherwise it would be terrible. So, I’m always trying to do something different. I ‘ve made a lot of mistakes in my music, in my enthusiasm in playing the bass, but I think that’s a good thing, too. I just started jazz, I guess. Now, I think I’m possibly a little more tasteful, but I ‘m playing a different kind of music. With Hundred Seventy Split is a different kind of music: I ‘m playing with a different generation of musicians and the bass has taken a different role in today’s music, even in rock and blues. When I started out the bass set the groove and the drummer played along with it. Now, the drummer sets the groove and everyone else has to fit in. There wasn’t much bass drum if you listen to any jazz record of the ‘60s or any pop music of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Not much bass drum was happening, the bass guitar set the groove and so, I was right upfront playing bass like a lead bass, if you like. Now, I’m a little more subservient to what’s going on. I still stretch out and it’s definitely my style, but I have toned down it just a little bit. But then if I get to play with a drummer that plays in the style of the ‘70s drums, I would just drop slowly back into lead bass (laughs).

Earth, before they change their name to Black Sabbath used to get the intermission spot at Ten Years After concerts. Did you expect that they would become so popular?

Well, it’s luckiness. Hard work and luck, I think. We thought they were a good band and we tried to help them and we recommended them to a few promoters and things like that. I like the guys, Ozzy could be a little crazy at times, but we got along with everyone and yeah, they did well. They are great.

Is it flattering that you have influenced Geezer Butler (Black Sabbath -bass)?

Is it flattering that you have influenced Geezer Butler (Black Sabbath -bass)?

Of course, it is. Very kind of him. Everybody listens to somebody. It’s flattering and very pleasing that you have done something that it doesn’t make me feel that I’m a great musician if I got someone to even start playing or listening to music. I do a little Youtube channel and I get a lot of emails from people who are saying: “I listen to your music and it ‘s really got me interested in playing the bass” and I think that’s great. Because it’s such a wonderful soul-satisfying thing to play a musical instrument, no matter how good you do that. We all need music in our lives, so, yeah, it’s flattering.

Did you like other bass players from your era like Jack Bruce (Cream) and John Entwistle (The Who)?

Yes, I did. Yes. I never tried to play like them but I’m sure our styles cross over. Yeah, very much so.

Did you get to know them?

Yes. We played with Cream a few times, The Who even more. I knew John more than I knew Jack. We were all starting up pretty much at the same time, we were all on this, you know, pretty much along the same festivals. So, you got to see them there and in the earlier days we had all been doing the club circuit in the UK and travelling around. Of course, when you become a stadium act you don’t see them quite as much because they are headlining one and you are headlining another, but up to that point, yeah.

Would you like to share with us any interesting stories from the sessions of UFO’s “Phenomenon” (1974) album that you produced?

Would you like to share with us any interesting stories from the sessions of UFO’s “Phenomenon” (1974) album that you produced?

I think one of the interesting things was: The record company (ed: Chrysalis) signed the band because they thought they would sell some records in Germany. So, the budget they gave me was silly, very low and we got on really well. Michael (ed: Schenker -guitar) didn’t speak much English at the time, but fortunately I spoke German. We got on well and I thought we made a pretty good record in the time we had to make it and the record started to take off, it started to sell and become really popular. It somewhat showed that the record company didn’t wrestle enough and they didn’t get enough to the radio stations and they weren’t enough in the shops and so on, so, it was a bit disappointing for UFO. I think they could have been much bigger had the record company believing them from the first record. I think it was the fourth record when they started to put money into. But I loved it, I enjoyed it. Pete Way (bass) was a particular friend of mine; Pete used to come and stay on a farm with us or in an apartment in London. All nice guys. Pete was crazy of course a bit (laughs), God rest his soul. One thing I could say is that on all the records that I produced with UFO, Pete played my original Woodstock bass. Not a lot of people have done it. He had his Thunderbird bass, but they didn’t record very well; not, in my opinion. So, we always used my Fender bass. So, it’s my Fender bass on the first three records (ed: also 1975’s “Force It” and 1976’s “No Heavy Petting”) I produced for UFO. It lives on.

When you recorded the song “Doctor Doctor” from UFO’s “Phenomenon” (1974) album had you realised that you created a classic song?

Oh no! No, I didn’t. If I could step back and listen to it now, I would say: “Yes, it’s a great song”. “Rock Bottom” I think was another one. In “Rock Bottom” I thought we had something. Someone said we had to edit out for a single. But no. I’m pleased, I ‘m lucky, very lucky. I used to be there (laughs).

By the way, are you aware that “Doctor Doctor” is Steve Harris’ (Iron Maiden -bass) favourite song?

Oh, really?! A funny thing about that. When Iron Maiden were a pub band, I am not sure if they were called Iron Maiden, they had known a man, I think, from a record company at the time. They wanted to sign them and they wanted me to produce the band. So, he and I went to see the band playing and I met the band and I liked the music. I was off for producing but the record label turned them down (laughs), so, I never got to produce them. I was sure it would have been interesting because I knew they were UFO fans, which is why they asked me if I would be interested in producing them. I think we could have had some fun.

Did you find any similarities to guitar playing between Alvin Lee and Michael Schenker (UFO -guitar)?

Did you find any similarities to guitar playing between Alvin Lee and Michael Schenker (UFO -guitar)?

No. Not, really. Michael is a brilliant player but he’s a technician: He works everything out. Everything was worked out. So, if we did a UFO backing track, with just the guitars and he was going to do a solo, he’d go home and he ‘d work the solo out whereas Alvin played off the top of his head. Alvin was an intuitive player, pretty much as I am, I think. I very rarely work anything out, I like to play out in the air. Obviously the technique sometimes dictates the same which makes people recognise your style, whereas Michael was very precise. We ‘d do 8 or 9 solos and I would say about the first solo: “That was great, Michael” and he ‘d say: “For you maybe, but not for me. We do another one” and we ‘d do another 8 or 9 takes and we ‘d listen to the takes and he ‘d say: “I like that bit, I like that bit from that one and I like that bit from that one” and that’s how we worked the solos out.

Did you have fun playing at The Isle of Wight Festival in 1970?

Yes. I always enjoyed playing festivals because I enjoy the energy from the crowd. It was a different festival from Woodstock; it wasn’t raining. I mean, Woodstock, as far as a musician went, it could have been described as a disaster, because there was rain on the stage and there were electricity cables running across the stage with water in between them, so, the risk of being killed by an electric shock was pretty high. I think nowadays they wouldn’t have allowed the festival to go on for health and safety and certainly from the management point of view, they wouldn’t have allowed the bands to play because it was dangerous. But as Alvin said, we were having a conversation: “Well, if one of us dies, we’ll sell a lot of records” (laughs). It was that nonchalance of youth. Now, I would be thinking: “It this worth it? Should we go on and risk death just to play?” I mean, the stage was sliding down the side of the hill. It got people off the stage because the stage was becoming unstable. So, it was pretty hellraising. The Isle of Wight, no problem, the stage worked and you went on and played. The only problem they had at the Isle of Wight was a lot of people who thought all music should be free and they broke down the fences. There was a little bit of trouble, but it didn’t affect us to play there. No, it was fun.

Do you regret not continuing the band with another guitarist when Alvin Lee left in 1975?

In a way, yes. I mean, we had been on the road for such a long time, weeks and weeks at the time over several years, maybe 40 weeks a year or something like that, but it was time for a break. I didn’t feel too bad at the time. I had started a family, so it was good to take some time out. I wasn’t encouraged by the record company to find another guitar player and carry on and that would have made sense from a career point of view to have done that, but we didn’t (laughs). So, I don’t regret it now, no. We reformed several times after that, of course.

Why Ten Years After decided to reunite in 1983?

Why Ten Years After decided to reunite in 1983?

Simple answer: I think Alvin wanted some money. He wanted to earn some money, as far as I can tell. There was no reason. I mean, there were always people asking the band to reform and do some shows for whatever reason and that’s why we went out. Alvin was going through several problems at the time, of a personal nature. They just wanted to earn some money and we got persuaded: “Well, why don’t you do this?” His agent at the time told me that he did some shows somewhere -I don’t know… Bulgaria- and there were 10.000-15.000 people on the show and he said to the agent: “Why can’t you get me shows like this all time?” and the agent said: “Well, if you get Ten Years After back together, we can do it” and I think that was one of the things that he thought: “Well, ok, I’ll give it a go”. So, we did. It all seems so long ago, but we ran for a time and then the same problems cropped up. I think Alvin didn’t want to tour so much and so on. I was quite happy, I produced records but my real love was playing live music, whereas Alvin was quite happy not to go out and tour so much.

When your band The Jaybirds signed with Joe Meek (producer), Ritchie Blackmore’s band, The Outlaws also worked with him as studio musicians. Did you get to know Ritchie Blackmore at that time?

No, not at the time. I don’t know whether Ritchie was in there or had left The Outlaws, but Alvin went for an audition to play guitar for The Outlaws and didn’t get it. So, maybe that was when they were looking for a guitar player, but Ritchie got the job. I don’t know, one or the other. But that’s how I first knew about The Outlaws and Joe Meek. Obviously, with Rainbow, we played with them quite a few times. I found out I was up for the job when Ten Years After stopped touring. Cozy Powell (drums) put my name forward to play bass with Rainbow, but it didn’t feel like the right band for me to be with. Although, at the time, Don Airey (Deep Purple, Ozzy Osbourne -keyboards) was in the band and Ronnie James Dio, who I subsequently I ‘ve worked with, I really liked those guys. I had heard a lot of things about Ritchie and maybe they are unfair, I don’t know, but Cozy said to me: “I think you ‘ll get the gig but Ritchie likes it to play with a plectrum” and I thought: “I don’t want to do that”. So, I didn’t go for the job. I went to see them, they sent me some tickets to go and see them play. So, I didn’t get to play with them. I may have loved it, I don’t know. Maybe Ritchie would have said: “Oh, you don’t have to play with plectrum”, but I think he liked the crystal sound of the plectrum. I had more of an upright tone bass playing and I liked it.

Do you think popular music which was written in the ‘60s and ‘70s is much better than today’s music?

Do you think popular music which was written in the ‘60s and ‘70s is much better than today’s music?

Some is, some isn’t. I think it was more sincere. The thing is: If it comes from the heart and is with feeling and it’s not mechanically manufactured, yes. But there are a lot of artists now that you can call them “organic”; they don’t take four bars of a loop and four bars of another loop and put them together. They go: “Yeah-yeah- yeah-yeah” for four bars and then they put that in there and they manufacture it. “I love you baby- I love you baby- I love you baby” and this is a song. I was a songwriter in Nashville for a number of years, so I’m very critical of a song. What the lyrics are? Do they mean something? Can I relate to them? And there are a lot of pop songs that I cannot relate to. But I’m 80, so what do you expect? (laughs) I don’t drive around my car with something that goes: “WOOVS-WOOVS-WOOVS” (ed: a loud electronic dance beat). I wanna hear the song, I wanna hear the vocals and I found that in a lot of pop music now you can’t hear the vocals. I can hear somebody is singing, but I can’t really hear what they are saying. So, in that respect, I’ve always been a big fan of country music because I can hear the lyrics. I worked in Nashville for 16 years and I worked for a country music publisher writing songs, that’s what I did most of the time, but I ‘ve always liked country music right from Jimmie Rodgers, the country singer and the blues. I think a lot of blues music is generic: “I woke up this morning” or “baby, don’t go” or “I’m feeling down” or “I got no money”, but you can hear the lyrics and you can relate to them.

I did recently an interview with Mel Collins (King Crimson, Roger Waters, Camel), the great saxophone player and he told me that he has trouble relating to Korean boy bands or Japanese-style pop. I mean, in the ‘60s when you were listening to The Beatles singing “Twist and Shout” there was more soul into it than today’s music.

Yes. I would say definitely. But there are exceptions. There is some great music now, some great songs and some great records, but a lot of it just doesn’t interest me. A lot of it. I discover stuff on Spotify or Youtube, of course, I must admit, someone tells me about an artist and I listen to it and I get it. You know, people like Ed Sheeran. I get his kind of music because I can hear what he is saying. I mean, I ‘m not in particular an Ed Sheeran fan, but I like some of his songs and I can understand what is good. Just different artists… In the pop genre, it’s difficult. Taylor Swift, for example, who is right at the top of the pop genre, I like her style because I can understand her songs would be meaningful towards young people, particularly girls, for example. They would like it and she puts on a good show. There are some great people. I still go back to Blackberry Smoke, bands like that, the rockier country music bands. That kind of thing I tend to listen to a lot.

Are you optimistic about the future of blues rock?

Are you optimistic about the future of blues rock?

I think it’s always gonna be there because people are always gonna be able to relate to it and most of the time it’s in the background. It’s not a major forefront of pop music. Pop music is popular music made popular by people that promote it to make money out of it, I guess. You don’t make an awful lot of money out of being an obscure jazz player or a blues musician. One pops through and then ten pop through and that’s the popular music for a time and then it goes back to the basic pop: Find a talent show or a pretty boy or a pretty girl and somebody manufactures a song for them and then someone pays for the video. The marketing, the business has changed quite a lot. That kind of blues will never die. It just comes out of fashion. If I were a blues musician without a pedigree, I could probably scrape a living playing the blues. There is always someone who wants to hear the blues.

Do you think because of the streaming services listening to an album from start to finish is becoming a kind of lost art?

I think, in a way. We were always an album band and an album was always a concept and a number of songs were written at the same time. Often, there was a theme to an album and the band really worked it out a period of time and it went through. With vinyl, we got a great deal of enjoyment out of looking at the album cover and reading where it was recorded, who have written the songs, who the musicians were and all those things. That’s completely lost on streaming and people just promote singles. It’s difficult to say because when I started out in the ‘60s, you didn’t make an album, you made singles and they released singles and they ‘d release two or three singles perhaps and if the first singles were a hit, they ‘d put an EP or an album out. So, it’s going around in a circle, in a way. But I like listening to an album as a concept thing. If there is an album on Spotify, I ‘ll listen to it all the way through. But that’s the way it is, you work with it or you don’t work at all. I accept these things change, but vinyl is coming back now, as you probably know and people are discovering the difference between the sound of vinyl and streaming in headphones over on iPhone. There is a big difference in sound.

How important is improvisation to you?

How important is improvisation to you?

To me, that’s the way I’ve earned my living. So, it’s very important. I worked as a session musician when I was younger, so I used to read music and I always had an idea. Usually a lot of scores were written by pianists, not by bass players for bass players and I thought: “I could do something different there and it’s frustrating”, so I didn’t improvise. Yes, it’s important, it’s the way you express yourself without using words, you express it with the music that you play. If I was just playing the roots of a song or complementing the bottom line of the piano or whatever, then I would enjoy it, but it wouldn’t really be me, no. I’ve played on records as a session player and sometimes people have said, Leslie West (ed: Mountain –guitar, vocals), for example, I did an album with him and Leslie said: “I thought you play over the top”. But I did it with Ten Years After whereas I played there as a session player. I told it back, complementing the vocals, worked with the drummer and left space for the guitar player. He said: “I wanted you to play over the top”. So, that is me, the man that plays over the top (laughs). But I try to do it more tastefully now than perhaps I used to. But that’s it: I’m an improviser. I never prepare anything.

With who musician did you have the best musical interaction on stage?

Well, I think Alvin and I, because we worked together for so long. So, we were two halves of the same thing. I think with my new band now I’ve got quite a bit of empathy or connection, with Joe Gooch and Damon Sawyer, our drummer, because we ‘ve been working now for twelve years. But it ‘s a different kind of music and I’m aware of that, so I tend to play slightly differently. It still sounds like me, but I do it. With Ten Years After, as silly as it sounds, I think I led with the bass. A lot of people say: “You are playing lead bass again”. I feel listening to some of the (ed: Ten Years After) records, the bass kind of leads it, now I tend to drop back a little bit and make someone else lead.

You have toured with everybody. Who was the nicest person you have met in your career?

You have toured with everybody. Who was the nicest person you have met in your career?

Oh golly! I don’t know if I ‘ve got an answer for that. Maybe ZZ Top, I had some fun with them. I thought the nicest person in the business was George Martin, the record producer (ed: The Beatles). I did some work on a record for someone and one of the guys, John Burgess (ed: he produced Manfred Mann’s “Do Wah Diddy Diddy” and John Barry’s “James Bond Theme”), who was a partner with George Martin, they managed Air Studios, they heard my work and they wanted to manage me. John Burgess managed George and he wanted to manage me as well, so that’s how I met George. He was a gentleman and I really liked that. I met him then and I met him at subsequent various things. Yeah, I thought he was a really nice guy.

Did you get to know Rory Gallagher?

No, I didn’t. Listen, there was another funny thing: I went to see Rory Gallagher because the record label wanted me to produce the band, but I don’t know who didn’t want me to produce the band, but I didn’t get the job, anyway. I thought I would like to have worked with them.

Roger Glover (bass) from Deep Purple produced his “Calling Card” (1976) album.

Yes. This was before they put a record out or a major record out, when I went to see them. I felt they were a very exciting band live.

Do you mean with his solo band or with Taste?

With Taste.

They played at the Isle of Wight Festival, too.

Yes, they did, I think, yeah.

I would like to know: What’s your opinion about Chris Squire from Yes as a bass player?

I would like to know: What’s your opinion about Chris Squire from Yes as a bass player?

I think he was pretty good and completely different to the way I play, but he was very talented. I always have a funny thing about Chris because when we were starting out we played with them at The Marquee, it wasn’t Yes, it was a different band (ed: The Syn) and Chris was big-time in the band (laughs) and he made us take all our equipment off the stage and made a set up. You know, it wasn’t very helpful in working together, the two bands. And I remembered that and then Yes toured with us in America as a support band. Our road managers were the same and they said: “What do you want us to do with Yes?” I said: “Well, make them take their equipment off stage” because you normally you accommodate, you are trying to set it up. Not that I ever fell out with them. I knew Rick Wakeman (keyboards), Rick was fine and all the other guys. So, it’s a funny story that I remember (laughs), how Chris said: “You know, you ‘ve got to take all the gear out”.

When Ten Years After started in 1967 as a recording artist, did you get to know Pink Floyd with Syd Barrett who started at the same time?

Yes. Again, we toured universities together. There was the university ball in the UK and Pink Floyd would be on and Ten Years After would be on. So, yes, I knew them. It was after Syd had left. They were fine. The guitar player, David (ed: Gilmour) bought Alvin’s old house.

I didn’t know that.

Yes, it’s a small world.

I’m a huge Steve Marriott (Small Faces, Humble Pie -vocals, guitar) fan. Did you get to know him?

I’m a huge Steve Marriott (Small Faces, Humble Pie -vocals, guitar) fan. Did you get to know him?

Golly, you give me a lot of things to remember! Yes, both in Small Faces and Humble Pie. I toured with them, they supported us on American tours quite a few times. I liked Steve’s stuff. I liked it when he had his Packet of Three as well, a little band called Packet of Three. I thought they were great but the record company didn’t want to sign them. They said: “No, they are a pub band”. I thought they were really good. But yeah, very talented in all three bands.

I ‘ve heard that Ten Years After toured with Led Zeppelin in their early days.

Probably, we played a few festivals with them, yes. I mean, we ran into them on the road a lot because probably we had been staying at the same hotels and things like that. I think we played quite a few festivals with them.

When I saw you playing upright bass, I thought you were like Jack Bruce who started out as a cello player.

Oh yeah! I have always loved upright bass. I had to stop playing it because it wasn’t easy to travel with one but now I have a folding one, that bass folds up. I ‘ve got one in the room here, but I don’t like the stick basses, I like a proper double bass. I love it, yeah.

I am a huge Jack Bruce fan and I don’t think it is a coincidence that you and Jack Bruce are Geezer Butler’s biggest influences. It’s not a coincidence.

Yeah-yeah, probably not. I think both Jack and I liked the same kind of music, I guess, growing up. I never played cello. I started on guitar and then went on to bass guitar and then went on to upright bass because I love the sound of it.

It would be very interesting and extravagant to tour with Cream, with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker (drums). Could you describe to us what was like to tour with Cream?

It would be very interesting and extravagant to tour with Cream, with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker (drums). Could you describe to us what was like to tour with Cream?

I think when Cream split up, Ginger Baker’s manager asked me if I would be interesting in putting a band together with Ginger and I said: “Yeah, let’s get together and have a jam” and then they said: “Well, ok, it would be 3 o’clock in the morning after these particular bars close” and I thought: “It’s not my thing” (laughs). I think it would have been wild. I think Ginger would be the difficult one to work with.

I’ve talked with him. He only answered with “yes” or “no”.

(Laughs) Oh yeah? Yes, I understand. I ‘ve not really spoken to him much. I’ve seen them when they were playing, but I think the only person that I ‘ve spoken to at Cream would have been Eric and maybe Jack a bit, but not Ginger, so I don’t know.

Had you ever met Paul McCartney? You both played at Star-Club in Hamburg.

I said “hello” to him, but I ‘ve never met him. George Harrison (ed: The Beatles -guitar) was a friend of Alvin’s, so I played on one track on one of Alvin’s solo records and George was on. So, I ‘ve said “hello” to them but I didn’t really know them.

Did you get to go to his house, Friar Park?

Did you get to go to his house, Friar Park?

No, I haven’t. I know Alvin used to go a few times. They all lived in the same area, I lived in a different area.

I think Jon Lord (keyboards) from Deep Purple lived there, too.

Yeah. They all lived in the same area, in Berkshire: Jon Lord, Joe Brown, George Harrison, Alvin and several others.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Leo Lyons for his time.

Main photo: Arnie Goodman

Official Hundred Seventy Split website: https://www.hundredseventysplit.com/

Official Hundred Seventy Split Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/Hundred70Split/

Official Leo Lyons website: http://leolyons.org/

Official Leo Lyons Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/LeoLyonsbass