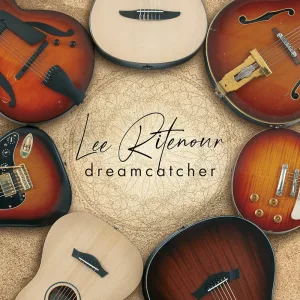

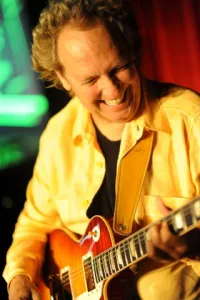

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: March 2024. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary guitarist: Lee Ritenour. He has an acclaimed solo career since 1976, winning a Grammy Award in 1986. As a session musician he has recorded with Pink Floyd, Steely Dan, George Benson, Aretha Franklin, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, Barbra Streisand, BB King and many others. In 2020, he released his latest studio album “Dreamcatcher”. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

How did you come up with the idea to make your first ever solo guitar album, “Dreamcatcher”?

How did you come up with the idea to make your first ever solo guitar album, “Dreamcatcher”?

Well, I think it was in the back of my mind for many years. I’ve always been the band guy, whether it’s on my own records, playing with a drummer, a bass player and a keyboard player, always with great players or in the early days with Fourplay or when I did my sessions with other people. The way I wrote music, the way I produced music, was always more produced with other players, but the one thing I had never done was a solo guitar record. So, it was always in the back of my mind. I wondered if I could do that and how that would be what I would do and then Covid happened and everything stopped. So, I said to myself and to my family: “I guess it’s time for me to make the solo guitar record” (laughs).

How much did the destruction of your house and studio by a fire in 2018 influence the making of “Dreamcatcher” album?

Now I’m sitting in my new studio, which is part of the new house. So, we are back in the new house, it took 5 ½ years. It was a very difficult time losing the house but we had good insurance and we had people helping us, so it was a tremendous amount of work and money and still is, you know. I had bought the original property when I was 27 years old, so, I’m 71 now. The property for me it’s almost like the music and the guitars. It’s part of my blood, so it was important to rebuild.

How emotional was it for you to write “The Lighthouse” as a tribute to the club you watched your early musical heroes such as Wes Montgomery?

The story is fairly well-known now: I grew up in Los Angeles, I was a native in Los Angeles and I grew up only 10-15 minute drive from “The Lighthouse”, in Los Angeles terms that’s very close. So, my dad drove me there to hear many people and of course, Wes Montgomery. I met him when I was very young sitting at The Lighthouse, but later when I met his daughters, after I had done the “Wes Bound” (1993) album, they came in and Wes used to say that this little kid used to come in and sit at the bar (laughs), because in those days little kids could sit at the bar. The bar was the best place to watch the stage because you sat on a stool and you could see the stage very clear. But “The Lighthouse” was important for me because I got to see Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell, Joe Pass and Oscar Peterson. Many amazing great jazz musicians came to The Lighthouse.

The track “DG” is dedicated to your longtime friend and collaborator, Dave Grusin (piano, keyboards). Why did you decide to write a song about him?

The track “DG” is dedicated to your longtime friend and collaborator, Dave Grusin (piano, keyboards). Why did you decide to write a song about him?

Dave is my best friend, he’s my best buddy. We have a new record coming out called “Brazil”, that’s coming out this spring and summer and we went down to Brazil to record that record. He is an incredible musical collaborator. We ‘ve done so many projects together whether is my albums, his albums, his movie soundtracks, on the road with me, big concerts and little clubs. We ‘ve done a lot of hanging together, a lot of dinners, so, we are like brothers. For me, to write this song for DG, for Dave Grusin, it’s very simple melody and I kept reharmonizing the melody with different chords over the melody. So, it starts out pretty simple and then starts to develop and that was the way Dave Grusin works whether he is scoring a film or writing a song for one of our projects. He’s a master at harmony.

I really like “Abbott Kinney” from your “Dreamcatcher” album. What inspired you to write this?

Like I mentioned, when I was working on the record, it was during Covid time; we had already lost the house, so I had set my studio up at another house that we were renting. Again, thanks to the insurance, we were renting this house and I had a room designated for the studio and it was pretty good. But it was right in an area where it was normally a very popular area: Santa Monica, Marina del Rey, Venice and a very popular street called Abbott Kinney and Abott Kinney is always crowded with people. It is just packed and there are good restaurants, little cafés and shops. It’s a very famous area in Venice. So, it is usually crowded but during Covid, especially when everything was shut down, one day I drove my bike on Abbott Kinney and it was completely empty. Nobody was out and they were telling people to stay inside. It was a little too much what they were suggesting: Nobody could travel, nobody could go anywhere, the restaurants were closed, it was a disaster. But I got on the bike and I was driving around and I drove down Abbott Kinney and Abbott Kinney was completely empty. I had never seen it like that, even at 4:00 in the morning. But then, all of a sudden, I heard this guitar jamming away with a lot of distortion and some -I don’t know if it was a kid, a guy or a girl or a pro or an amateur- it sounded pretty good but whatever they were doing, they were having fun and they turned it up loud, just jamming away with this rock guitar distortion. It was vibrating down the whole street and I just laughed to myself and I said: “Ok, that’s a sign. I have to do a song like that”

Do you have trouble coming up with titles for instrumental pieces?

Sometimes when I do have a title in mind and it has a reason for that title, sometimes it helps compose the song. So, “Abbott Kinney” was a perfect example. Of course, I had to call the song “Abbott Kinney”, but it was for that reason.

Were you surprised when you won the Grammy Award for Best Arrangement on an Instrumental for “Early AM Attitude” in 1986?

Were you surprised when you won the Grammy Award for Best Arrangement on an Instrumental for “Early AM Attitude” in 1986?

That was a long time ago (laughs). It was for “Harlequin” (1985), the album that Dave Grusin and I did, the Brazilian-themed record. Again, that’s just part of Dave’s and my history. I think I ‘ve had 16 Grammy nominations and that one win and then Dave -I don’t know- he has 10 wins and a bunch of nominations. It’s nice to be recognized by your peers, but again, as everybody says, for the most part, they are just valuing the artists and they are recognizing that they are doing good work. So, we appreciate that. Dave Grusin is a perfect example, his wife always got mad at him -the rumour has it- because Dave had so many awards: Academy Awards, Grammys and all sorts of awards and they are stuffed in the bathroom and in shelves and not very organised. Some people have everything lined up perfectly on the wall and Dave was much more casual about it. So, the awards don’t help you make better music. It doesn’t work that way but it’s nice to be recognised.

Did you have fun making the “Larry & Lee” album with Larry Carlton in 1995?

Yes, as a matter of fact, I did. I ended up producing a lot of the record and Larry kind of came in and out. Of course, he was always playing great and he contributed some songs and when we did the tracking he had his drummer that he requested and sometimes we would have Abraham Laboriel (bass), who we both loved or we would have Greg Mathieson (piano, keyboards) or somebody else that I used. We ‘ve known each other a lifetime and we were always kind of competitors, but the GRP Records, Larry Rosen at the time, Dave Grusin’s partner at GRP Records, really suggested we do the record. That was 1995. Larry later told me he was less involved in the record because he still was getting through the physical thing with the painkiller medicine for when he got shot, even though that it was years earlier (ed: in 1988). He wasn’t living in LA then. He was obviously very involved in the record, it was half his record, but he left a lot of the production elements to me. What I was going to say about that record is that now in the streaming, you hear Larry Carlton streaming or you hear Lee Ritenour streaming and quite often the “Larry & Lee” album would pop up on the streaming and it sounds actually pretty good (laughs).

How much has your approach to guitar changed over the years?

I started out as a studio musician a long-long-long time ago and I was always a very good rhythm player, I consider myself a good lead player, but when I made my first album called “First Course” on Epic in 1976 -that’s a long time ago- the guys in the band, I remember Tom Scott on saxophone, Harvey Mason on drums and a few other players, most of them were all friends, but they were giving me a hard time. They ‘d say: “Oh, you are in the driver’s seat now, you are the leader”. So, that was an interesting transition because as a studio musician your job is to back everybody else up and make them sound good and when you are the leader on the record, your job is to make yourself sound good. Of course, you still make the other players in the band sound good, but they are supposed to make you sound good. I always worried about: Did I have enough of my personality on that first record? And it turned out I did, it was already there by the time I made the first record and that was 1976, so then I was 24 years old.

Did you enjoy recording “Lay It Down” with John Scofield (Miles Davis -guitar) on your “6 String Theory” (2010) album?

“Lay It Down” with Scofield? Absolutely! I always loved John, still do. He is timeless on the guitar. I think when he started out playing and doing his thing, which is also many-many years ago and the way he does it now, he had a style that could blend with the jazz guys, the funk guys, the rock guys and the blues guys and it was always John Scofield. So, when I wrote “Lay It Down”, I wrote it for the two of us and we got together and we went over the tune and he just played incredible on this song and I am big fan of his.

What was the concept behind The 6 String Theory Competition featuring many great musicians as judges (Steve Lukather, Andy Summers, Joe Bonamassa, Pat Martino and others)?

What was the concept behind The 6 String Theory Competition featuring many great musicians as judges (Steve Lukather, Andy Summers, Joe Bonamassa, Pat Martino and others)?

Well, the concept for The 6 String Theory Foundation came out of the record, because on the record my idea was to feature the guitar playing jazz, rock, blues, country, classical and folk in accompaniment guitar, all the different major brands of guitar playing I wanted on one record and I thought that I could produce that record and I did it along with producer John Burk, who was at the time at Concord Records, now he is at Candid Records, a new label, which my new Brazilian album is coming out on. So, John and I thought that it would be so cool to have all these amazing guitar players on one record, whether it was George Benson or Steve Lukather, all these guys. Then, at the same time we were having all those incredible players, I thought: “Wouldn’t it be great to have a competition that the winner of the competition gets to play on the record as well?” So, we did that and a young classical guitarist (ed: Shon Doublil) won it at the time. We had to stop that Foundation around the Covid time, because it was too crazy to keep it going at that time, but it’s very much on my mind to start it again. I am planning another 6 String project coming up very shortly.

With many guests?

Yeah, I want it to come out in 2025 and I want to have 25 guitar players (laughs).

Any names?

Well, I am gonna hold the names because we haven’t made the invitations yet. There are some new, young incredible guitar players out there and of course the established ones. So, I have many ideas. I have to keep it a secret for now.

Could you please share with us the great story about your participation in George Benson’s “Give Me the Night” (1980) song?

(Laughs) George is again somebody I grew up with before I met him, listening to him and I was always blown away how amazing he was on his early records, but also guesting on those Creed Taylor-CTI productions that he would play on. He had the sound, theses chops and the time and rhythm. So, we got to play together quite a bit. Because of my studio background, I always loving play rhythm guitar and playing also the accompaniment parts. I’ve played on a number of George Benson’s records as the second guitar and George always used to joke that whenever Lee was on his records, he would have a hit (laughs). So, Quincy Jones started producing George Benson’s “Give Me the Night” and I had already worked a lot with Quincy and loved Quincy. Quincy called me and said: “You know, we are doing George Benson. You are gonna work on the record and I want you to freshen up his sound with maybe a few subtle pedals or effects, just be in charge of bringing his sound up to date”. Of course, I didn’t have to do much. George’s sound is George’s sound, it’s already great and the most important thing: You don’t want to mess with that too much (laughs).

But anyway, we did several sessions and Quincy as usual had all the greatest players on the record. So, we were just about done with the record and Quincy and Bruce Swedien were mixing the record and George had already flown back to his home in Hawaii, so he wasn’t in LA and the record was being done in Los Angeles. They were doing it at the studio that it’s no longer there in Burbank called Kendun Recorders and I had a house very close to that studio and one night I got a late call. I think I was sleeping and I got this call from Quincy and he goes (ed: He mimics his voice) : “Ritenour, you ‘ve got to get down there!” “Down where?” I said. “To the studio. We screw it up and we erased part of George’s solo on ‘Give Me the Night’ and you ‘ve got to fix it”. I said: “Where is George?” and he said: “George is back in Hawaii. The record is due tomorrow. We ‘ve gotta finish it. We made a mistake”. I think the second engineer accidentally hit “record” and just went to record on the track which was George’s solo and that was at the end of the solo when the second engineer clipped a little part of it. That was a big mistake, unfortunately. So, it’s like 11 or 12 o’ clock at night or something and I go down to the studio and they play it for me and they say: “Lee, George’s equipment is here. His guitar is here”. I said: “I can’t play George’s guitar” because George’s strings are very thick. So, they say: “We ‘ve got to get this sound, you ‘ve got to sound like George”.

But anyway, we did several sessions and Quincy as usual had all the greatest players on the record. So, we were just about done with the record and Quincy and Bruce Swedien were mixing the record and George had already flown back to his home in Hawaii, so he wasn’t in LA and the record was being done in Los Angeles. They were doing it at the studio that it’s no longer there in Burbank called Kendun Recorders and I had a house very close to that studio and one night I got a late call. I think I was sleeping and I got this call from Quincy and he goes (ed: He mimics his voice) : “Ritenour, you ‘ve got to get down there!” “Down where?” I said. “To the studio. We screw it up and we erased part of George’s solo on ‘Give Me the Night’ and you ‘ve got to fix it”. I said: “Where is George?” and he said: “George is back in Hawaii. The record is due tomorrow. We ‘ve gotta finish it. We made a mistake”. I think the second engineer accidentally hit “record” and just went to record on the track which was George’s solo and that was at the end of the solo when the second engineer clipped a little part of it. That was a big mistake, unfortunately. So, it’s like 11 or 12 o’ clock at night or something and I go down to the studio and they play it for me and they say: “Lee, George’s equipment is here. His guitar is here”. I said: “I can’t play George’s guitar” because George’s strings are very thick. So, they say: “We ‘ve got to get this sound, you ‘ve got to sound like George”.

So, back in those days they had a little cassette of George’s solo that they have given to George and said: “Is it ok? Are you signing off on this?” So, the solo was there and the second engineer had only erased a few bars but it was enough and destroyed the very end of the solo, I remember. So, we set up George’s equipment and I got his guitar out, played it for a while and I got used to it and then I listened to the cassette over and over and over and we kept patching and comparing the sound and finally we fixed the solo. Then, Quincy said to me: “Lee, you can never tell George this happened. Never tell him. You promise?” “Ok. I promise”. So, the record came out, it was a huge hit and then, like 10 years later -now “Give Me the Night” has become one of his biggest hits- and George and I were walking in the airport with our guitars and we were going to the same festival or something and I said: “George, I ‘ve got to tell you a story. I wasn’t supposed to tell you this story, but 10 years later, Ι think it’s ok to tell you now”. So, I told George the story about “Give Me the Night”, fixing his solo and the whole thing and he and I just had a huge laugh. He thought that it was the greatest story (laughs).

How did it happen to play in the songs “One of My Turns” and “Comfortably Numb” from Pink Floyd’s “The Wall” (1979) album?

The producer was Bob Ezrin (ed: Alice Cooper) , a great guy, and I had worked with him on a couple of other projects that he had produced. I liked working with him and he had called me in advance to come down and play some acoustic guitar because he loved my acoustic guitar playing and he wanted us (ed: Lee and David Gilmour) to play together and have me join on acoustic guitar. So, I get down to the studio and I bring this big trunk of guitars, like 21 guitars around this huge trunk. I thought to myself: “The band is gonna be blown away with it” when I rolled in with all my pedalboard. But then I was the one blown away because this studio, it was called Producers Workshop and it wasn’t too big a studio, but lined up in guitar stands were… I don’t know how many guitars this guy had, but he had all the best guitars in the world and they were line up perfectly, in good shape: Electrics, acoustics, 12-strings, classicals, Strats, Les Pauls, whatever. The guy had everything. So, that was fun. When I walked in into the studio they were working on the solo for “Another Brick in the Wall”.

He (ed: Bob Ezrin) said: “What do you think of the solo?” I think the solo is very short, it’s like 8 bars long or something, it’s not too long. He said: “We just can’t figure out how to end the solo. We are not happy with the ending. Would you mind just playing a few things? We are not gonna use anything that you do, but we need some other ideas, some inspiration”. I said: “Yes, sure”. He said: “Let me hear the solo and the sound”. So, I set up my equipment and I tried to get a little close to his sound and they played me the track many times and then I punched in a few ideas, for not too long, about 30 minutes. We did -I don’t know, I don’t really remember- maybe 10 takes and they said: “Ok. That’s great. Let’s move on now. That’s a bunch of good ideas. Thank you, Lee, for that little help”. So, we moved on to the acoustic tune that we played together. I can’t remember which song we started with (laughs). Then, we started to work on the reason that I was there, but a year later when the record came out -they took forever to do their records- I was really interested to hear the ending of that solo and it was definitely not me, but I felt like maybe there was a little inspiration from what I did.

He (ed: Bob Ezrin) said: “What do you think of the solo?” I think the solo is very short, it’s like 8 bars long or something, it’s not too long. He said: “We just can’t figure out how to end the solo. We are not happy with the ending. Would you mind just playing a few things? We are not gonna use anything that you do, but we need some other ideas, some inspiration”. I said: “Yes, sure”. He said: “Let me hear the solo and the sound”. So, I set up my equipment and I tried to get a little close to his sound and they played me the track many times and then I punched in a few ideas, for not too long, about 30 minutes. We did -I don’t know, I don’t really remember- maybe 10 takes and they said: “Ok. That’s great. Let’s move on now. That’s a bunch of good ideas. Thank you, Lee, for that little help”. So, we moved on to the acoustic tune that we played together. I can’t remember which song we started with (laughs). Then, we started to work on the reason that I was there, but a year later when the record came out -they took forever to do their records- I was really interested to hear the ending of that solo and it was definitely not me, but I felt like maybe there was a little inspiration from what I did.

I ‘ve read that you played in “Run Like Hell” from “The Wall”, too. Is it true?

Well, I’ve read that, too (laughs). I think I did, but I don’t think I got credit on that one. But I can hear my guitar part on that, as well. They were a little nervous in those days because they were a band. A very-very famous band and they were supposed to be doing everything by themselves, but they had a few guests, they had some background singers, they had a few other people lending their sound to the album and the album had such a massive, big sound. Sometimes, they needed extra people. So, I think I’m on that track too, but you know, it’s a long time ago (laughs).

Was it an interesting experience for you to play on Dizzy Gillespie’s “Free Ride” (1977) album (with Lalo Schifrin -keyboards)?

The funny thing about those sessions, I think Lalo Schifrin was the producer, and it was up at the Fantasy Studios and the Fantasy Studios were in Berkeley. They were always doing these jazz albums and some very-very famous jazz players were making their records, but when they would call me or Harvey Mason (ed: Fourplay, The Headhunters -drums) or a couple of the other LA guys, mostly Harvey and me, we would go up and record but they were always hoping that they would record something more commercial, more contemporary with a newer sound. Sometimes Patrice Rushen (piano, vocals) was on those sessions and Ed Greene or Harvey Mason on drums. Sometimes there would be four or five different players come up from LA and lend the sound to these records. So, the same way I worked on a Dizzy Gillespie record and on a Sonny Rollins record and these guys were gods to me, absolute heroes, but we were asked to do the more commercial tracks. What Harvey and I wanted to do was play some jazz with these guys, but they wanted us to add more of that LA contemporary sound in the ‘70s then. So, what I’m trying to say is that that wasn’t always the best tracks or the best records that those guys made, but it was an honour to work with these, it was an honour to work with Sonny and later I got to meet and hang with Dizzy, he was always holding court at the Montreux Jazz Festival or these places, so it was an honour to be on those records.

Do you have any memories from the “Deacon Blues” sessions with Steely Dan (from 1977’s “Aja” album)?

I didn’t work as much on Steely Dan records as some other guys like Dean Parks and Larry Carlton, but they always called me a lot to record on their records but I was always already booked, so they would call: “Hey Lee, what are you doing tonight?” or “What are you doing tomorrow?” and I said: “Oh God, I’m so sorry, I wish I could come and record with you but I am already booked”, because in those days we were doing three sessions a day, sometimes seven days a week. So, when I did get to play on “Deacon Blues” on the “Aja” album, they would have you overdub and overdub and overdub and they would keep all the parts and then later they would orchestrate and go through it. You wouldn’t know if you are on the record until the record came out (laughs). So, I remember one session with David Foster (keyboards), Michael Omartian (keyboards), Jay Graydon (guitar), Dean Parks and me, we were all on some big session together and “Aja” had just come out and everybody was asking: “Did you make the cut? Are you on the record?” (laughs) So funny. But they made incredible records and to this day, the songs are great, the lyrics are great, the production is great. I’m a huge fan.

How much impact did the guitar lessons you took from Joe Pass and Barney Kessel have on you?

How much impact did the guitar lessons you took from Joe Pass and Barney Kessel have on you?

The real impact was from a guy called Duke Miller who taught me everything I know about the guitar, but Joe Pass was one of my all time favourite guitar players. So, my dad called him up one day, I think I was about 16, and he got Joe Pass’ number out of the phone book. On those days we had those big phone books and his Italian name (ed: Passalacqua) was on the phone book and my dad got hold of him and he said: “I have a very talented son, can he get a guitar lesson from you?” My dad wasn’t shy. So, we drove to the San Fernando Valley, which was far away from our house and Joe had a little set up behind his garage. He had a little music room, a separate room after garage. So, I walked in there and Joe was always an Italian tough personality. He said: “So, play me something kid” and I ‘m very nervous. Very nervous. I’m trying to think exactly how old I was. I might have been 14, 15 or 16, somewhere around there. I played him some stuff and then Joe says: “Well, what do you want to learn from me?” and I said: “I want to learn how to play jazz like you, Mr. Pass”. He said: “Hm, ok. Well, when I play this minor 7th chord and I go to the 5th chord and then I go to the I chord, sometimes I do this scale and then I’ll do this alteration and then I’ll do this arpeggio and this scale”. He is playing all the stuff and I’m listening and I said: “Excuse me, Mr. Pass, but it never sounds to me like when I am listening to your playing and your records, that it sounds like you are playing scales” and he said: “Oh no, that’s just the way I explain it. That’s not the way I think about it. I ‘ll tell you what, I’ll play some stuff, if you like something, stop me and I’ll show to you” (laughs). So, that was the lesson and the truth of the matter is that Joe grew up playing by ear. He was influenced by all these great jazz musicians and he developed this incredible ear and he could copy Charlie Parker or Dizzy Gillespie or Bill Evans, whoever he was listening to and he had this great feel on the guitar and of course he had his own style. So, I never learned to play like Joe Pass but I certainly loved working with him.

You are the only great jazz guitarist who hasn’t performed in Greece yet. Is it possible to play in Greece soon?

Man, I’m overdue. I hope one day before I get too old (laughs).

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Lee Ritenour for his time. I should also thank Mr. Gary Lee for his valuable help.

Buy “Dreamcatcher” album here: https://lnk.to/LeeRitenour

Official Lee Ritenour website: https://leeritenour.com/

Official Lee Ritenour Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/LeeRitenourMusic/