HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: May 2015. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary producer: Joe Boyd. He is best known as the producer of the first Pink Floyd single, “Arnold Layne” and Nick Drake’s first two studio albums, “Five Leaves Left” and “Bryter Layter”. He has also produced: Fairport Convention, The Incredible String Band, Eric Clapton, Soft Machine, Nico, R.E.M, 10,000 Maniacs and many more. In 1966, he opened the historic UFO Club, the center of the psychedelic scene in London. In addition, as the Director of Music Services at Warner Bros, he collaborated with Stanley Kubrick on the soundtrack release of “A Clockwork Orange”. His autobiography “White Bicycles – Making Music in the 1960s” was published by Serpent’s Tail, in 2006. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

Are you satisfied with the feedback you got so far for your autobiography “White Bicycles – Making Music in the 1960s”?

Are you satisfied with the feedback you got so far for your autobiography “White Bicycles – Making Music in the 1960s”?

Yes! I mean, it got very good reviews and it’s so very well that I have a new career talking to audiences, reading from the book and sometimes performing with Robyn Hitchcock, who sings the songs that I read about in the book. It has been great. It has been now nine years since the book was released and everybody seems to like it. So yes, I ‘m very happy.

How difficult was the writing process of your autobiography “White Bicycles”?

Not very difficult. I’ve been telling all these stories for many years. In fact, one of the reasons I wrote the book was because I had been asked to talk about those events all these years on the radio and on television. I started to get interviewed more and more often and I began to realize when I was telling all these stories, that I was getting quite gloomy with telling a story that I realized that I was trying to remember the last time I told the story, rather than remembering the moment itself back in the ‘60s. I said: “Let’s I write it down soon. I’ll have too many layers of storytelling between me and the event”. I said: “Let’s put it down on paper before I lost the direct connection to that time in my memory”. Because I ‘ve been asked to tell these stories a lot, the time flowed quite easily, once I decided on the structure and the approach.

Are you currently involved in any projects?

I’m writing a very different sort of book right now, which is much more difficult. I’m writing a book about the phenomenon we call world music. The relationship between the bourgeoisie of the western world and the music of the developing world. I’m doing a lot of research and interviewing people not to have just my own story, but there is a lot of history, a lot of things happened a long time ago. So, it’s not just the last 30 years. This phenomenon goes back hundreds of years that the West being fascinated by exotic music.

What do you remember the most of the UFO Club days?

Well, I remember of course Pink Floyd on stage in those great nights. The first 3 or 4 months of the club were the best for sure, because at that time, there were a lot of friends, people knew each other. There was a feeling that a special club, group or people who were in, are becoming secrets about music, about art, about life, about so many things. Then, by March or April 1967, psychedelic music and the underground scene became much more popular and it started getting crowds of people who had never heard that kind of music or had been in that kind of place, so the atmosphere changed a lot. But there was still an adventure every week. It was quite spontaneous, quite different every week. It was a lot of fun. There were very interesting personalities and very creative people involved. It was a great memory.

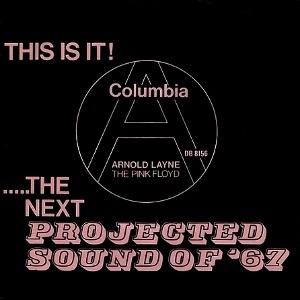

When you produced the first Pink Floyd single, “Arnold Layne” (1967), did you expect that they would become an extremely successful band?

When you produced the first Pink Floyd single, “Arnold Layne” (1967), did you expect that they would become an extremely successful band?

I did! I believed so much in Syd Barrett, his songs and the group. I thought they were great. What surprised me, it was that they became hugely successful without Syd. I thought they would have so many difficulties without the great person that I had met. I expected Pink Floyd to decline and possibly disappear but they became even more famous without Syd, than they were with Syd. So, that was a big surprise.

Was Syd Barrett an easy going person to work with?

He was great to work with. He was very nice and smart but he was quiet. He wasn’t very loud or outspoken. Roger Waters did most of the talking but there was always a check with Syd. They looked over at Syd and made sure that he approved what they were doing or saying. I only worked with them in the studio for two days making that single and then one more day doing “Interstellar Overdrive”. So, I don’t have a long history working with them in the studio, but I knew them quite well from the events I did for them so often and all the preparations for the studio and it has been always a real pleasure to work with them.

How emotional was the last gig Pink Floyd played at the UFO Club?

Not very emotional at all, because it was part of a kind of big mistake that I made. We had friends to do a UFO festival out in the country, in a big tent on the first bank holiday weekend in September and the promoter, the guy who owned the tent kept delaying signing the contracts. Then, we discovered that he was trying to book the groups separately, without UFO being involved. I got very angry and we booked all these groups that we planned for the festival in the country, for a festival at The Roundhouse. I booked The Roundhouse for Friday and Saturday in that weekend, I think the last weekend in August in 1967. It was really a mistake because I did it just to stop this guy from cheating me. But in fact, we had all these groups: Pink Floyd, The Move, Arthur Brown, all these people booked for The Roundhouse, for a big festival in the weekend that everybody left town and went out to the country. There was beautiful weather, people didn’t want to be inside, so we lost money. We didn’t know at the time that it would be the last gig. It was only afterwards that we realized that in a way the magic has gone from UFO and we better stop before we lose money. So, nobody thought that it was the last gig and I think Syd was in a little better shape than he was the time before, in the beginning of August. I don’t really remember if Dave Gilmour was playing behind him. I really have very few memories of that last gig.

Do you wish you produced “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” (1967)?

Sure! Yes.

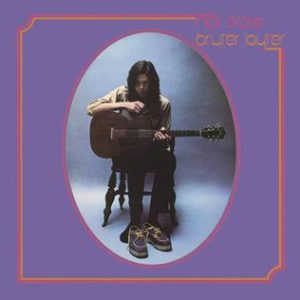

What was it like being in the studio with Nick Drake?

What was it like being in the studio with Nick Drake?

He was great. He was so professional, so perfect. He was one of the best studio musicians I have worked with. He never did a bad take. He was always perfect and the songs were so wonderful to work on. Because they were so good, so original and when you added other musicians to play with Nick, it kind of bloomed and they blossomed and they became really exciting. When you listen to a live recording by Fairport Convention, Pink Floyd and The Incredible String Band, you may have heard it. How to play songs that way, live. But with Nick, you are hearing things for the first time. You are hearing songs and frames for the first time. You hear Richard Thompson (ed: Fairport Convention –guitar), Danny Thompson (ed: Pentangle -double bass) and Nick playing the songs. Every session with Nick was very rewarding, very exciting, very interesting.

Why it took so long for people to discover the music of Nick Drake?

I think there is a combination of reasons: He didn’t play live or not very much. He was very shy and he wasn’t very good live. And he didn’t have an audience. Many artists, successful artists usually build up an audience through live appearances before even releasing a record or they tour in support of the record. They do a lot of things to spread their music out to the public. Nick didn’t do that. We were only relying on the record itself. Now, it’s so customary to hear male singers sing very quietly that primary kind of jazzy folk hybrid. Something that it isn’t quite folk music, it isn’t quite bossa nova, it isn’t quite pop music. It’s in the middle. Now, it’s everywhere. You can hear it from many different artists every week. Being this way or perform functioning their music this way. But in 1969, it was very unusual. No-one was knowing what he was doing and I think most people were unfamiliar with his music, and they thought it didn’t fit in any category. Considering that Nick wouldn’t go out there promoting himself, eventually he didn’t really have a lot of radio shows, he did one session with John Peel for the BBC Radio One in 1969, but there was a very little opportunity to get radio airplay for Nick, and all things ended up in a very difficult situation to get Nick at the top. So, it took a long time for word of mouth to get across to people.

Why Fairport Convention’s “Liege & Lief” album is so different from their previous one, “Unhalfbringing” (both released in 1969)?

After the recordings of “Unhalfbringing” the drummer (ed: Martin Lamble) was killed and they decided that couldn’t just carry on like a normal group and replace the drummer and play the same songs. They decided never to play the same songs without their original drummer. They needed a completely new repertoire. They were very influenced by the “Music From Big Pink” by The Band (1968) and they decided to be inspired by that record, which was so much about American roots music and they looked inside Britain’s roots music to find a new repertoire, a new style, a new way of making their music. So, that’s the reason.

You recorded the legendary Led Zeppelin/ Fairport Convention jam at Troubadour Club in LA (Sept 4, 1970). Can you tell us about that night? Will we ever listen to that recording?

You recorded the legendary Led Zeppelin/ Fairport Convention jam at Troubadour Club in LA (Sept 4, 1970). Can you tell us about that night? Will we ever listen to that recording?

It sounds better in theory than it sounds when you listen to it (laughs). And it wasn’t really all of Led Zepellin, it was just Jimmy Page and Robert Plant. I think John Bonham was also there. John Bonham was a friend of Dave Pegg (ed: Fairport Convention –bass). They were both from Birmingham. Fairport were playing at the Troubadour, the same night Led Zeppelin were playing at the LA Forum. So, when Zeppelin’s gig was over, they came by the Troubadour. The Troubadour was a very nice club, its owner liked music and he would let people stay late, even though you had to stop serving alcohol. At a certain point, he would just close the doors and anyone inside could stay. I was there making a live record with Fairport and when Jimmy Page and Robert Plant got up on stage and joined Fairport, we just kept recording. I can’t remember what they played. They did one that was like a English dance and that was quite funny hearing Jimmy Page try to keep up with Richard Thompson on that.

The other two things I remember about it were: The Troubadour had a very small stage and usually our problem was that the amps were right behind the vocal microphone. So, sometimes it was difficult because you had a lot of sounds from the guitar and the drum kit coming into the vocal microphone and sometimes being quite loud against the vocalist. Sometimes you would have trouble hearing the vocalist in front of the sounds of the drums amplifier. But when Robert Plant was singing a song, we were having the opposite problem. His voice was so loud it went down the microphone upon the end. In those days, you didn’t have direct connections to amps to mix them and you had to put a microphone in front of the amplifier. And Plant was so loud with his own mic, that also he was almost as loud as the sound of guitar on the guitar amplifier. And on the drums microphones you were hearing as much Robert Plant’s vocals, as you were hearing the drums. So, that was the problem.

The last thing I remember about that mix, was that one of the regulations of the club was that you have to take any alcoholic drink off the table by a certain time. Peter Grant, the manager of Led Zeppelin, who was a notorious thug, he was sitting in the front of the stage, in a very quite song, Dave Swarbrick was singing I think the “Banks of the Sweet Primroses”. There is a lot of quiet in the song and suddenly you hear this noise and this blasting, rattling and you hear the waitress saying: “Excuse me, I have to take the wine off the table” and Peter Grant yelling: “Get your fuckin’ hands off my bottle!! Get fuck out of here, you cunt!!” And we have that on tape, which is quite entertaining.

Why the Soft Machine single, “She’s Gone”/ “I Should’ve Known”, recorded in 1967, remained unreleased for many years?

I don’t know. I think they asked me to make one session with Soft Machine, we recorded two songs. I remember seeing a single with the title on it, but people say it was never released. I don’t really remember what happened but eventually it came out on a compilation.

Are there people in music business like John Peel nowadays?

Are there people in music business like John Peel nowadays?

Yes! I think Cerys Matthews is like John Peel. She has a show on BBC Radio 6 Music every Sunday and she’s great. She plays a lot of different kinds of music and she has a great character. But I don’t really listen to radio much, so I ‘m sure now that there are people on the radio like Peel, but I don’t know who they are, because I don’t really listen to the radio.

Did you meet John Lennon at The 14 Hour Technicolor Dream concert (29 April 1967) where Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, Tomorrow and others performed?

No. I know that he was there, but I didn’t meet him there.

What exactly was your role on the soundtrack release of Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange”?

I was working in California for Warner Bros. films and my title was Director of Music Services. It really meant that I was in charge of music soundtracks for films. But being in charge didn’t really mean having any power. I was pretty much there as I discovered when I took the job, that they really wanted the film director get to do whatever he likes and my job was get him anything he needed. So, Kubrick called me and he said: “I need this recording from Deutsche Grammophon or the Beethoven Symphony get it for me”. So, I got it for him. He would tell me what he wanted and I was just doing his liking. It wasn’t a very creative job and Stanley Kubrick was a brilliant director and his use of music in the films and particularly in “A Clockwork Orange” is fantastic, but I can’t claim any creative input. It was all Stanley Kubrick and I was just there to make the deals and do what he told me.

Do you remember the night Jimi Hendrix jammed with Tomorrow at the UFO Club?

No. I remember him coming down but I don’t really remember him jamming. Maybe, but I can really say what I remember.

Were you flattered when Paul McCartney, Pete Townshend and Eric Clapton visited the UFO Club to watch Syd Barrett playing with Pink Floyd?

I wouldn’t say flattered. It seemed logical that they would come down. I think we were a little bit proud that we had a club that people wanted to come to and thought that something important happening there. I remember those people coming down but I wouldn’t say flattered, no.

Was there any kind of competition among producers in the ‘60s?

Was there any kind of competition among producers in the ‘60s?

Well, sure. The producers very often signed groups, so there was sometimes competition who would sign a group. I think most producers had a good respect and friendship for each other. I was very good friends with Paul Rothchild (ed: The Doors, Janis Joplin) and Denny Cordell (ed: The Moody Blues, Joe Cocker). So, there were few well-known producers that I knew back then and I learned a lot from Paul Rothchild particularly. He taught me a lot. There was a comraderie more crafties have. You know, somebody does horse riding and rides horses for a living and you meet other people who do the same and you have an affinity with them. And I think there is the same thing for record producers.

Why you didn’t produce Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” (1975) album?

Well, I don’t know whether I would have been asked to produce it. All it happened was that I knew John Hammond who was A&R man for Columbia Records and I had never heard Bruce Springsteen. I heard of him. I heard that he had two records that had come out on Columbia that had not done very well. I was in New York and I had a phone call from John Hammond and asked me if I would come to see Bruce Springsteen playing the following week in New York and he thought that I might be a good person to produce his next record. I was already scheduled to fly to London before that date. I think Hammond might had sent me the two LP’s that he had already released and I went and listened to the two LP’s and I thought for myself: “Well, it’s not really my cup of tea”. So, I didn’t change my ticket. I just went to London. I don’t know if I would finally produce him. It depended on how I liked the show, how Bruce Springsteen and I, got along. They might have been plenty other candidates to produce. So, there was no commitment. It wasn’t like that I turned down the chance to produce him. It was a very preliminary moment, so I don’t know what would have happened. I know that Jon Landau (ed: Springsteen’s manager and record producer) did a fantastic job. I think it’s lucky for Bruce Springsteen that I didn’t produce the record, because Jon Landau made a much more commercial record that I might have made. I think, I might have made a very commercial record but Landau.. It’s one of the great stories when a producer meets an artist and they are coming up with something, way better than anyone expected. They had a big success that no-one thought coming. I’m prepared to say that I think I would have made as good record as “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn”. Maybe, a better record. But I won’t say that about “Born to Run”, because I didn’t have the same feeling about the music of Bruce Springsteen that I have about Syd Barrett.

Do you think the collapse of the major recording labels is a kind of justice for their corporate greed all these years?

Do you think the collapse of the major recording labels is a kind of justice for their corporate greed all these years?

Well, I ‘m not sure that justice is ever done in the world of corporate greed, which is all- pervasive in the world today, particularly as you know very well where you are calling from. I don’t know. It’s a very complicated question. Because the music industry is involving technology, popular taste, education, population growth, economic conditions, immigration… There are so many factors brought together to make up what music is successful and what music is not successful. The one thing that I would say now is that everything that might have been done before, had been in the way that you could expect from a classical situation. Independent, small companies, original thinkers, outsiders, rebels can make it much better in the music industry, than they do in almost any other industry. I think it’s more difficult for corporations to conform the music business, than any other business. You have automobiles or cable television, all these things require so much capital to get started that it’s impossible for a small company to really compete a big company. In music, it is one of the few areas where a small company, can compete a big company and can have a big, big success and surprise everyone. But I think in the last few years, we are now looking at the worst situation we have ever looked at for independents, for audiences, for outsiders, because of the horrible deal which has been done by Spotify, for example. It had sold big shares to Sony BMG and I think to Warner Music. So, the record companies are now partners with the retail outlet in a way that is completely destructive for the interests of artists and songwriters. If I had the time and the money, I would file a huge lawsuit, I think.

Are you happy with the comeback of the vinyl records?

Well, in a way. I think it’s nice, but I find it shocking and depressing that 99% of the newly pressed vinyl is pressed from a digital master and therefore what’s the point? It’s like a CD on a vinyl.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr Joe Boyd for his time and to Claudia for her valuable help.

Official Joe Boyd website: http://www.joeboyd.co.uk

Official Joe Boyd Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/joeboydproducer