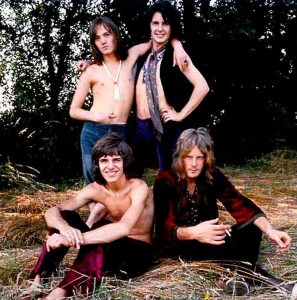

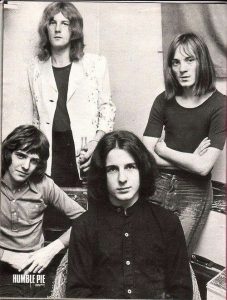

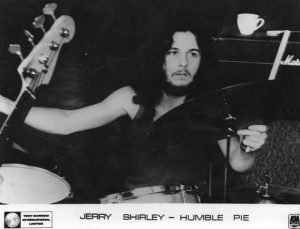

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: December 2023. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary musician and a true gentleman: Jerry Shirley. He is best known as the drummer and founding member of Humble Hie, appearing on all their albums. He also formed Fastway (with Motorhead guitarist “Fast” Eddie Clarke and UFO bassist Pete Way) and has made recordings with Syd Barrett (“The Madcap Laughs” and “Barrett” –both released in 1970), The Who bassist John Entwistle (“Smash Your Head Against the Wall” -1971), George Harrison (the seminal “All Things Must Pass” -1971) and BB King (“B.B King In London” also in 1971). The latest release by Humble Pie is the magnificent “The A&M CD Box Set 1970-1975”. Read below the very important things he told us:

You didn’t perform during the Humble Pie Legacy US tour last autumn. What’s the concept behind “Jerry Shirley Presents Humble Pie Legacy”?

You didn’t perform during the Humble Pie Legacy US tour last autumn. What’s the concept behind “Jerry Shirley Presents Humble Pie Legacy”?

Well, we decided to reform the band about 5 years ago, before Covid hit. I couldn’t go on the road myself because of medical reasons: I just had my hips replaced and I couldn’t perform. We had just released the box set of all the albums that were on A&M on vinyl (ed: “The A&M Vinyl Box Set 1970-1975”) and we were following it up with a box set of the same albums on CD. So, we then decided to put together a new version of Humble Pie, but we were trying to figure out how to bill it, because we wanted to be honest and let them know that there were no original members actually performing, although it was sanctioned and organized by the original member, myself, who owns the name. You see, I own the rights to use the name. So, we came up with: “Jerry Shirley Presents Humble Pie” and it was originally: “Performing the musical legacy of Humble Pie”, but that was too long. So, we just shortened it to “Humble Pie Legacy”. That was fine, the tour went fantastically. The band consists of a guitar player who is the musical director, because he was in Humble Pie with me back in 2000 with the original bass player, Greg Ridley, before he sadly passed away. Dave Colwell, the guitar player, took the position of being the musical director on my behalf. I was organizing what I wanted and he was finding the right musicians and putting the band together.

We went out and did a small tour in 2018 and then we were about to continue it when Covid hit. We couldn’t go on the road for a couple of years and during that period of time, we reogranised the line up: We got a new lead singer, Jim Stapley, who is wonderful and the bass player is Ivan Bodley, he previously performed with people that were Stax Records artists, Sam & Dave and people like that and then Bobby Marks, who is a drummer from New York, who plays a lot like me. So, we had a line up in place and then I was introduced to Steve Karas (ed: Toto manager) and between us we worked with the record company to release the CD box set, while we put together the tour. Now, the only problem we had was we decided to call it “Humble Pie Legacy”, so that no one could accuse us of trying to tell them that it was the original band. They couldn’t be because two of the original band members are dead, they are no longer with us and I couldn’t perform anymore. So, a lot of bands today are still using the name, but they are not the original members. They are sanctioned by whoever owns the name. But there is another side to this and that is: There is a lot of what they call “tribute bands” out there that have nothing to do with the original line up, they are not connected in any way. They just copy the original: They try to look like the original, they play the songs identically, while we are not doing that.

This is a new Humble Pie and the mistake we did make was when we used the “Legacy” tag, we found out once we got out there that a lot of the tribute bands are using that very tag. There is Genesis Legacy out there, there is Emerson, Lake & Palmer Legacy, that kind of thing. So we are now in the process of rename it. We probably gonna just bill it as: “Jerry Shirley’s New Humble Pie” and then in the press we’ll put: “Performing the musical legacy of Humble Pie”. That’s a long winding way of explaining it, so I ‘m sorry that I took me so long (laughs), but that about covers what happened. The tour went fantastically; every place they played the crowds got bigger and bigger, night after night and the reception, they were going crazy. So, obviously we got the right line up and hopefully now that my health is improving, I will be able to go out with the band and play a few songs here and there. I can’t do a whole set, but I can at least get out and perform. Maybe we can get some guest artists to come up and perform with us: Chad Smith, the drummer with the Red Hot Chili Peppers is a friend of mine and he’s prepared to get out and do a couple of songs with us. Clem Clempson, the guitar player that took Peter Frampton’s place, he said that as the band progresses, he will get out to play here and there. It’s all coming together very nicely.

Are you satisfied with “The A&M CD Box Set 1970-1975”?

Are you satisfied with “The A&M CD Box Set 1970-1975”?

We went to great lengths to remaster it, so that we use modern technology to make it sound as if it’s just been recorded. You can do that today, you can take old copies of tapes, that maybe the original tape has been lost and has deteriorated. You can take the digital footprint of it and remaster it to make it sound brand new. So, that was my goal: To make all those great albums we made to sound as if they just had been made in a brand new studio yesterday, if you know what I mean. It is packaged beautifully and it has a booklet with it that tells the whole story of Humble Pie and I’ve very proud of it. It is selling very well, it is very well-received as was the vinyl version that came out back in 2017. So, it is all rebuilding nicely and we hope to be out on the road next year (ed: 2024), in the second half of the year, from the early summer right through the fall. We are in the process of putting those tours together now, but it’s a great band. Have you seen any of the footage of the new band?

Yes. The singer is great.

I mean, we spent a lot of time and money filming that and recording the live performance of a few songs and it shows what a great band is. We are not trying to just be a copy of the original. We try to do a new version of those great old songs and that basically is the difference between this and a tribute band that has nothing to do with us, has no business connections or anything… You know, they are loving it. The other side of this is that the young audience that are primarily into streaming the music; they get the music from streaming as opposed to having a vinyl record or CD. Our streaming numbers: In 2015 we had barely 5.000 people who knew of Humble Pie on Spotify and all these various streaming outlets. We now have 3,5 million and an average of 350.000 people streaming every month. By other artists who are big in streaming that’s not huge, but for us to go from 5.000 to 3.500.000 it means that the younger people are being made aware of that wonderful music that I’m very proud to be part of when we made it 54 years ago. So, it’s all going very nicely, Theo. It really is.

Was there a lot of pressure when you formed Humble Pie to become more successful than Small Faces?

No, because we were just trying to make a brand new band as good as it could be and the Small Faces was so fantastic, but we accepted the fact that they had made such a huge mark on the latter part of the ‘60s, in England especially. When we formed, we were being called a supergroup and hadn’t even started yet. So, that’s we called it Humble Pie to sort of say: “Wait a minute, you know, we want to go out and prove ourselves from ground up”. We didn’t feel we were competing with Steve’s (ed: Marriott –vocals, guitars) past with the Small Faces or Peter’s (ed: Frampton –guitar) past with The Herd or even with Greg Ridley, the bass player, who was with a band that was well-known called Spooky Tooth. I’m the only member who came from an unknown band (ed: The Apostolic Intervention), but I was only 16 at the time. So, we had a lot of work to do to prove ourselves and it took about 18 months to two years of hard work, touring mostly in America, but also in Europe and England and eventually it paid off when we recorded the live album (ed: “Performance Rockin’ the Fillmore” -1971) and then we went on from there.

Are you proud that “Performance Rockin’ the Fillmore” (1971) is considered one of the best live albums of all time?

Well, it’s great honour to have people to describe it as such. When you do something like that -and I was only 19 years old when we recorded “Rockin’ the Fillmore”- 20, 30, 40 years later when you look back and you see that it is being compared with, let’s say The Allman Brothers live at the Fillmore (ed: “At Fillmore East” -1971) and a couple of others, that is one of the best live albums ever recorded, it is just huge pride. It’s like looking at someone else’s life, because I’m now 71 and when I started with the band I was 16-17. It’s a great privilege and a great honour to have been part of that band back then, because they could have had any drummer they wanted and they chose me and I‘m very grateful they did. Part of my job now is to keep the band’s name alive with a great new line up. Lots of bands are doing that, they have to because some members have passed away or they are no longer able to go on the road. With a few exceptions like the Stones and The Who, you can’t really go on the road and rock really hard when you are in your 70s and 80s (laughs).

So, there is nothing wrong with getting younger people to come in and perform your music for you. I compare it to the classic composers. Beethoven wrote that music years ago. After he died, it is still being performed to these days in orchestras all over the world. More recently, in World War 2, the biggest band in the world was the Glenn Miller Orchestra, and in 1944 he went down in a place crash on his way to France to do a charity performance for the troops. When the plane crashed, he died and his family had to decide what to do. So, they went ahead and performed with his orchestra without him and to this day, The Glenn Miller Orchestra is still performing his music all over the world. So, it just proves that whilst the people in the band didn’t survive, the music does and it has to be looked after by someone like myself who was in the original band or the families of the band. Lynyrd Skynyrd have no longer alive original members, but the families of the band keep a version of Lynyrd Skynyrd on the road and they do wonderful business. That’s what we try to achieve: To keep Humble Pie’s music alive and so far this new line up is doing a wonderful job. If you ‘ve seen those videos we made, you know how good it is.

So, there is nothing wrong with getting younger people to come in and perform your music for you. I compare it to the classic composers. Beethoven wrote that music years ago. After he died, it is still being performed to these days in orchestras all over the world. More recently, in World War 2, the biggest band in the world was the Glenn Miller Orchestra, and in 1944 he went down in a place crash on his way to France to do a charity performance for the troops. When the plane crashed, he died and his family had to decide what to do. So, they went ahead and performed with his orchestra without him and to this day, The Glenn Miller Orchestra is still performing his music all over the world. So, it just proves that whilst the people in the band didn’t survive, the music does and it has to be looked after by someone like myself who was in the original band or the families of the band. Lynyrd Skynyrd have no longer alive original members, but the families of the band keep a version of Lynyrd Skynyrd on the road and they do wonderful business. That’s what we try to achieve: To keep Humble Pie’s music alive and so far this new line up is doing a wonderful job. If you ‘ve seen those videos we made, you know how good it is.

Do you have any memories from the Shea Stadium concert opening for Grand Funk Railroad on 9 July 1971?

That was probably the highlight of the band’s career while Peter was in the band. After he left, there were other highlights of course, when Clem Clempson was in the band. I found out just recently, a few months ago, that between 1965 and 1971, there were only three British drummers that performed at Shea Studium. The first one was in the band that opened up for The Beatles, the British drummer called Tony Newman in a band called Sounds Incorporated. He was the first. The second one of course was Ringo playing on the same bill on that night with The Beatles. Then, six years later, in 1971 we opened up for Grand Funk. So, that meant that I was the third British drummer to ever play at Shea Stadium. Again, this is the privilege and the humility of doing something like that. When you find that out, 45-50 years later and I can look back at it and I remember looking up and seeing that they were all moving! You know how stadiums have tiers of spectators, one layer of people and then another set of people and the whole stadium was moving from the people jumping up and down! It was just a remarkable sight. My biggest memory was: It started to rain, really heavily. Back in those days, you weren’t protected against being on stage with electricity and water, through rain. Today, with everything being wireless, it is not dangerous. Back then, it was very dangerous, you had to stop playing. What Steve Marriott did, was he went to the front of the stage and he said to the audience: “I know it’s pouring with rain, we don’t give a f…, we are gonna rock ‘n’ roll you all night long!” and the place went absolutely nuts. They just loved it. We all were wet out and got soaked together and then thankfully no one got electrocuted (laughs)! But it was an incredible night and Grand Funk were very gracious to us: They gave us all the room in the world; they didn’t try to restrict the amount of time we had to play. They were very generous to us and they became very good friends of ours, too. A great bunch of guys.

I love your drumming in “Live With Me” from “Humble Pie” (1970) album. Could you tell us about your approach to this?

Well, it started out as a free form jam but it didn’t have any lyrics. It was just instrumental. The way I came in, I knew it had to start with a certain type of roll, which is usually referred to as a “press roll” and once we started doing it when we were recording that track and we all came in together, it just exploded. It was just a great feeling. We got all the way to the end of the take. I think by then we had found and got together some lyrics, and while we were playing the backing track, the guys were singing just what you call a rough vocal to be done later and they turned out to be so good, we just kept them. I think, if I’m not wrong, it was the first take. It was just a piece of magic that happened out of nowhere, starting as a jam and it ended up as a complete song.

Please tell us everything we should know about the great song “30 Days in the Hole” (from “Smokin’” album -1972).

Please tell us everything we should know about the great song “30 Days in the Hole” (from “Smokin’” album -1972).

There was a sign at the time about the Rolling Stones that they were living in “elegant debauchery” (laughs) and Steve wrote a song that was a kind of tribute about how on Earth we got to play on the road whilst not having much fun and doing things that we wouldn’t recommend anybody doing today. It was making references to different types of pot you smoke or different types of drinks that you drink, but he said: “If you do all that, what you get is 30 days in the hole” meaning you go to jail for 30 days. Where he got that line from was our manager at the time was telling us a story about getting into a road rage fight with another driver and they ended up going in front of a judge. The other driver who had this fight with, got himself all bandaged up as if our manager had beaten him up badly. He hadn’t. Because this guy was pretending to be beaten up, the judge fell for it and he said: “Are you going to admit to what you did here, because if you don’t I’m gonna sentence you to 30 days in a hole?”, in other words 30 days in jail. So, he told us this story and Steve remembered the line. It was a kind of funny story, but he remembered him saying: “If you don’t admit it, you are gonna go and get 30 days in a hole” and that’s what the songwriters do: They hear a line or a phrase someone said and they remember it and use it in a song that might have nothing to do with the guy that was talking about, but they just like the sounds of these lines. So, that’s where “30 Days in the Hole” came from.

Mick Abrahams (original Jethro Tull guitarist) auditioned for you before Clem Clempson join the band. Why didn’t he get the job?

Mick Abrahams came to audition. We knew him, he was a friend of ours. While we were warming up, so he could hear what we are doing, we were playing as a 3-piece at the rehearsal room we used and he had his guitar with him, but after he heard us playing as a 3-piece he said: “I can’t add anything to that. It sounds great just like it is” and he put his guitar back in the case. He said: “You guys, you don’t need me. You sound fine, just like that”. So, he left as friend still. It was a big compliment of him to say that, but we knew that we did in fact need a guitar player and luckily for us Clem Clempson had heard through the grapevine that Peter had left the band and we were looking for a guitar player and so he got in touch with us and he came down and rehearsed with us and the next day he was the new guitar player. It was that simple.

Could you tell us the great story about Clem Clempson’s call to Steve Marriot?

Like I said, he heard that we needed a guitar player and he managed to get hold of Steve’s number from somebody and Steve pretended to be Steve’s brother. Steve doesn’t even have a brother (laughs), he has a sister, but the reason he did that was because he had never heard Clem’s playing. He said: “Well, I’m his brother, but when he gets back, I’ll have him call you”. In the meantime, he went to the nearest record store and bought Clem playing on “Colosseum Live” (1971) album that had a slow blues on it (ed: “Encore… Stormy Monday Blues”) that Clem was playing beautifully on. So, as soon as he heard that, he called Clem back and then and he said: “This is Steve. I understand you called looking for me earlier, why don’t you come down and have a jam and see if it works” and that’s what happened. He was putting him on, so he had enough time to go and a find an album that Clem played on and he could hear it. He immediately knew he was the right guy for the job.

Did you have trouble in Humble Pie deciding what songs should cover for your albums?

Usually, each one of us would come up with a suggestion. It was either as group we liked a particular song, we would re-arrange it and do it our own way or one of us would suggest a song and then we would go about the business of re-arranging it. We did a lot of covers but every time we did them, we tried to make them our own, so they were nothing like the original. I think we succeeded in that, in a sense. For instance, our version of “I Don’t Need No Doctor” is nothing like the original Ray Charles version, but we made it our own and I’m very proud. That was done at a soundcheck when we were on the road with Grand Funk at Madison Square Garden. We were doing a soundcheck before the show and Peter Frampton came up with the chord changes and I started playing along with him. Greg joined in and then Steve jumped up on stage and started singing “I Don’t Need Not Doctor” on top of what we had been doing. So, they would come about in lots of different ways. If we liked the song, we‘d do it, it didn’t matter if it was written by someone else or written by us. If we liked it, we did it.

What was the greatest skill Steve Marriott had?

What was the greatest skill Steve Marriott had?

Obviously his voice, but a lot of people don’t realise how good a keyboard player he was. He played brilliant piano and Hammond organ. He was a fantastic blues guitar player, a lot better than people realise. He was a very good drummer, too. But obviously his main talent was that incredible voice of his, like no other. No one sang like him and no one has done since. All the top singers: Robert Plant, Paul Rodgers, Mick Jagger, David Bowie, may he rest in peace, all say Steve was the finest white blues singer to ever come out of England. So, it was a very big privilege and an honour to be his drummer for all those years.

How emotional was it for you to play at the Steve Marriott Tribute Concert at the London Astoria in 2001 along with Peter Frampton, Greg Ridley and Clem Clempson?

Obviously, if you ask, it was the highlight of the night and I think a lot of the audience felt there were two highlights: Our performance and then at the end of the night when Paul Weller, Noel Gallagher (ed: Oasis guitarist), Kenney Jones (ed: Small Faces, Faces, The Who -drums) and Ian McLagan (ed: Small Faces, Faces –keyboards) got together to do some of the Small Faces biggest hits and I was invited up to play drums alongside Kenney on “All or Nothing” and “Tin Soldier”. For me personally, those were the two highlights: The Humble Pie set where the audience went nuts; we played great together and that was the only time that we had ever played together: Clem and Peter had never played together before and then at the end of the night getting up and playing drums next to Kenney Jones, who was my boyhood hero. It was one of the greatest moments that I ever had. It was wonderful.

Did you have a good time in Pittsburgh opening for Alice Cooper where the fans were jumping up on stage and almost demolished the stage?

That’s correct! You’ve done your homework, haven’t you? (laughs) The nicest thing about that night after we were being on stage and the audience jumped up on the ramp that had been built for Alice to go out from the front of the stage. It was 10 meters out -however long it was- but it was only built to hold Alice. When Steve went out, the audience jumped up on this ramp with him and it almost collapsed. Thank God, it didn’t. But anyway, we went down a storm. It was one of the biggest receptions I remember I was getting from an audience and Alice was so kind. After our show and before he went on, he came to our dressing room and he leant against the doorway and he looked at us all: “How the fuck do you expect me to follow that?!” (laughs), which is a very-very kind of him. He did, by the way, went out and did a brilliant job and he followed what we had done; he rose to the occasion. He didn’t shoo away from it. Forgive me for swearing here, but that’s exactly what he said. Again, the stadium, you could see it moving. It was literally going up and down. The top row of the stadium, you know how the stadiums are built, the seats were miles away from the pitch or the stage and you could see it moving up and down. It was just remarkable. A brilliant night. It really was.

Ian McLagan told me that Robert Plant was a huge Steve Marriott fan. Is it true?

First of all, he used to follow the Small Faces around when they were at their height; this was before Led Zeppelin. What happened was, in the beginning apparently Jimmy Page wanted Steve Marriott as a singer, but Steve didn’t want to leave Small Faces. He recommended another guy who was a friend of ours, called Terry Reid. Terry Reid was busy with his own career, so he recommended Robert Plant. That’s how Robert got the job with Led Zeppelin, apparently. All this time, Robert was following the Small Faces, as a fan. Later in life, when Humble Pie were doing a farewell tour in 1975, we were playing in a place called The Warehouse in New Orleans, which was a brilliant venue. It was a hot and sweaty night club that held about 2.000 people packed to the rafters. We didn’t know that they were gonna do it, but our management arranged for Led Zeppelin to come and watch our farewell show. I was on stage playing on the second song, I looked to my left and there’s John Bonham standing there watching me -almost fell of my drum stool- and I turned to my right and there’s Robert Plant and Jimmy Page sitting on the side of the stage watching us perform. So, the highlight of the farewell tour for me it was the fact that three out the four members of Led Zeppelin chose to watch our show. They were performing about 60 miles away. So, they went on stage early, so they could finish in time to get to our late show, because we were doing two shows that night. Then, after that when I was playing in a band with Steve in England, it was called The Packet of Three and we would play small clubs in and around Birmingham, where Robert Plant is from -he is from the Midlands, anyway- and there is a particular club called JB’s and every time we played there, Robert would show up to watch Steve with this 3-piece band I was in with him. He has said: “I only wanted to be Steve Marriott”. That’s the famous quote from Robert Plant.

How did you get to play on Syd Barrett’s studio albums “The Madcap Laughs” and “Barrett” (both released in 1970)?

How did you get to play on Syd Barrett’s studio albums “The Madcap Laughs” and “Barrett” (both released in 1970)?

Syd was a friend of mine and a drummer called Willie Wilson. Willie and myself shared a flat and Dave Gilmour was producing the records and he needed somebody to make sure that Syd got to Abbey Road on time, because he didn’t drive. So, Willie and I would drive him there and it was actually Willie Wilson, who was the drummer for The Sutherland Brothers & Quiver, who did most of the drumming on “The Madcap Laughs”. I only did a couple of tracks. On the “Barrett” album, I did most of the tracks and it was all because David Gilmour lived just around the corner from us and I was privileged to be asked to do it by David. I didn’t realise at the time that 55 years later or whatever is, there would still be as much interest about Syd Barrett and those two albums as there is. They just released the documentary about him and I have a small appearance in. I don’t know if you have heard about it. The documentary is called: “Have You Got It Yet?” and it is gonna be released worldwide soon, I think. Anyway, the drumming on those two records was shared by Willie Wilson and myself. Again, often Willie doesn’t get the credit that he should do, because he did most of “The Madcap Laughs” and I did the “Barrett” record. My two favourite tracks that I played on are “Gigolo Aunt” and “Baby Lemonade”.

I know that Syd was showing up at your doorstep at very weird hours.

Syd would show up and say: “Alright, should we go out clubbing? Should we go to The Speakeasy?”, which is the place that all the rock ‘n’ roll people would go late at night, except it was 8 o’clock in the morning. So, we would say: “Come on in, Syd” and Syd would sit with us and drink tea and smoke pot until it was 11, 12 o’ clock at night and then we would go to The Speakeasy, the club that everybody went to. It was his idea to go there, but once he got there, he frowned. He clammed up. It was like he shut down, he wouldn’t talk to anyone. Being in a public eye, being in a night club like that, really had a bad effect of him, because this was after he had this bad experience with LSD. Yes, he used to do that. He used to show up 8 o’ clock in the morning thinking it was 11 o’clock at night.

My favourite Syd song is “No Man’s Land” (from “The Madcap Laughs”) and you played drums on that song. Do you have any memories from its sessions?

That song was on “Madcap Laughs” and is credited as my playing on this? To be honest, I have to listen to it to remember it. It’s such a long time ago. The ones that I told you about already are the ones that I remember. My favourite track on the “Barrett” record it’s not me or Willie, it’s actually Dave Gilmour playing drums and that’s on a track called “Dominoes”, which is a beautiful song. Syd couldn’t get the guitar part right, so Dave came up with the idea of playing the tape to him backwards. So, when you turn it back and play it normally, the guitar part is backwards. He did this in the first take: He listened to it backwards and he got it perfect (laughs). He made it. Anyway, “Dominoes” that’s to me the best song and the best recording in both of those records.

You played a historic now concert at Olympia Exhibition Hall with Syd and David Gilmour. Did you ask Syd afterwards why he put down his guitar at the fourth song, “Octopus”?

You played a historic now concert at Olympia Exhibition Hall with Syd and David Gilmour. Did you ask Syd afterwards why he put down his guitar at the fourth song, “Octopus”?

Dave and I, were dumbfounded. We were playing along and Syd was a little shaky but it got to the fourth song and he just stopped. Like you say, he put his guitar down and walked out. As far as I remember, he walked out and then kept going. He just left the building. As I say, “Elvis has left the building”. He just left. I can’t remember Dave and I even asking him why he did. It was a last minute thing, anyway. His record company and his manager had decided to have him play a live show to promote his record, but he hadn’t played live in years and Dave and I tried to help him. It was a very rough and ready thing: It wasn’t well-rehearsed and just frowned during the fourth number and he just quit and we never knew why. Again, he had trouble facing audiences, I think.

How did you decide to form Fastway with “Fast” Eddie Clarke (Motorhead -guitar)?

“Fast” Eddie and Pete Way, the bass player from UFO had decided to form a band and they wanted me. I didn’t know either of them, but a mutual friend put them in touch with me and they came down to see me at my house and we talked about it. I didn’t know either of them. I lived in America and I had just moved back to England while Motorhead and UFO were big in England but they weren’t well-known in America, so I didn’t really know anything about them. I just said to them: “Yeah, I am interested” and I didn’t have a job at the time. “As long as you guys you are taking this seriously, let’s give it a go”. I think they were a bit shocked that I wasn’t more excited about it, because I didn’t know them. As soon as we started playing together, it was great. We had a record deal in no time at all, we wrote all the songs equally and we found a singer, Dave King, from a small advert that we put in a British music press. He was the one and only singer that we tried and as soon as he started singing, we knew he was the right guy. And now, it was a great band! It’s a shame that it didn’t perpetuate beyond two albums. By the time we finished the second album and the second year of touring, we were a really powerful live band. But they wanted to use machines instead of us live musicians. So, they got rid of us and they made a record with machine drumming and machine bass playing and they didn’t sell. The ones that had me and Charlie McCracken (ed: a member of Taste, Rory Gallagher’s first successful band), the bass player on, sold really well. The machine-made records didn’t work. I spoke to Eddie Clarke, may he rest in peace, years later about it and he said it was the biggest mistake he ever made. The management talked him into getting rid of the live musicians for this record and use machines and it didn’t work enough. But I loved the two albums that we made. I was very proud of “Say What You Will” (ed: from the debut album “Fastway” -1983) because it came from something that I started. I wrote the music part, Eddie re-arrange it a bit and Dave King put the vocal on top. So, it was literally a proper 3-way effort.

Could you describe to us your first meeting with Jimi Hendrix at Olympic Studios?

I was 14 at the time, maybe I was just turning 15 and I was doing sessions for Steve Marriott when he wanted to work and the Small Faces had finished working. He stayed in the studio and he was using me. Back then, I was so shy that I would play with my head down. I wouldn’t look up, I would look at the snare drum. I was hiding behind the drums. He did this to me twice: The first time I look up and I see Steve Marriott with Jimi Hendrix next to him, looking at me while I am doing the drum check, so the engineer could hear what the drums sounded like. I just very quietly put the drum sticks down and started to walk away from the kit and Jimi put his arm around me and he said: “That’s really cool, man. That’s really cool. Well done!” Of course, for Jimi Hendrix to tell you that what you just played was cool, you know, meaning really good, was helping me a lot. He could see I was young and shy, but he was very kind, he was a real gentleman, Jimi. He really was. A lovely man. And then, a few days later, Steve did exactly the same thing and in this time it was with Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts. And I look up and see Charlie looking at me and Charlie did a similar thing. Again, I was 14-15 years old and very shy and Charlie said: “Ppfff!!! That’s enough for me that I wanna choke my wrists off!” (laughs) In other words, he was trying to say that what I was doing was better than what he does, which of course it wasn’t. I mean, he was the finest drummer that ever came out of England. Between him and Ringo, keep it simple and keep in the beat and not getting all the flashy stuff happening. He was a master at it. He was the master of what not to play.

A funny question now: In the film “Almost Famous” (2000) during a card game a tour manager traded the groupie Penny Lane to Humble Pie for $50 and a case of beer. Is this a true story?

A funny question now: In the film “Almost Famous” (2000) during a card game a tour manager traded the groupie Penny Lane to Humble Pie for $50 and a case of beer. Is this a true story?

That didn’t happen. That’s just Cameron Crowe (ed: director) taking bits of stories that he had heard or Peter (ed: Frampton –he was a consultant on the film) might have told him a few things here and there and then he wrote script to fit the whole movie, but that actual occurrence did not occur. That did not happen. We didn’t trade a groupie for a case of beer… And it wouldn’t have been Heineken because we hated Heineken (laughs).

Did you enjoy recording John Entwistle’s “Smash Your Head Against the Wall” (1971) album?

We did the whole album, I think, in five days. We did two tracks a day. It was in total 10 or 11 tracks because there were a couple of bonus tracks that came out later. It was a very emotional time for me because my mother was in the hospital dying of cancer and we were all praying she would survive, you know, that she could go into remission. But actually while I was finishing the album, we had a weekend off and I went to visit her and she died on the Saturday and John Entwistle was really sweet and lovely about it. Because he was financing the whole thing, I think he paid himself and the guitar player £300 pounds each and he paid me £150. When I went off on the weekend and mum died, he heard about it and I had to go back on the following Monday to pick up my money and to listen to the rough mixes and he gave me my check and I opened it up and it was for 300. In other words, he doubled the amount I was supposed to get and I looked at him and he only said: “I thought it might help, given the circumstances”. I thought it was a very sweet thing for him to do.

Keith Moon played Latin percussion on that John Entwistle’s album. Did you get to meet him during those sessions?

Oh, yeah. He helped me because we were hiring a drum kit, because my kit was in America. We were in between tours and we were hiring a drum kit from the big drum shop in London. The only thing I asked them for specifically was a certain type of a bass drum pedal and when it got there the kit, it didn’t have the right bass drum pedal. This drum shop, called Drum City went notorious for treating young, up-and-coming drummers badly and only treating the big stars nicely. Keith had been through this with them, because when The Who was starting out and he was smashing his drums every night, he was having to go to them and get drums and they were not treating him well. But then, The Who became big and they treated him well. So, he comes to see me at the opening of the sessions and I am really down because I wasn’t sent what they supposed to and he asked me what was wrong and I told him. So, he called up Drum City and gave them a huge chiding, told them off big time and he gave them a huge bollocking and then within 10 minutes, the bass drum pedal that I wanted was there, thanks to Keith telling them off. He was lovely about it. It was great.

Who are your influences as a drummer?

Who are your influences as a drummer?

So many. Let me see: We start with Kenney Jones and Bobby Henrit. Bobby Henrit played with Argent and The Roulettes (ed: and The Kinks). Then, Brian Bennett who played with The Shadows. Keith Moon, of course. Then, we go further into the American guys, who were the real influences. They were Sonny Payne, who played with Count Basie; Gene Krupa, of course Buddy Rich, although I could never play like him. It was for seeing him and Gene Krupa doing a drum battle for the first time that made me want to be a drummer. Al Jackson from Booker T. and the MG’s. The drummer from Little Feat, Richie Hayward. Who else? Bernard Purdie. “Pretty” Bernie, one of my biggest influences. He is an African-American drummer who played with Aretha Franklin, Steely Dan, one of the best session players ever. He invented what became known as funk; funky drumming. He was the first guy to play a certain way that ended up being called funky drumming or funk. Oh, there are so many. Levon Helm from The Band. The list is endless.

Is it flattering that you influenced Chad Smith (Red Hot Chili Peppers)?

He is a few years younger than me, but he was old enough to know about Humble Pie when we were at our height and his brother, Brad Smith, who was a big Humble Pie fan, would encourage him to sit behind their drum kit in their garage and keep playing along with our version of “I Don’t Need No Doctor” until he got it perfect. I was just talking to him yesterday about it and he marks Humble Pie and my drumming as one of his big influences, which is an incredible compliment. I think he’s my favourite drummer now of the modern drummers, but he has been around for a long time now. If I would pick one of the drummers that are at the top of their game now, Chad is my favourite. So, it was both ways and he’s a really-really nice man. He owns my drum kit, the most famous drum kit that I’m photographed playing with Humble Pie at their height. It was found in a bar in Portland, Oregon 40 years after I sold it to the drummer for Buster Pointdexter. He started out as David Johansen (ed: the singer of New York Dolls) and he took on this new identity as Buster Pointdexter. His drummer bought it from me and then it went on a long journey, through God know where and it ended up as the house kit in bar in Portland, Oregon. A lovely guy called Don Bennett found it and renovated it and Chad now owns it.

Do you think popular music which was written in the ‘60s and ‘70s is much better than today’s music?

I think it has more feel, it has more humanity to it. There is too much machinery involved in making records now. You know, the best records are the ones that are made by human beings sitting in a room with live microphones, playing together and making magic. I think that’s why that music from those times has a better flavour to it because it’s got a human element involved in it. But that’s just my opinion.

There’s a nice photo of you with BB King. What’s the story behind this photo?

There’s a nice photo of you with BB King. What’s the story behind this photo?

I played on his album years before, in London. He made a record “B.B. King in London” (1971) and I was one of several drummers on the album and then fast forward 20+ years, he was playing in Cleveland, Ohio and I was living there raising money for a disabled children’s day camp where disabled children could go and have fun for a day and just do whatever they want. It was called Camp Cheerful. We took this guitar which was donated by a friend of mine called Brady Bulger and BB King was one the first people to sign it for me. Then, Bob Dylan signed it, Paul McCartney, George Harrison… You name it, they signed it. Sadly, it was kept by the people that organise the day camp and it was held in a bank’s safe deposit place because the bob fell out of the market of that stuff in the mid ‘90s. So, I had to hang on to it for a while and a lot of the people that signed it have now passed away: It was David Bowie, George Harrison. There is plenty of them. Eddie Van Halen signed it. All kinds of people. Steve Winwood signed it. It would be worth a fortune at auction today, but no one knows what happened to it. I believe they auctioned it off at a black type of auction and then it sort of disappeared. If someone could find it and auction it today, it would be literally worth millions with all the people that signed it.

Ginger Baker in his documentary (“Beware of Mr. Baker” – 2012) said: “John Bonham had technique but he couldn’t swing a sack of shit”. Do you agree with this?

He is wrong. Ginger was very opinionated about what he believed. He said that about John Bonham but later he said: “John Bonham is the best one”. Of all the drummers out there John Bonham is the one that he thinks as the best. So, he was contradicting himself. He is wrong. I think John Bonham swung better than Ginger Baker. Because to swing is a way of playing drums. You know, if you don’t swing, it doesn’t mean a thing. Anyway, I thought Ginger got that wrong (laughs).

Do you have any regrets in your life?

Jeez. That’s a good question. I’ve been sober now for 27 years and a lot of time before that was wasted drinking too much, but I’m glad that I stopped doing it and I’m also glad that I stopped smoking. So, really I don’t have too many regrets. I’m very lucky, I’m very grateful. I just had some surgery on my heart, but that has fixed something that would keep me going for years. There are a lot of little things that happened in my life that, yeah, I could have done differently but actually I’m very lucky man. I have a wonderful family. My two adult daughters both have done very well in life. My eldest daughter and her husband blessed me with two wonderful grandchildren; I have granddaughters. So, I don’t think I have that many regrets, really. I mean, the things that I might have regretted are fixed. I’m a very-very lucky man to have got what I got: To be in the right place at the right time because when they chose me to play in Humble Pie, they could have had any drummer in England and they chose me and I was only 16 at the time. You can’t make that up. It was just the most wonderful thing because of what it led to. I have wonderful experiences. All in all, I’m very-very happy to have had the life that I’ve had and long may it last.

When you were going at The Speakeasy, did you get to meet John Lennon? He was always there.

When you were going at The Speakeasy, did you get to meet John Lennon? He was always there.

No, I never did. The only Beatle I never met was John Lennon. I’ve met the other three. Paul McCartney, I’m lucky enough to have met on a few occasions, because our guitar tech after we split out the first time went on to work for Paul for 45 years and as a result of that I got to meet Paul. He is a very-very nice, charming man. I went to George’s house, the Friar Park. I’ve met Ringo on a couple of occasions. I played tambourine on a couple of tracks on George Harrison’s “All Things Must Pass” album and I met Ringo while we were recording that, but I never met John.

Did you meet Eric Clapton during those sessions?

Yes, I did. I met Eric on a couple of occasions. Again, a very nice man. He always treated me like he has known me all his life. He was always very nice.

Are you proud that you played on “All Things Must Pass”? I’ve talked with Alan White from Yes and John Lennon (“Imagine”) and he played on “All Things Must Pass” too.

When I was there, Ringo was playing drums and I was playing tambourine. When I was there, Alan wasn’t playing that day, but if he is credited as playing on it, I’m sure he did. When it was first released, Peter Frampton and I, were not credited and then 30 years later when they reissued it, as a new remastered version, we finally got our credit on there. So, it took a few years, but we got out finally our names on the credits (laughs).

I asked Alan White in 2012 why Peter Frampton and Phil Collins were not credited.

I asked Alan White in 2012 why Peter Frampton and Phil Collins were not credited.

Was Alan credited on “All Things Must Pass”?

Yes.

Ok. And what did he say?

“I don’t know”.

He was right (laughs). I knew Alan from way back. He was in Bell and Arc when they were opening up for Humble Pie on Humble Pie’s very first English tour. The band Alan was in at the time, I think they were called Bell and Arc and Graham Bell was the singer.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Jerry Shirley for his time. I should also thank Mr. Steve Karas for his valuable help.

Order “The A&M CD Box Set 1970-1975” here: https://www.amazon.com/CD-Box-Set-1970-1975/dp/B0BH6GQPM2

Official Humble Pie website: https://humblepieofficial.com

Official Humble Pie Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/humblepiemusic