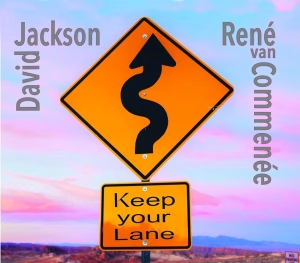

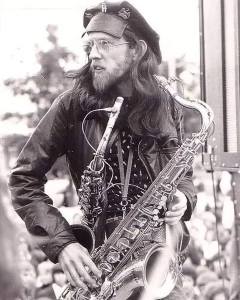

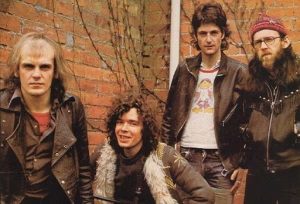

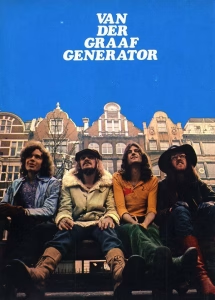

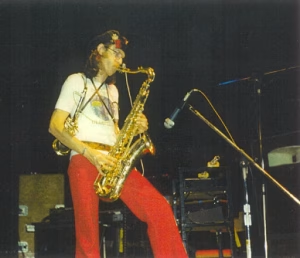

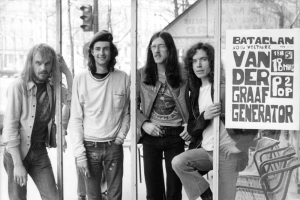

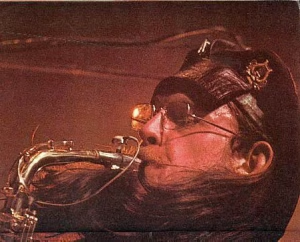

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: April 2024. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary musician: David Jackson or Jaxon. He is best known as the saxophone and flute player of progressive rock pioneers Van der Graaf Generator in the ‘70s, recording with them monumental albums such as “H to He, Who Am the Only One” (1970), “Pawn Hearts” (1971) and “Still Life” (1976). He has also played with original Van der Graaf Generator member Judge Smith, Peter Gabriel, David Cross, Fish, Osanna, Le Orme, Alex Carpani Band, Karperkar’s Constant, Jakko Jakszyk and others. In February, he released his latest studio album “Keep Your Lane” in collaboration with René van Commenée. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

Happy birthday to you for yesterday (15 April)! Did you have a party?

Happy birthday to you for yesterday (15 April)! Did you have a party?

No (laughs), I didn’t! On this occasion, I was just with my wife and my daughter, but the weekend we had a big family party. So, we had party just before my birthday.

Are you satisfied with the response you got so far for “Keep Your Lane” album with René van Commenée (drums, percussion, synths) ?

I ‘m very satisfied with the reviews and the comments that people make. They are very good indeed and we ‘ve had many 4 and 5 stars reviews which is fantastic.

“Waving at Strangers” is very cinematic. What inspired you to write this?

Well, I ‘m glad you like the song. It was a tape; I have an old friend called Andrew Keeling who is a guitarist and a composer with a particular interest in King Crimson. He writes books about King Crimson, but he also likes Van der Graaf. He has a band called The Gong Farmers and he has asked me to play on their records, but one day he said: “I have this old track; I don’t know what to do with it. It’s just the guitar part”. I said: “I ‘ll listen. I love your ideas”, so I developed this tune. He said: “I’m sorry, I cannot send you the masters because it was a tape that got lost. I just have this mix”. So, René and I worked to produce a really good sound and then we added lots of things to it. The original composer for just the guitar part was Andrew Keeling, this collaboration, but it was very beautiful.

“Garden Shed” is a homage to Clive Jones (saxophone, flute) from Black Widow. What’s the story behind this song?

By chance, it’s another idea from Andrew Keeling. He had some music ideas and some very good lyrics from Clive Jones. This was a long time ago before 2014 when Clive died. Again, Andrew is a bit like me: He keeps ideas that are unfinished in a box and sometimes looks at them and I’m the same. He had this idea and said: “I have this tune. What do you think?” So, I presented some ideas for him and he presented them to Clive, but within a matter of months, Clive was very ill and he died. So, nothing happened. Ten years later, I decided to take this idea from Clive and Andrew and take it all apart and rebuild it with René. The chord progression from Andrew Keeling was so interesting and the lyrics and the story of the man with the shed, where everything in his private life lives in the shed and it is his escape from reality made a very funny track. So, René and I tried to make it very funny and strange with the chord sequence. It was just imagination really; just unusual ideas and we kept adding things and adding things. It was good fun.

How did you come up with the idea to re-work “Pioneers Over c” (from Van der Graaf Generator’s “H to He, Who Am the Only One” -1970) with Colin Edwin (Porcupine Tree) on bass?

How did you come up with the idea to re-work “Pioneers Over c” (from Van der Graaf Generator’s “H to He, Who Am the Only One” -1970) with Colin Edwin (Porcupine Tree) on bass?

Right. For many-many years, I have loved the piece “Pioneers Over c” that I wrote with Peter Hammill (vocals, guitar, piano) in the very first days that we lived together in a flat, in a bedsitter and we were sharing ideas. “Pioneers” come from way back in 1970 and Van der Graaf eventually made a version of it, which I loved, but it was very difficult music, very difficult to play live, so it was forgotten. There was a project called “Vital” (1978), a live album and everybody who had been in Van der Graaf, came back together the make this live record called “Vital’ and someone said: “Let’s play ‘Pioneers Over c’”. So, we played “Pioneers Over c” at the Marquee Club in London, but there was problem with the tape machine and the saxophone tracks were not recorded. So, I felt a little bit sad that all these years of waiting for a live “Pioneers” and then my sound wasn’t right. Guy Evans (drums) did a great job because he managed to salvage the saxophone tracks from the vocal mikes and from other mikes’ spill -we call it “the spill”- but I was a little bit annoyed and I felt I need another go at “Pioneers” so that I can do it exactly how I want to do it. Then René said: “Yes, let’s do it, but we do need a good bass player. I love Colin Edwin” and I said: “I love Colin Edwin and I worked on his record called ‘Twinscapes’” (2014). So, I rang him up and said: “Will you play on our record?” and he said: “Please let me, I want to play on this. This is very interesting music and I know it from a long time ago”. He then played but he’s very-very creative and he gave us not just one bass part but lots and lots of bass parts and lots of ideas. So, René mixed it all together like he mixed all the saxophone, flute, whistle and synth parts. It was really like a massive collage of ideas but the framework for the whole thing was the lyrics and the original music. We listened to the original music, just once and said: “Right. We start again” and that’s how we did it. It took many-many days, no, months, I think, but we were working in lockdown, so it was no rush.

“Felona” goes back in 1973 when you and Peter Hammill worked some ideas on the English-language version of Le Orme’s “Felona e Sorona” album. Please tell us a few words about this?

Yes, of course I will. Le Orme and Van der Graaf in 1972 were two of the most popular bands in Italy. It was pop music in those days. It was either Van der Graaf Generator or Le Orme or Banco (ed: Banco del Mutual Soccorso) or PFM (Premiata Forneria Marconi), all vying for #1 in the charts. Their big hit was called “Collage” from “Collage” (1971) record again and they made a new record called “Felona e Sorona” and their record company said to Peter: “Let’s make an English version because Le Orme need to come to England and be big in England as well” because they are very-very musical, lovely music and lovely songs. So, Peter took the music and worked on it; they sent me the music in Italian, a copy of their LP and said: “Would you make some contributions and add some saxophones?”, so they would have a big hit for Le Orme, which it would be an English version of “Felona e Sorona” and add flute and saxophone from David Jackson. As it happened, we were very-very busy. Peter did the English lyrics and in the end they said: “Please, will you sing it?” because their singer Aldo Tagliapietra (bass, guitar) asked Peter to sing using his voice but then they decided: “Oh well, maybe we don’t need the sax and flute now and there is no time, David is touring, let’s leave it”, so I was very-very disappointed, as you can imagine, I had done preparation. Particularly “Felona” was a very sweet song for flutes, saxophones and my new sopranino saxophone, so I started working on it. What happened was: There was a bridge between 1973 and two years ago when I started this album and the bridge was two concerts I did with Aldo Tagliapietra: One was in Italy in the Fasano Festival and another one was at a big concert in Mexico City with Aldo and his amazing young band. Because I played all the music again live and rehearsed it with the band, I thought: “Come on, I ‘m going to do my version of ‘Felona’ now and let’s do it”. So, I decided to do a version of “Felona” and René loved it. He said: “Yes, I will make some interesting percussion and add some effects and some harmony”. He put some harmony across it as well. So, again, it was a very creative project for René and I during lockdown.

Are there other projects you are currently involved with?

Are there other projects you are currently involved with?

So, yes. In this spring (ed: of 2024), I ‘m working on several projects. My most urgent one now is a new record by Dorie Jackson, my daughter; she is making a new LP with the musicians from Karpekar’s Constant, which is a band that I really love, I have played lots of concerts and I have played on all of their records, but they are now writing a folk album just for Dorie and I’m playing some flute and some whistles, some gentle parts, not big sax parts. So, I’m working on Dorie’s new LP and CD and I’m working on a new project with Judge Smith. Judge Smith was the founding member (ed: drummer and vocalist) of Van der Graaf Generator and I have worked with him for a long-long time, between 50 and 60 years and this is a very interesting project called “The Overstayer”. It’s about people who come to countries to escape problems and then they get sent to, they can’t stay to the country they want to be in and they have to be. It’s the everyday problem we live with today and I’m sure you know it in Greece with people who are coming to Greece in boats, we have people coming to England in boats and these people are very talented: Doctors, teachers, all sorts of creative people and then we have to send them away. So, Judge has written a very interesting project about this called “The Overstayer”. You know, how do we help these people with big problems? We don’t need to turn everybody away. We need people, we need to help people. That’s that record. I have two other projects: A project with a guy in California called Don Falcone, I ‘m working for him. I ‘m working for a guy called Clint Bahr in New York. Both of these artists appear on my website as people that I have collaborated with before and I have also some gigs in Italy coming up with Italian bands because always I work with Italian bands. I’ve just come back from Germany with the Alex Carpani Band, and it was a special project with three saxophone players (ed: himself, Theo Travis and Alessio Alberghini) which is amazing. It is a dream for me to play with other saxophone players because I always write so many saxophone parts. I can hear my ideas live for the first time.

I really love the “Another Day” (2018) album you did with David Cross (King Crimson –violin). I ‘ve talked with him, too. I talked with him during the first lockdown.

Oh, really?

Yes. At the moment, I am transcribing an interview with Mel Collins (King Crimson, Camel, Roger Waters -saxophone). It’s 62 minutes long. I’m 42 minutes in.

Amazing, amazing instrumentalist. Great player! Great saxophone player! He works a lot with an old friend of mine called Jakko (ed: Jakszyk -King Crimson’s vocalist and guitarist).

Could you describe to us the musical vision you had on this album, “Another Day”?

Yes, a very good question. David and I first met in 2010 and we didn’t know each other, but we knew of each other. I know David Cross and his big reputation and he knew about me and we met in an emergency situation: There was an Italian band who needed some musicians to play a concert with an American musician called Trey Gunn (ed: King Crimson member from 1994 to 2003-Chapman Stick, Warr guitar), but Trey Gunn couldn’t come. So, they said: “Ok, let’s get David Jackson and let’s get David Cross to join this Italian band to play this big festival in Verona”. So, we met at the airport and immediately we became friends. It was a magical encounter because we are the same age, we have a similar story, he is with King Crimson and I am with Van der Graaf. We are both soloists. There was a big hole in the programme of the festival in Verona. So, David said to me: “Do you improvise?” and I said: “Of course, I improvise” and he said: “I do, too”. We talked about a plan and we had to make up an extra half an hour’s music for the programme. So, we decided to just go on stage and be very funny and very creative and we played half an hour’s complete improvisation and it was a big success and he said: “We must do it again”. So, from that day almost every few months we met up, we improvised and recorded everything and after a few months we had a big mountain of interesting music. We used to meet and we call it “back compose”.

We ‘d find an improvisation that was really strong and we would edit it and make a piece and maybe add extra parts. When it was very strong, we would then take it to an amazing rhythm section: The bass player, Mick Paul, who is a fantastic 6-string bass player and a drummer who is called Craig Blundell (Steven Wilson, Steve Hackett) , who is a very-very strong famous drummer and we went to the studio and we gave them the improvisations to play to, but no rehearsal. It was a very strong method. The only problem with the project was David Cross was always very busy and it took several years for the record to be finished, because he had an other priority and an other priority and an other priority. But there was a special opportunity in this record because there were some technical problems over the sound and the different studios, so, I asked my son, Jake Jackson (Mark Knopfler, Hans Zimmer, Howard Shore), who is a very-very well-known and very strong engineer/producer would he help sort out the problems. So, he took the album with all the recordings and remastered some of the drum sound, re-played the drum sounds with triggers, amazing skill and technology, so, it sounds like it was all done in one studio, but it wasn’t at all (laughs). He made a very-very strong album out of all the ideas we had.

We ‘d find an improvisation that was really strong and we would edit it and make a piece and maybe add extra parts. When it was very strong, we would then take it to an amazing rhythm section: The bass player, Mick Paul, who is a fantastic 6-string bass player and a drummer who is called Craig Blundell (Steven Wilson, Steve Hackett) , who is a very-very strong famous drummer and we went to the studio and we gave them the improvisations to play to, but no rehearsal. It was a very strong method. The only problem with the project was David Cross was always very busy and it took several years for the record to be finished, because he had an other priority and an other priority and an other priority. But there was a special opportunity in this record because there were some technical problems over the sound and the different studios, so, I asked my son, Jake Jackson (Mark Knopfler, Hans Zimmer, Howard Shore), who is a very-very well-known and very strong engineer/producer would he help sort out the problems. So, he took the album with all the recordings and remastered some of the drum sound, re-played the drum sounds with triggers, amazing skill and technology, so, it sounds like it was all done in one studio, but it wasn’t at all (laughs). He made a very-very strong album out of all the ideas we had.

Did you enjoy making “Prog Family” album with Osanna (as Osanna Jackson -2008)?

Of course, I did, that. That was very-very special time for me because I ‘ve been playing with Van der Graaf in 2005, I went back to Italy and the Italian public said: “Ah, David is alive! He is still alive!” (laughs) and the band Osanna had a manager, a very good manager, called Sergio Blue Sky and Sergio came to see me and he said: “Would you like to play with Osanna because Osanna want to make an album called ‘Prog Family’? They would like you to join the band for ‘Prog Family’. They ‘ve been working with David Cross and some other people”. Now, that was a coincidence because that was before I met David Cross. That was in 2008. So, I said: “Ah, David Cross?! So interesting”. So, I went to Naples and recorded, I think, 12 tracks. They sent me the music to prepare. It was five very-very tough days in a studio playing all of these very hard tracks, because the music from Osanna is very tricky, is difficult but I practiced like mad, I played the record and maybe I drank too much coffee (laughs). They were saying: “David is getting tired, give him another coffee. Give him ‘un altro caffè’. Immediately”. So, I had a lot of coffee and I played the record and then immediately Osanna said: “Come on, let’s tour”. So, we played lots and lots of concerts for Blue Sky and we even went to Japan, South Korea, Mexico, we went to many places with the “Prog Family”.

What is like to be a rock star in Italy?

(Laughs) Can I just tell you one more thing about Osanna because it’s very interesting? Osanna had a very great saxophone player called Elio D’Anna and he has stopped playing the saxophone, but I was a big influence on him. So, in a way, he copied my multi-saxes: One, two, three saxophones (ed: played at the same time). Because I was very famous and a rock star in Italy in 1972, Elio D’Anna from Osanna really sort of copied me. Now, I didn’t know this but Lino (ed: Vairetti -vocals, rhythm guitar) from Osanna told me: “You are the only man who can play the parts of Osanna because they were written in your style”. So, when I came to Osanna, they were very tricky saxophone parts that I listened to from the older days and then I recreated, but I was able to play them really quickly and play the original sound of Osanna, but only I did my way. So, in a way, being a rock star was what Osanna had with Elio but they wanted me, too. I tell you, when I went to Italy in 1972 I was on the front page of every single music paper and even local papers. We used to play in a town and there would be a picture of me, always me, with the saxophones, which was a little embarrassing because I am not the singer and we had a very-very strong singer. But there was a slight problem because every record company wanted “Theme One” to be the single, which was an instrumental song. So, to sell the record they had to use pictures of me. But it was quite common for us to do very long drives between Italian towns on tours, but I could get out of a car and go into a café for a coffee at 6 o’clock in the morning and people would shout: “Jack-son! Jack-son! Jack-son!” and I pretended it wasn’t me (laughs). It was crazy.

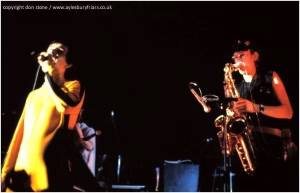

Did you have fun performing with Peter Gabriel at Reading Festival and Friars in Aylesbury in 1979?

A very-very much fun! I have been a big admirer of Peter Gabriel, obviously, because we were “brothers” at Charisma Records, but when he became Peter Gabriel and not Genesis, he was writing such strong material. He asked me in 1979 to come and play with the band, but it was Charisma, the record company, who said: “David can play. You need a sax player for some of these songs. You need a flute player as well for ‘Solsbury Hill’ and other songs like that. David can do it”. So, I went to play with the band and we rehearsed with the band for a week, which was the most interesting experience I have ever had, because in the room was Phil Collins (ed: Genesis -drums), John Giblin (ed: Kate Bush, Phil Collins, Simple Minds -bass), Jo Partridge on the guitar, very-very great musicians. But they were all connected to each other; they all had MIDI devices and Peter Gabriel would come in with a rhythm and a MIDI machine and they would all download this MIDI drum part, put on headphones and listen and then they would start playing a very catchy rhythm and Peter would start introducing the chords. And here is the song “Biko”, this man (ed: Steve Biko, South African anti-apartheid activist, assassinated by the police) is in the news, on the radio, in the newspapers, about South Africa and Peter is writing his song “Biko” literally in front of you.

Then we played all the old familiar songs but I did a lot preparation and I enjoyed playing my style, my way, with the band and it was a wonderful opportunity. Several years later, maybe twenty years later, a friend in Japan wrote to me and said: “I found a recording of the concert, do you want it?” I said: “Yes”, I didn’t know there was a recording, so he sent me from Japan a recording made by BBC of the concert that I played with Peter Gabriel and it was a very treasured experience to hear how my double saxes fitted with Peter Gabriel. Very different sound for Peter Gabriel but it fitted at that time. I think it fitted the songs really well and it’s sad he didn’t ask me again. I was too busy when the record came (ed: “Peter Gabriel” or “Melt” -1980). He said: “Are you available?” and I said: “No, I’m away. I cannot play”, so, someone else played the sax which was disappointing, but this is life. A very strange story, but to add to this, I’ve been working in Italy with a very-very great drummer called Gigi Cavalli Cocchi and he talked about this Peter Gabriel concert and he said: “You know, that was a special day for me. I saw you play with Peter Gabriel, but I must tell you, it was my honeymoon” and I said to him: “You will not believe this, Gigi, but I just got a tape from Japan. Would you like to hear that concert again after 20 years?” and he cried, he said: “Yes! Oh, how wonderful! That was such a great holiday because we were only married two days when I heard that show”. So, that’s a nice story.

Why did you leave Van der Graaf Generator right after the 2005 reunion?

It wasn’t so easy for me at the time, I was really busy, I had a lot of commitments and I wasn’t expecting the band to last. I expected it to be very short. Suddenly, it was different and I wasn’t comfortable with the way things were. I wasn’t on the same page as everyone else; it was all very uncomfortable for me then and we decided that was it. I didn’t want to go on and they decided to go on as just the three (ed: Peter Hammill, Guy Evans and Hugh Banton), but it turned to be a very busy time for me, I had many big commissions to write big works for theatres, for big concerts. So, I was so busy and I didn’t really expect Van der Graaf to carry on, at all. So, it came to an end for me, you see.

Do you remember Robert Fripp recording “The Emperor in His War Room” (from “H to He, Who Am the Only One” -1970)?

Do you remember Robert Fripp recording “The Emperor in His War Room” (from “H to He, Who Am the Only One” -1970)?

In a great detail. We were recording this song “The Emperor in His War Room” and the record producer was a man called John Anthony and he said: “Hey, it’s great but we need some guitar on this track. Why don’t we ask Robert Fripp?” So, Robert Fripp was called, he came to the studio and the studio had a big control room where you could look down on the musicians, but Robert Fripp went downstairs, but we couldn’t find him because he was hiding in a corner, underneath the window. So, someone went down and said: “Are you ok?

and he said: “Yes, I’m fine here”. So, he said: “Where is your amp?” and he put his amp and he put his microphone up with this amp and he didn’t want us to be with him, he said: “Go away, go away”. They had the microphone set up and they said to Robert who had headphones on: “Would you like to hear the track?” He said: “Yes, please”.

So, we sent him the track and he played some amazing guitar on the first take and we had a chat and we said: “That’s great, Robert, we come and talk to you” because you normally talk to musicians about what they want to do”. So, someone went downstairs, I can’t remember, it might have been me, I don’t remember who went down. Someone went downstairs to find that Robert was putting his guitar in his case and he had unplugged from the amplifier and he was about to go and we said: “Is there a problem, Robert?” and he said: “No. I heard it, I played. Did you not record it?” and John Anthony was very experienced and he said: “Don’t worry, don’t worry! Robert has to go. Robert is very busy. Don’t worry, we have it. We have it!” So, we said: “Thank you, Robert, it was fantastic” and he said: “Goodbye” and off he went. So, the guitar playing was the first take. It wasn’t even a run-through; it was immediate. This is the way of Robert Fripp: He doesn’t want to listen to what he plays. He just wants to react completely instinctively to music; that is what you get with Robert Fripp.

Great story! Is it flattering that Iron Maiden’s singer Bruce Dickinson is a huge fan of “H to He, Who Am the Only One” album?

Of course, it’s flattering. Anybody who is more famous than we are, we say, “it’s gold dust”. If somebody says that they like Van der Graaf and tells other people, it’s wonderful. Every musician I know has people they admire. I can tell you lots of people, musicians that I admire but if I tell people I admire, I hope that they will listen to them. So, I think people like Dickinson and other people, for example, Johnny Rotten (ed: Sex Pistols, PiL -vocals), he loved Van der Graaf. Quite a few well-known people, including David Bowie of course, said they liked Van der Graaf and hopefully other people will say: “Why? Why do they like Van der Graaf? Ah, yes, they are very different. They are very original, but they are very passionate; what they write about, how they perform is passionate, it’s different, it’s intense, it gives you a new view on music and a new view on the stories that they are writing about”.

Could you please tell us a few words about “A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers” (from “Pawn Hearts” -1971) you co-wrote?

Could you please tell us a few words about “A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers” (from “Pawn Hearts” -1971) you co-wrote?

Yes, I co-wrote it, exactly. I believe quite strongly that everything starts like a seed that grows and the seed for “Plague of Lighthouse Keepers” was a music that I showed to Peter Hammill. I used to play the piano to Peter; it wasn’t easy to show him tunes on the saxophone, although I did show him double horn riffs, but on this occasion, I showed him this very big melody that I had which became the finale of “Plague of Lighthouse Keepers”. Peter was very taken with this melody and he learned how to play it. My idea for this melody is that it changes key every time after it ‘s become strong and settled, the ending of this tune, it will be changing key every time up and up and up. I said: “It’s a little bit tricky to do this and I cannot play it because it’s too technical, too difficult, but I am going to ask: If you like this tune, let’s get some help from Hugh (ed: Banton -Hammond) on this one, so that we can get it developing and changing and climbing up and up and up”.

He liked this idea but I forgot that day and maybe a year later sometime Peter said: “Oh, look, I got these new ideas for the new record” which was a double album, which became known as “Pawn Hearts”. We started working on this piece and he said: “It is called ‘A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers’” and there are lots and lots of different sections, but the finale is that tune that we worked on about a year ago. Then, of course, during the creation of “Plague of Lighthouse Keepers”, I added some more ideas and so did Hugh and so did Guy, so it was very much a collaboration to write that piece of music, “A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers”. Again, a bit like the song “Pioneers” it was difficult to play live because there were so many sections and there was a lot of overlapping: One section is overlapping into the next, a lot of musical techniques that we were pioneering in those days. We were trying to play in a very different way live and it was difficult, especially as we were only four of us by then.

Do you like the version “The Plague of Lighthouse Keepers” you did for the Belgian TV?

Yes, of course. Yes, it’s the only version that I have ever played of “Lighthouse Keepers” and because it was a film, we were able to stop and start. It was a funny session because we didn’t know that that was what we had to do until we got there. I remember: “Ok, we ‘ll do ‘Theme One’” and then they said: “But you are going to do ‘Lighthouse Keepers’, don’t you?” and we said: “What?!” and they said: “Yes, that is the deal, that is the agreement”. “Ah, ok. Can we have an hour to prepare it?” (laughs) So, we prepared it and while we were preparing the music, they were lighting candles and setting the scene for the film. It was great fun to do it because for me it was a lifetime ambition to play “Lighthouse Keepers”, because there were such great musical ideas in it and great melodies and a great story, as well. I thought it would be one of the best things we could ever play, but we only did it once. We never did it live with me in the band, anyway.

Van der Graaf Generator’s cover to George Martin’s “Theme One” (from “Pawn Hearts” -1971) is one of the greatest of all time. How did you decide to cover this track?

Van der Graaf Generator’s cover to George Martin’s “Theme One” (from “Pawn Hearts” -1971) is one of the greatest of all time. How did you decide to cover this track?

Well, it was a joke, really. I tell you, in 1967 the BBC decided that pirate radio was now so strong that nobody was listening to the BBC. They had a thing called “The Light Programme”, the “Home Service” and classical music. But they said: “No, we ‘ll have Radio 1, Radio 2, Radio 3, Radio 4”, now they ‘ve got Radio 5 and Radio 6. But to tell everybody they said: “George Martin (ed: The Beatles producer), write us a good tune for Radio One and we ‘ll call it ‘Theme One’”. Now, every morning, every single morning at 7 o’clock Radio One started with George Martin’s version of “Theme One” and very often Van der Graaf Generator were driving home from the north of England in a car, usually with me driving and always at 7 o’clock I was gonna turn to Radio One and wake up these guys, because they were all asleep and I was driving very fast. “Come on, let’s have ‘Theme One’”. So, we learned “Theme One” off the radio. There was a big Charisma event in Munich at the Circus Krone, it’s a big circus place.

Anyway, all the record company was there, all the German and international Charisma executives were there and Peter Hammill was busy at an interview, but he just wasn’t there. The rest of the band were there waiting and the manager from Van der Graaf said: “Play something, play something. Everybody is here. Peter is coming. Peter will come in a minute. Just play something”. So, we had always been practicing “Theme One” for fun at soundchecks and rehearsals, so we knew it well, we had an arrangement of it that we could play instantly. So, we played it in Munich and there was no crowd there, it was executives and they said: “Oh, that’s fantastic! What a great tune! What is it?” and we said: “It is called ‘Theme One’ by George Martin” and they said: “We want that in Europe. We want you to play that. Record that! It sounds fantastic”. So, literally, we went home, we went to the studio and Peter didn’t even turn up. We recorded it and John Anthony gave it a very special phasing effect and I wrote a cadenza at the end of it, the double horn riff “da-ta/ di-di-diti/ didi-tiri/ DA-DA/ di-di-diti/di”. So, I wrote that and numbers added on, literally on the spur of the moment, it was done very-very quickly. Charisma released it and I think it did very-very well in every country, but in Italy they went crazy for “Theme One” and it went to #1 for 17 weeks, as far as I know.

How helpful was the producer John Anthony to the success of Van der Graaf Generator?

I think he was crucial, in a way, because the only kind of recording that we knew at the time was a thing called “the cassette player” and you pressed the red button and you could record. When you went into a big studio they had a desk with loads and loads of knobs on it, they had loads of big tape machines in another room with a tape operator, someone who was operating machines. Nobody had a clue as to how to record; how to get a sound even. But John Anthony was a very experienced record producer and the recording engineers and tape operators in those days were very young, but they were learning very fast and there were a lot of very good musicians coming in and out of the studio very fast. I mean, one session we did for a band before Van der Graaf, a band called Heebalob, we were working in the studio and the engineers said: “Go in there and play and we will record you, boys. Ok?”

That’s all you did and we said: “Who else is being here?” and they said: “Oh yeah, a man called Jimi Hendrix is here. He did us a record called ‘Are You Experienced’” (1967). So, nobody was recording himself, everybody had a producer. John Anthony also had lots of very good ideas. You could play something and he said: “Go down there into the room and play it and let’s have a listen” and he ‘d suggest something like this or something like that and then he would tell us how to record it. “We don’t need to have the voice at the moment. We just need the sax, the organ and the drums or the bass and the drums and the sax”. He taught us how to record things and in hindsight I think maybe some of it could have been played better or maybe recorded better, but John Anthony captured the spirit or the essence of that moment, that recording. You must know that things were done very-very fast. The whole of “The Least We Can Do” (1970), which became a very successful record for Van der Graaf, the first record that I was in, anyway, and it was “album of the month”, was recorded in four days. It was very-very fast, very exciting but we had someone who was very experienced helping us.

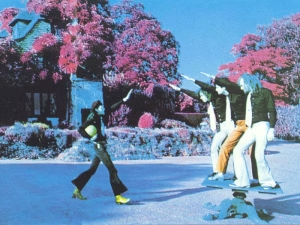

Could you explain to us the meaning of the inner sleeve photo of “Pawn Hearts” with the band performing the Nazi salute?

Could you explain to us the meaning of the inner sleeve photo of “Pawn Hearts” with the band performing the Nazi salute?

Yes, it’s very unfortunate, really. At that particular time, it was very popular to try some phychedelic, it was “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” time (ed: The Beatles song purportedly about the LSD -in fact, it wasn’t) and we had a very-very great photographer (ed: Keith Morris -Marc Bolan, Led Zeppelin, Nick Drake) who did many-many different kinds of photographs and we were really getting very bored: “Oh God, no! This is silly!” and he said: “Don’t worry, it’s all going to be psychedelic. It’s all going to be psychedelic, the colours are going to be pink and strange. Do something different!” and we started talking about the statue in Germany in a town called Kaiserslautern and we were playing a German tour in 1970 there and we remember waking up in a hotel room where we were all together, in a big dormitory. We opened the window in the morning and there was this statue, a Nazi statue, which it looked exactly like that. “Hey, man, let’s do Kaiserslautern” and we just literally did that stupid picture and then forgot about it. When all the photographs came out, the record company looked at all the photographs and said: “It’s a double album, we need a big picture”. This is the house of the manager and of all the pictures and portraits, they didn’t like anything; that’s the only one they liked.

In those days the record company decided everything. They liked the picture, they said: “This is very strong, it’s very strange. People will be talking about this”, but they are still talking about it and it’s a little bit embarrassing. There is another reason for its importance and I had written a very long track, because “Pawn Hearts” designed to be a double album –right- with Van der Graaf and then solo tracks and my solo track was something that I’ve written with Peter Hammill and it was a big anti-fascist anthemic piece to try and neutralise the Blackshirts. The Blackshirts was a very strong movement at the time, very racist movement and it was very unpleasant and I had this idea of writing an anti-Blackshirt thing and Peter was in agreement with this; the thing that he wrote some amazing lyrics for me. We never did it in the end. We never ever finished the recording, because we were too busy and the record company said: “No, it’s not a good idea. These solo tracks they are not going to sell. They are a bit strange”. They are all very strange, to be honest with you. They are four very strange long tracks, they were not finished and the record company said: “Let’s just leave it as it is and we will put that picture on the middle” and it’s there now. It’s a bit embarrassing because I’m still trying to explain it to people and it’s difficult.

You also played on Peter Hammill’s “The Silent Corner and the Empty Stage” (1974) and there is a great story about Randy California (Spirit -guitar) recording “Red Shift”. Would you like it to share it with us?

Of course, yes (laughs). You are really asking some funny things. Randy California came to play on “Red Shift” and the session was nearly finished and then he came, he arrived and he had amazing cowboy boots, amazing clothes and he looked amazing and he carried with him an enormous brown bag and he had in his belt a very-very big bowie knife, which is quite frightening, you know, it’s a very strong, big long knife. He looked a little bit -we say in English- “under the weather”, he looked a little bit tired, a little bit worn and he said: “I just need to rest for a while” and then he sat down in the middle of the control room and opened this big brown bag and it was full of enormous beautiful lemons and he said: “Have you got to play?” Nobody’ s got to play, so he just put the lemon on the table, took the knife out of his belt and cut the lemon in half, he then put the lemon into his mouth and completely ate everything out of the lemon. Then, he ate the other half and then we went on and on and on, eating the lemons and everybody was thinking: “I can’t believe it! How can you eat lemons like that?”, because it sets your teeth on edge; you can’t even watch it and we just watched.

It turns out that lemons are full of very concentrated Vitamin C and Randy California was very famous for taking a lot of drugs in those days and we thought that the only way he could stabilise himself and his body was by giving himself enormous quantities of Vitamin C, which he did. Once he got himself stabilized, he got up, got his guitar and played an amazing guitar part and a little bit like Robert Fripp from earlier, once he had done that, he packed away his guitar, put his knife back in his belt and ran away and that’s it. It’s just like someone from another planet coming, playing amazing music. A very strange-looking man: Very strange clothes, a big knife and a bag of lemons and Peter said something about “lemon hemispheres” or something. He wrote a story about it or a song about it, I can’t remember, but it was a very-very striking experience, a bit like playing with Robert Fripp. The guitarists were not a big part of Van der Graaf until Peter himself started playing guitar, of course, obviously, he later on decided that he wanted to be the electric guitarist in the band. So, he did that himself, later on.

How important is improvisation to you?

How important is improvisation to you?

Good question. It’s something I ‘ve done since I was very-very small. I remember learning to play a little wooden flute when I was 5 years old and as soon as I learned to play tunes, I tried to play the tunes I knew which were very simple nursery rhymes and they were very good exercises because they have all this fundamental interval that we use like “Twinkle, Twinkle” (ed: “Little Star”), with fifths and sixths and so on. As soon as you ‘ve mastered the intervals and you realise that you could play in different keys, for me, my next step was: “Oh, I want to make my own tunes up”, so I didn’t call it “improvising”, I called it “making up tunes” and that is something really that I’ve done all my life, particularly on double horns. I really like to play double horns because it gives me a very strong powerful sound and it’s quite easy for me to make up a new tune every day and so many of Van der Graaf parts or parts of my own music were literally improvised like the end of “Theme One” you have: “Da-da/ di-di, di-di/ didi”, the double horn riff and so many of them. There are a lot on my new record “Keep Your Lane”, a lot of improvised double horn parts that eventually ended up especially in “Garden Shed” and so on. They are just improvised parts. Again, with David Cross, he is an improviser, always has been, always will be. It’s just a wonderful thing to do. I mean, I studied and followed many-many jazz musicians who are masters of improvisation well beyond me, but they encouraged the spirit of improvisation, which really comes from jazz, but of course, it’s in folk music, it’s in all forms of music and it’s been creative and I enjoy it and love it. I love to do it, especially with other people, as well, so you don’t know what is coming and you are really on the edge of creativity.

How much impact did Rahsaan Roland Kirk (saxophone) have on you as a musician?

Enormous influence, really, because when he was so famous at that time, you have to know that I was at a boarding school and my experience of records was on the radio, when I was secretly listening to the radio or I was going to the town to look in the record shop, so that was all that was: There was the radio and there was the record shop. Well, Roland Kirk was on the radio with a song called “We Free Kings” (1962) and that was a great track. Before that, I had been into “Take Five” by Dave Brubeck. I just followed the hits really; these were hit records then. Again, it was before Radio One, it was light music, so I had been listening to the BBC, it might had been on the BBC, or it might have been on Radio Luxembourg or the pirate radio things that I used to listen to when I was young. So, I heard the music, but I saw a picture of this guy, Roland Kirk, with all the saxophones around his neck. I didn’t even know he was blind at the time; it was a revelation that the man was blind, that he could do all that and not be able to see. I had a saxophone at this point, so I knew they are quite complicated, needing looking after and adjustments.

How could you do that when you are a blind, let alone play one, two, three at the same time and playing these amazing tunes? But I think what it was amazingly special about him was the fact that he made every record sound different and he made all these amazing sounds out of the saxophone. Then, I think that’s probably what I have tried to do with the rest of my career, with electric saxes and especially with these later albums. I mean, I played hundreds and hundreds of different parts with as many different sounds as I can possibly create. For me, the saxophone is one of the most creative instruments there is and second only to the voice. When you think about the human voice, it’s the most diverse instrument that we know, from sopranos to basses to choirs. The human voice is infinite in what you can do, that is virtually infinite and the musical instrument that comes closest to the human voice is the saxophone, in my opinion, and Roland Kirk was the best exponent of diversity and creativity with the saxophone and a total inspiration and I’m still exploring his work to this day. I have even seen film of him now which of course I never did.

Are you optimistic about the future of progressive rock?

Are you optimistic about the future of progressive rock?

I suppose I am. I hope it won’t die out. I can give you an example why I’m optimistic and particularly in Italy; it’s very strong in Italy. I remember playing with Osanna in the north of Italy and a man came to me and I look at him and I thought: “Well, hang on, he must be 60, yeah, he’s 60” and he said: “Hello, I came to see you, I stole my father’s motorbike and came to see you at this concert. Here’s my father, he has forgiven me. Here is my son and here is my grandson” and I’m looking at four generations of the same family and every single one, they wanted to shake my hand and I thought: “Thank God, this is the future of progressive music in Italy” (laughs). It is a family affair, like the “Prog Family”, it’s a family business. You know, people share the music that they love with the generations above and below them. That isn’t quite the same I ‘m afraid in England, I don’t know if it’s the same in Greece, tell me.

They listen to enough of pop music, but there is also Greek music like zeibekiko, in 9/8 time signature.

I agree with that. For me, prog music is still alive, I ‘ve just come back from Germany and many people in Germany have come from all sorts of different countries to the festival. So, it’s an international music with people who are very-very loyal to it. My first degree when I went to university was psychology and I studied imprinting and I think many-many young people in the ‘60s and ‘70s, they imprinted on progressive music: Idols like Jethro Tull, new sounds and they would take that sound and that idea and keep it going. But I don’t suppose it will last forever because no music style lasts forever; it’s fashion, unfortunately and business. Progressive music was successful in the ‘60s and the ‘70s because of the businessmen, who made money out of progressive music, but there aren’t so many businessmen now who can make money out of it, so it has become more of an academic, more of a personal passion, but I don’t know if it will survive, you tell me.

I hope so.

I hope so, too (laughs), of course.

Is your hat a German train driver’s one?

Is your hat a German train driver’s one?

No (laughs), it’s not. At that time in 1971, I had a girlfriend and she liked the hat of our drummer and she tried to make a copy of the leather hat of the drummer. She made it and in her opinion it went terribly wrong and she became very angry and threw it away. Now, I said to her: “Look, that’s a great hat. Don’t throw it away. If you don’t like it, can I have it?” and she said: “I don’t care, you can have it. It is rubbish”. Anyway, I liked it and it was very comfortable; it was the perfect size. I put it in my head and I felt comfortable. It has very big leather top and when it came over my head and over my ears, it was like when you put your hand behind your ears, so you could hear someone better. When you put your hand behind your ears, that is exactly the feeling that I have when I put the hat on. So, for me, it meant that I could hear myself better. I can hear myself better in the room or wherever I was practicing so I became crazy about the hat. I used to wear it all the time, because I could hear myself better.

When I was playing on stage, it was even better still, because there were no monitors in those days; it helped me hear everybody else better in the band, particularly the singer, so I could hear what Peter was doing because we had a backline. I had a big electric backline and it kind of protected me a bit from my own sound and meant I could hear the other musicians better, but most of all it was a lucky hat because I put it on and on 1st May 1971 they took a picture of me in the hat and they put it on the front page of the Melody Maker and for the next year I became an icon and image, “the man with the hat”, funny hat, that no-one had ever seen before. It was also very comfortable to wear it and you got hot and I used to have problem with sweat coming in my eyes, but that peak was brilliant because it was like a gutter for the rain and the sweat didn’t come in my eyes, it ran down my cheeks, so it didn’t matter how hot I got playing concerts. I didn’t have a problem with sweat getting in my eyes which it completely blinds out when you get like that. It used to happen, so for many reasons the hat became an icon and now it’s a sort of superstition for me: If I lose the hat, what would happen to me? Oh, my goodness!

Did you enjoy the Van der Graaf Generator tour of Northern Europe with Alexis Korner in 1976?

Yes, I did very much because I’m a very big fan of Alexis Korner. I had some of his records and the blues music was a very important transition for me. When I was at school I played traditional jazz, we called it “trad jazz”, I played with a blues musician and there were all these different styles of music: There was English pop music like Georgie Fame. Pop music was taking from the blues and jazz, it was taking from different styles. But he was a great star and a very nice man. It was one of those tours where you go and listen to the band and then you play. For him, to be supporting us, was wrong, really, but he was the better man. In my view, he was a more important musician.

Did you get to know Robert Wyatt (drums) when VdGG toured with Soft Machine?

Did you get to know Robert Wyatt (drums) when VdGG toured with Soft Machine?

No, I don’t really remember meeting him, to be honest with you. I know the name and maybe somebody said: “That’s him” or I saw him, but I didn’t know him.

With Jimi Hendrix when you were in the same studio?

No, we didn’t meet. We didn’t meet, unfortunately. I ‘m sorry about that. There are lots of people I really wanted to meet and never did.

What was your reaction the first time you listened to The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper” (1967) album?

Oh, it was wonderful. It was a good time for me, I was at university and I had some very good friends. I lived in a big residence and I had some good musicians living in the rooms near me and we all used to share records and listen to records. We all had record players to play our vinyl records and my friend who was a good guitarist was teaching me to play the guitar. I got a guitar for my 21st birthday from my family. They said: “What would you like?” and I said: “I want a guitar”, so I learned the guitar but while I was learning the guitar with help from my friend, he said: “Look, this record is called ‘Sgt. Pepper’” and it amazing, everything changed in an instant. My God!

Did you like other saxophone players from you era like Dick Heckstall-Smith (Colosseum, Graham Bond Organisation)?

Yes, I did. I did like him and I met him and I was talking about him in Germany. He was a great bluesman and a technician, a great jazz musician as well. He used to play two saxes but he wasn’t really the influence, he didn’t influence me. I didn’t feel I was influenced by him. I think he was a sort of parallel: He was going that way, I was going this way. I was going into a much more modal direction for playing fours and fifths rather than thirds and the harmonies and things in the phrasing that he was doing. Van der Graaf really did shape my double horn playing; I had been trying all sorts of different styles and all sorts of different keys, but the moment I was in Van der Graaf, I had arrived. All the practicing I had done was for Van der Graaf, even though I didn’t know I was doing it.

You experienced some very wild situations with Van der Graaf Generator in Italy in the ‘70s. What stands out the most?

The final tour, really, in 1975. It was the whole situation that year. There was the concert in Padova. That concert. The whole tour was crazy because Van der Graaf were very-very big but the politics were very-very aggressive in those days between the fascists and the commies and promoters had to align themselves with the fascists in order to do concerts and there were thousands of people there in sport stadiums, so it was a good place for politics, for political speeches and then the communists all they wanted to do was to cause a fight and shut down the concert. So, there were these events that everything went wrong, really wrong, until all our gear was stolen and we were shut down. It was very-very chaotic and very frightening. That’s all I can say, really. There are many detailed stories of what happened, but yeah, it was very-very hard.

Do you think because of the streaming services listening to an album for start to finish has become a kind of lost art?

Do you think because of the streaming services listening to an album for start to finish has become a kind of lost art?

(Laughs) Yes, I do. It is a lost art. Yeah, I think it is, but having said that when I left Van der Graaf in 2005, that is what I was doing: I went off to write three big works. People were asking me to write things; it’s called “commissions”. I went off and wrote a big piece called “The House That Cried” and “The Beam Machine”, I wrote “Twinkle” (2007) with Judge Smith. In a way, they were more important to me, as a composer and a musician to have created work for other people. I think progressive music is fantastic, but for me, what came out of it, my success and fame, gave me opportunities to write things for other people to do; to recognise that genre. There are still plans for me to go to Italy to do one of my big works that I wrote in English that is like an album and it’s a big show: It evolves choirs, children to sing and dance and disabled people to perform. For me, as much as I love progressive rock music, it gave me an opportunity to do what I believe is of even more value and that’s right: Big works for other people to do, to be a community musician.

I admire the great composers for the things that they ‘ve written for other people to do. I ‘ve had that blessing, thank God, because of Van der Graaf. Without Van der Graaf I wouldn’t have had the respect, the people wouldn’t have known what I was capable of doing. So, in a way, Van der Graaf has been a sort of stepping stone for me. It’s not the most important thing in my life, by any means. I absolutely love working with my daughter and I love the fact that my son could help me with the David Cross album and really saved that and made it into a great project. The fact that I can do things with other people, not just inside a small band, which is sometimes a bit out of control, which is uncomfortable at times, as I said earlier. Things can get uncomfortable and you need some space, you need to get yourself strong again and not be swept away by something that is out of your control: It’s in the control of businessmen and promoters. Musicians sometimes are in the wrong business and are pawns, they are just being manipulated for people to make money, which is I’m afraid what happens. It’s still happening to this day: Being managed and exploited.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. David Jackson for his time. I should also thank Stevie Horton for his valuable help.

Order “Keep Your Lane” album from here: https://propermusic.com/products/davidjacksonrenevancommenee-keepyourlane

Official David Jackson website: https://jaxontonewall.com/