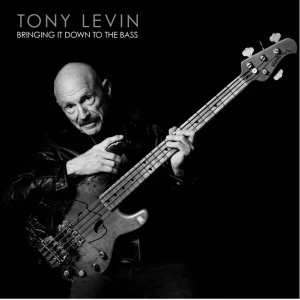

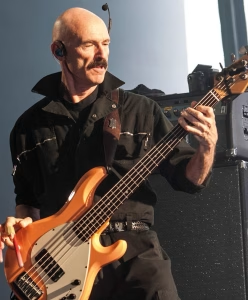

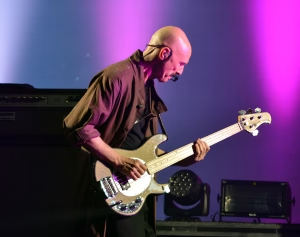

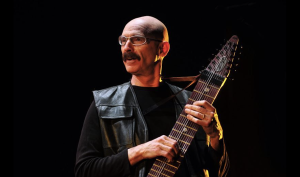

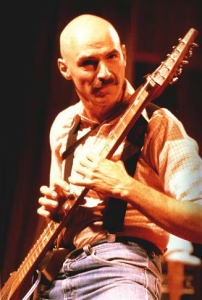

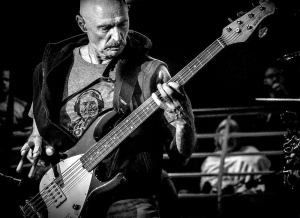

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: August 2024. We had the great honor to talk with a legendary musician and a fine person: Tony Levin. He is best known as the bass player of King Crimson since 1981 and for his work with Peter Gabriel since 1977. He has also been a member of Stick Men (playing Chapman Stick) and Liquid Tension Experience and has played with John Lennon, Paul Simon, David Bowie, Pink Floyd, Tom Waits, Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe, Buddy Rich and many others. On 13 September he is releasing his new solo studio album “Bringing It Down to the Bass” on Flatiron Recordings featuring Steve Gadd, Mike Portnoy, Vinnie Colaiuta, Steve Hunter and others. On 12 September he is starting a US tour with Beat (featuring Adrian Belew, Steve Vai and Danny Carey) performing the King Crimson music from the ‘80s. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

It took you 10 years to make “Bringing It Down to the Bass”. Could you please give us some very basic information about the writing and recording process of it?

It took you 10 years to make “Bringing It Down to the Bass”. Could you please give us some very basic information about the writing and recording process of it?

It didn’t take that long because I was working all the time on it; it took that long because I’m very lucky, I’ve got a lot of great touring to do. That’s my favorite thing: To play live and I’ve had the chance of course to play with Peter Gabriel and King Crimson on tour, with Stick Men and also with Levin Brothers playing jazz, so that’s a very good problem to have, that I would write a piece and begin it, but I didn’t have the time to complete it and especially to get the other players on it. So, in this last year whenever I had a break I was resolved to finish this album before I’m too old to finish it, I’m joking with that. In March, April and May of 2024, I took off from any recording or touring in order to finish this. So, I’m very happy to finish it. Some of the material I wrote quite a while ago and some of it is very new, just from April and May. The name “Bringing It Down to the Bass” is appropriate because a lot of the compositions I wanted to begin with a bass line or a bass sound or maybe a technique of playing the bass, maybe with thumbnail playing or funk fingers playing, not all the songs but a lot of them are like that, but to me that main thing about the album is the other players that I have on it. I have a wonderful group of friends who were able to join me on this and just the list of their names makes me realize that it must be a good record even though it began just with me.

My album “Bringing It Down to the Bass”, when I brought it to the record label, this particular Flatiron Records, I said: “I must tell you that I insist part of the project to me is that I want to take portraits of each bass that I used, not just a picture in the studio, but out in the world that reflects that instrument. That’s artistically important to me, so I am gonna need to have a booklet”. Of course, I ‘m looking forward to the big 12-inch booklet that is with the extended double LP version that will come out sometime later this year, but even in the CD package, I must have a 12-page booklet with these photos and they said: “Sure, that’s fine”. They are a wonderful company that they support my artistic vision. But anyway, the album was intended to be about the bass in more ways than just in the titles of the songs and the fact that we began with the bass parts and I feel good about the portraits that kind of give you a sense of what that bass is like. When you think about it, we, guitar players and bass players, have an interesting relationship with our instrument, because each instrument is in a subtle way different than the others: The sound, the feel, even the physical feel of it. So, that’s a big part of my life and that’s part of what this album is about.

I really love “Me and My Axe”. You can almost sing the melody on this. Please tell us a few words about this great track.

Sure. The name of it is appropriate for the album because we have a relationship with our instruments, of course, even though it’s not a song, you know, it’s instrumental. So, there are no lyrics to it, but I envisioned it as a duet, yes, between me and my instrument, but really in practice between my fretless bass playing the melody and trading the melody with the great Steve Hunter (guitar), The Deacon. We have great history together, me and Steve, because we played of course on Peter Gabriel’s first solo album (ed: “Peter Gabriel” -1977) and we toured with him a lot, but before that we had played together with Alice Cooper on a number of records, so, me and Steve go way back and then I had to think if I’m bringing him, why not I’m bringing in some other alumni of Peter Gabriel band. So, that track is Larry Fast playing the synthesizer and Jerry Marotta playing the drums. In a way, like a lot of the tracks of the album is a bit biographical and a bit historical to reunite these players and the nature of the song is one of my very favorite “voices” on guitar, blues guitar or whatever style he’s playing, it’s just a beautiful sound from his guitar. I had a great fun trading the melody with him and then of course joining together in harmony near the end and that’s my story of the building of the track.

“Uncle Funkster” with Vinnie Colaiuta (Frank Zappa, Jeff Beck -drums) sounds pretty challenging technically. Did you have trouble recording it?

“Uncle Funkster” with Vinnie Colaiuta (Frank Zappa, Jeff Beck -drums) sounds pretty challenging technically. Did you have trouble recording it?

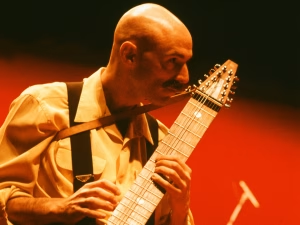

Yes, it’s a very different story. Instead of a composition I wrote, this is a duet, with just drums. Vinnie is one of my very favorite drummers, of course, he is a great drummer and the Chapman Stick which can do very interesting things like a bass; I play it as a bass but it’s very different instrument. For those who don’t know, the Chapman Stick you play it with hammer-on technique, you don’t pluck the strings and it has a very wide range because the bass strings are tuned in 5ths not 4ths, but that doesn’t matter. I envisioned: Ok, I’m gonna do a duo track with Vinnie but instead of getting together in a studio and doing it quickly -because he lives in Los Angeles and I live near New York- I thought a have a new way of recording with drums and bass which it came up a lot on this record. It’s better than just doing the bass part and sending him: “Ok, here is what it is and you play”. So, what I did on that track was, I played the song really roughly the way I was gonna play it and I said: “Ok, Vinnie”, I know his playing of course but I didn’t know what he was gonna do, “you play with this, but if you wanna do something a little different go ahead and do it”. Then, when he was done I took his drum track and I played my part to him. It sounds just like a little minor detail but it’s profoundly different than if I finished my part and sent it and he had to learn it and go through that. In a way, it’s a little bit like jamming together because you both got to play to the other person but you have, in my sense, a composition that’s a product of both of you. So, to me we both wrote that piece, me and Vinnie and yes, it has a lot of ad-lib and a lot of just going crazy on it and that’s what I envisioned for that piece. Also, it’s a nice break from the compositions on the album which have a lot of players to suddenly have this track that’s a jam really for a couple of minutes.

Is “Side B/ Turn It Over” influenced by gospel?

(Laughs) No, I don’t think so. Not gospel, at all. We have a thing in America called “barbershop quartet”, is a style of 4-voice singing with no instruments and I’ve always been a fan of barbershop quartet when I was a kid, I always had a group and what I did incidentally, when I did Peter Gabriel’s first solo album in 1976, I talked Peter into having a barbershop quartet introduction to one song and we did that live. It was a very funny part of that first tour in 1977. Ok, that’s not too much to do with why I wrote that piece; those of us who are old enough to grow up with LP’s, vinyl records, to me there is the experience of getting up and turn it over and not knowing what is gonna be on Side B, the other side of it. It’s more than just a little thing we did. So, I thought about that and I wrote really a poem about it and it ended up lyrics and then I decided to sing that in a barbershop quarter style. Then, because sometimes you get corky ideas that are not the norm, I decided in the middle to have a bass solo, which you do not ever do in that style; in a barbershop quartet you never have instruments. So, it’s a barbershop quartet with a little short bass solo in the middle, just because I wanted to do that and hopefully my poetic ideas about the experience of turning the record over are worth-listening to.

Could we say that “On The Drums” is a kind of homage to the drummers that you ‘ve worked with?

Could we say that “On The Drums” is a kind of homage to the drummers that you ‘ve worked with?

That’s the perfect word. Is it an homage? Yes, it is. It was in the lockdown year, in 2020, when there was not work for us musicians after the spring and we thought: “Ok, what are we gonna do?” I did two things: I put together a photo book (ed: “Images from the Life on the Road”) of some of my very good photos from the road; fine. But musically I didn’t feel like it was my right time to finish the album, so I worked on one piece. I resolved to write a composition using only the names of drummers I have played with. I have played with a lot of drummers, I ‘ve been around a long time, so, there was a lot of material of names, but the names didn’t rhyme, they didn’t have the kind of syllables that make it easy to write a piece. So, you are looking out now at my studio (ed: on Zoom), all over my studio I had scraps of paper with little musical ideas: “Ok, these three names maybe or even one: ‘Colaiuta, Colaiuta’”, I wrote with the accent and I took 9 months to bring them together to be a composition. I didn’t know if it was gonna be a song with a rhythm section playing, but I decided it to do just as a chorus of my voice.

So, it’s anywhere from eight to twelve voices and that’s all. No instruments on it and I think it came out well. I’m happy with the way it came out; it’s a very interesting composition but it’s amusing too, especially if you know drummers, because it’s just one name after another after another and it goes on and on with the names of drummers, but in different musical ways. I have a few other words at the end that says: “On the drums”, which is the title but it’s also the only lyric I sang after the name of those drummers and yes, in a small way, it’s a “thank you” and homage to the many great drummers I’ve been lucky to play with, who have influenced my bass playing, for sure, through the years, since the beginning for me when I was in school. I was in classical music school, at the Eastman School of Music and Steve Gadd (Eric Clapton, Steely Dan, James Taylor), the great drummer, happened to be in school then and he really mentored me in how to play jazz, so, I ‘m especially grateful to him and he has a very nice ballady section of that song.

By the way, I recently learned that Bob Ludwig, the great mastering engineer (Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, The Band, Rush, Bruce Springsteen) was also with you at the Eastman School of Music.

You know that?! I didn’t know anyone that knows that. And he was a trumpet player, a very good trumpet player. I expected to see him in some symphony orchestra, but years after we left school life, of course, he had Gateway Mastering. He was the master of mastering, for sure.

What inspired you to write “Give the Cello Some”?

That was after a lot of compositions that were carefully worked out, really, some for years, I thought I’m just gonna throw in a rock piece and I had some crazy ideas for lyrics. They didn’t begin with that being about the cello, but I wanted to have a cello solo and that led to me thinking: “What is the title?” and I don’t sing, I say some words. We, musicians, talk about the form of the piece. We say: “Let’s do a blues, then you have a solo and then we’ll give the guitar some” or something like that. We speak that way but we don’t put that on the record and I just thought: “I’m gonna leave that on the record: My vocal instructions to the other guys”. So, it’s got some humor to it, but it’s also to me just a simple “rock-it-out”, kind of bluesy song. A short one where I give solos to the cello and to my brother (ed: Pete) on the organ and then, I tell the guys: “Ok, it’s over. One, two, three, four” and then it ends.

“Coda” is very cinematic. What was your musical intention on this?

“Coda” is very cinematic. What was your musical intention on this?

Thank you. I love your questions, by the way. The name says it all. I had in mind to write something quiet -no more rock, there is a lot of heavy rock on the album- to have as the last piece. It was intended from the beginning to be the last piece of the album and I started by playing the piece on piano, some chords, I knew I was gonna solo with my bass over it. I made an error. Any classical musician listening can maybe have a laugh over that. There is a Mahler symphony, the 5th Symphony, that I think the 2nd or 3rd movement ends in a very unusual way, with just the basses of the orchestra playing a E major triad, and I wanted to end with that. It’s just a very fitting way to end a bass album; I thought maybe nobody else has used it (laughs). I wasn’t going to tell anybody about that, but I found out recently I made one mistake: I thought it was E major, but really the real one was D flat major (laughs), so, it was half a tone different. In the beginning I thought: “I am gonna write just a nice piece to end the album, a quiet piece that features the bass and I’m gonna end with this E major triad and I did that and originally, I just played this simple piano part and I played the cello.

I played four parts as a cello quartet, as a background to the bass but I felt like, even though the cello was good the way I did it, it wasn’t just good enough. I ‘m really a bass player playing a cello and some people wouldn’t hear the difference but I kept hearing it and I thought the song deserves better, the album deserves better, so, I know a wonderful cellist, Linnea Olsson, who toured with me with Peter Gabriel. She lives in Sweden and I asked her to play the parts. I had written out the parts and she played them much better. In a subtle way, much-much better than I did, so I was very happy and only one little thing about the credits: She was very pregnant when she did it and I thought it would be appropriate to credit the baby, too, because when you think about it, the cello was leaning against the baby, so, the baby in some way we don’t understand had a little to do with this track. So, in the credits of the album, it credits Linnea Olsson, but also her baby. As you can tell my album is serious, but it has a senses of humor that is always ready to wake up.

Would you like to tour for ‘Bringing It Down to the Bass”?

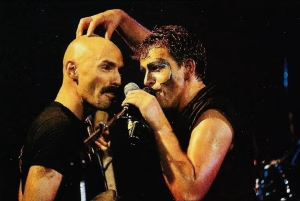

I would like to and I was planning a tour for September. The release date is September 13th and I was planning just a small tour starting then, but guess what? Something came up (laughs) that’s pretty special and I ‘ll talk about that. The Beat Tour, we call it, now 65 shows in the US and we hope to continue it next year, where will we go, I don’t know, whether we can even continue it. Adrian Belew (ed: King Crimson, David Bowie, Frank Zappa -guitar, vocals) got the idea to play the music of King Crimson in the ‘80s, those three albums (ed: 1981’s “Discipline”, 1982’s “Beat” and 1984’s “Three of a Perfect Pair”), not with the original members, but with me, Steve Vai on guitar and Danny Carey from Tool on drums. So, it’s gonna be wild. As I speak to you, we are about to start rehearsing, so, I am gonna see where it goes, but I am practicing the material, right behind my back here, where you are looking at and it’s difficult. Even though, I played the original parts there, there are some very difficult things where I’m playing in two different time signatures at the same time and singing at the same time in a third time signature. So, yes, I ‘m practicing a lot for that; we have allowed ourselves a lot of rehearsing time because we want to really get it right. It’s very exciting now the idea of it and it’s gonna be really fun to see where we take this music. We won’t do it exactly the same but how differently we ‘ll do it is something I don’t know at this point and I’m excited to find out.

Were you surprised when Adrian Belew (guitar, vocals) first asked you to tour with King Crimson’s music from the ‘80s?

Yes, I was surprised and to tell you the truth I was not sure it was for me, I was not sure I wanted to do it. I ‘ll tell you why: Because to revisit music that I did before is not my favorite thing. I don’t dislike it but my favorite thing is to make new music and then tour and to play music that can grow on the road from playing it live, that can grow into something more special than it was. So, that material was great and I didn’t say “no”, but I said: “Let me think about this because I have to be 100% sure about playing the older material”. But then he told me who was on board to play: Steve Vai and Danny Carey and of course like any bass player I want to play with Danny Carey and like any rock player I would love to play with Steve Vai. So, it suddenly became something that made my mouth water, instead of just the idea of playing the material, is a good idea, but it didn’t make my mouth water.

Most of the Beat tour dates are currently sold out or about to be sold out. Did you expect that kind of response by fans?

No, I didn’t but to tell you the truth I didn’t even know that. I knew a lot of the dates were sold out and that’s why they added 22 more shows, but I haven’t followed the sales. It’s management who cares about that and it’s great to hear that people are excited about it. I’m in touch with a lot of fans because I tour a lot. I just finished this tour with Stick Men and afterwards when we were meeting the people who came to the show, there were a lot of them who told me that they are coming to many shows, more than one. Two, three, four, even one fellow said he is coming to six shows, so, that implied to me that the fans -not that there are tens of thousands of fans- are very excited and they are coming to a lot of shows, which is a great thing and reminded me that we should learn more than just one show of material, so that we can change the show some from night to night and not play the same show. So, it’s all exciting and it’s all great but the truth is I don’t really follow the sales and that kind of things. I just focus on the music.

In your opinion what makes the ‘80s King Crimson music that you will perform with Beat still relevant today?

In your opinion what makes the ‘80s King Crimson music that you will perform with Beat still relevant today?

If music is very good, then it’s relevant. We can make it relevant (laughs). It’s a matter of how good it is and now that I‘ve been re-listening -I really don’t spend my time listening to the albums I’ve done- some of these pieces, let me say, I’ve been playing for many years; we have revisited them. But most of them I have not played them in a long time and listening to them they are very radical. Everything about the band somehow -we didn’t plan it that way- each of the four players was doing things that they hadn’t done before and maybe nobody has done before. I was bringing, for instance, the Chapman Stick, I played the Chapman Stick a lot, instead of the bass and I didn’t do that in other bands at that time, so it was probably one of the very first rock bands that featured that on the bass. That was one example. Another is that Bill Bruford just plays drums differently than anybody and differently on every song. He always was surprising you and then Robert Fripp and Adrian Belew each has a unique sound and style on guitar. When you think about, all the great guitar players we know, really, there is only not that big a number of them who have their own sound, that you hear it and you say: “Oh, that’s Robert Fripp” and you hear it and you say: “Adrian Belew”. So, to have two of those guys in one band in 1981 was an unusual thing. Then, you add in the quality of the compositions, a lot of them came from Robert Fripp and a lot of them came from Adrian Belew; both great writers. As I said, I am practicing now, I am revisiting them and they are very complex but they work as compositions. I don’t know what is gonna be like the show and what approach we will take with these pieces, but I know it will be musically worthwhile because the compositions are great and the players are great, so, in a way, we can’t go wrong.

Do you have any personal favorite song from that King Crimson era?

I don’t but let me say about myself that I don’t tend to have favorites of anything. Well, a have a favorite wife, my wife and a favorite daughter, my daughter but apart from that, I have usually basses behind me that I love. I have a wonderful group of basses, but I don’t have a single favorite. I have one that I’m using right now, a little more than the others and the same if you ask me about these great seven drummers on my album, I don’t have a favorite. In music, I always appreciate that there are so many ways to do things that there are a lot of bass players that I love and admire, no favorite, no favorite drummer. Even the acts or tours that I’ve done it’s just not my nature to pick a favorite.

Will there be room for experimentation in Beat concerts?

We haven’t rehearsed yet. We are only a few days away from beginning rehearsing, so I’m not sure what the show will be like and which pieces will do. I can almost guarantee that there will be improvisation and experimentation and some of the compositions, for instance, “Indiscipline”, which starts off with a very simple rhythm on the Stick only and the drums go on for as long as they want, just playing, so, that alone has a lot of improvisation for the drummer, but I can guarantee there will be improvisation, whether there ‘ll be a specific piece where we just play something different every night, I don’t know yet. I think probably there will be.

Are you looking forward to going to Beat rehearsals to see what your interaction with Danny Carey will be like?

Are you looking forward to going to Beat rehearsals to see what your interaction with Danny Carey will be like?

You are exactly right. I’m excited about it, it’s only a few days away and I’m sure it’s gonna be good. But we think about it, this is what we live for, we bass players: Play with a really great drummer that you haven’t. I have played with Danny a little bit when he sat it with King Crimson, but I haven’t really played with him, with just the two of us. I’m very excited about it, it can’t go wrong, I know it’s gonna be great but I don’t know exactly what it will be like and I am looking forward to it.

Have you heard anything about European tour dates of Beat?

No, I haven’t and I asked, because I love to tour Europe, really love it and I don’t get to do it as much lately and I treasure the time that I go there. They are looking at next year and they have not mentioned that Europe is a possibility, so, always ahead of time, we, rock musicians, can’t say what’s really gonna happen but I can say, for sure, unfortunately, there is no plan to come to Europe at this point.

I know it’s too early now but would you like to create some new music with Beat in the future?

Yes, that is also has not been discussed, but we have talked about at what point we should record the show and let that be out to the public. It has not been discussed and I’m gonna see if it will be discussed. Really, when you have a band like this, that it’s not guys who are full time in that band, the situation you always run into is that the players who are in other bands, with Danny, for instance, who is in Tool, so, when Tool tours and writes their albums, he can’t tour with Beat and if I’m in King Crimson and if I’m out with Peter Gabriel, I can’t do it. So, the time frame becomes critical. That’s why it took us so many years. I think Adrian has been planning this tour for four or five years. Really, he started early but between the lockdown, the virus and then schedules of people and be sure you have the right people; Steve Vai is also extremely busy on his own, we don’t know when we have time. So, what I know is that we tour the rest of this year, we will do these 65 shows and we will probably do something but I don’t know where in Spring of 2025 and beyond that, I don’t know. I hope we will. I hope we will do it all: More touring, writing and recording.

Are you satisfied with the end result of “In the Court of the Crimson King: Crimson at 50” (2022) documentary?

Are you satisfied with the end result of “In the Court of the Crimson King: Crimson at 50” (2022) documentary?

(Laughs) I don’t think the expression “being satisfied with it” has anything to do with how I am about it. I saw it, like the fans, when it came out and I was amazed by it, it is quite a documentary. It’s very heavy, very funny and I felt it shows the drama and the heaviness of King Crimson, but it also shows the humor that is backstage that goes on; it showed that very well. The truth is I was only involved in the humor and in the music, in the intensity of the compositions and in playing shows. I never got involved in the drama that I know now about (laughs), because I saw the documentary. So, I was like anyone who didn’t know much about King Crimson, I was amazed at how heavy some of the history was, that I stepped into without realizing it and also I’m very aware that all my years in the band I wasn’t involved in the heavy drama.

Was the three-drummer line-up of King Crimson a bit extravagant?

I’ll tell you the real story: With Robert Fripp, I learned early on to have a big respect for his vision of what King Crimson could do and it’s amazing when you think about it. He also had a lot respect for how I play the bass parts on my own. In the ‘80s it was not a factor, we did what we did. In the ‘90s, he came to me and he said: “You play the Chapman Stick, but I am gonna bring in another Chapman Stick player, Trey Gunn”. My thought was: “That’s not a good idea if that means each has to play half as much, plus this is not a guy I know, at all”. But because Robert’s vision is really what King Crimson is, I took a deep breath and I said: “Well, I’ll not only do it, but I’ll try to make it musically great”. What I didn’t know, Trey Gunn wasn’t just another Stick player; he is a great musician, he was very sensitive to what I am doing, so, Trey and I worked very hard. It wasn’t easy but we found mechanisms for the two of us playing what one person would have played before. So, as usual with Robert the idea was radical and it wasn’t what you expect and it caught me off guard but when I went with it, it was ok.

Now, 15 years later, Robert called again and said: “I have an idea: Three drummers” and it took my breath away and I didn’t say, but I thought: “That’s gonna make things very difficult for me. I’ve got to play a lot less. I’ve got to change my sound a little and roll off a little to the low end”, because it’s gonna be so much going on down there. But of course I said: “Yes, I’ll do it” and again I didn’t realize that the three drummers he chose didn’t just clatter away and all play a drum part, they worked out in elaborate devices and ways; new ways. They reinvented rock drumming for three drummers and found ways that not clattered things up. In fact, I not only could keep my same sound but I played a little busy or a little more than I had with one drummer, because I sensed that there was space for that. So, to summarize all of that that I said, through the years I’ve learned to respect Robert’s vision of what King Crimson could do and also understand that he is very good -brilliant, really- in finding the right people to implement his vision, the right players. He doesn’t just impose the idea on any players.

So, is Robert Fripp an easy-going person to work with?

So, is Robert Fripp an easy-going person to work with?

Now, the people that ‘ve seen the documentary, they ‘ve seen the humor behind the scenes that Robert has, because even we were doing very serious King Crimson shows and they are serious (laughs), especially the 3-hour concert that we did for years and took a lot of concentration and energy for us, but at the same time backstage we were joking around and it’s really a relaxed band, in that sense, when we are not on stage. So, there is that side of Robert. Also, there is the very intense, demanding side of him but he is not that way with the other players. So, to be in the band with him was always easy for me and also Robert is a unique person. He behaves differently than a lot of other people but it’s very consistent. I learned, for instance, when we are on the road and I see him in the hotel breakfast place, I know he’s listening to music and forming a setlist for the next day and he doesn’t want to share breakfast with me, so I sit at a different table. I don’t mind that, but the good thing is he is consistent, it’s not like sometimes he would wave me away or something. It’s just the way he is and it’s easy to get along with people at are consistent in their behavior.

By the way, Mel Collins (saxophone, flute) told me in March that there are plans for a new King Crimson studio album. Is there any update on this?

I don’t know anything about that (laughs). I never heard anything about that, so I have no update for you. I’m sorry. This happens when we try to predict the future in an interview. Maybe there is gonna be one, but I am trying not to say: “Here is what is gonna happen next year” because things change in rock.

How did Covid affect the making of “Liquid Tension Experiment 3” (2021) album?

Well, we came up with the bold idea to get together and write it and record it right during the lockdown. That summer (ed: 2020) nothing else was going on for me and six months after it and I was very reluctant to do that, as you can imagine. It was dangerous and it wasn’t safe to go out and stay in a hotel somewhere but we did that, as careful as you can be, to form what we call a “bubble” and not interact with other people. We were lucky in nobody got sick and it ended up really special and worthwhile that we got to make that album. Frankly, we would not have got to make that album if not for the lockdown because they would have been busy with Dream Theater and I would have been busy with King Crimson.

How much has your approach to bass changed over the years?

How much has your approach to bass changed over the years?

That’s a great question and it would probably take somebody else to analyze that. I don’t think about it. I don’t spend time analyzing my own playing, but I feel like a young player in that I am always trying to learn new things. Will I implement them? That’s a different story for someone else to evaluate. But I’m listening to other bass players and I’m trying new techniques and ideas and trying to break out of the same old playing, the way I used to, not because I don’t like what I used to do, but because that’s part of being a musician, being a bass player. That’s what I try to do. I’m not guaranteeing that I succeed in that, but from my brain looking out, that’s the way it is. A few years ago I was on tour with King Crimson but I was taking bass lessons online, it’s a thing called: “Scott’s Bass Lessons” and I signed up for the very basic one: “How to hold the bass – How to play a single note”. I found it pretty funny that before the show everybody was practicing the King Crimson music and I was in my own dressing room playing one note over and over again and looking at my finger and trying to be sure I have the right technique. So, even though I didn’t stick with that for the whole year, just for a few months, that’s an example of how I feel about my playing. I’m very happy to learn new techniques or to improve my old techniques.

How much different is the dynamics of the rhythm section between playing with Pat Mastelotto and Steve Gadd or Mike Portnoy or Manu Katché?

Completely different. Each drummer is very different. I don’t analyze and think: “Oh, how is this different?”, “what is what I am doing with this player?” I just play with them and try to lock in and make it really happen. With all those players you mentioned and all the players that I play with a lot, is very easy because we play together for years, we know each other’s playing and we can surprise each other, but it’s still a pleasant surprise. It’s not a thing: “Well, ok, I have to learn a new way to play”. So, it’s a really fun experience and it’s different each time and it’s different with each drummer, but it’s easy for us who play together a long time.

How difficult is it to remain calm in the studio when you work with people like John Lennon or Paul Simon?

I’m there for the music, so even if the person is famous or if they are unknown, in a way, it’s the same. I’m not much of a fan, even though I love a person’s music, I don’t act like a fan and I’m not motivated to act like a fan. So, John for instance, I met him and I was thrilled that I had the chance even to meet him, let alone to make music, but we are here to make music and I’m here to play the bass, so, my attitude and my feeling is the same when someone is very famous as it is for someone making their first album.

Me, as a fan, I would like some more about John Lennon. What was he like in the studio?

First of all, John didn’t choose me for the album (ed: “Double Fantasy” -1980), it was the producer, Jack Douglas (Aerosmith), whom I had worked with before. So, I came into the studio, I knew all the musicians, I didn’t know John, I didn’t know Yoko and his first words to me were: “They tell me you are good, just don’t play too many notes” and I smiled. He said that for two reasons: He was very New Yorker, in every sense, he lived in New York and he acted like a New Yorker. It was a kind of “in-your-face” way to say “hello”, which made me smile because I was a New Yorker then and I lived in New York and it’s an attitude that I’m used to. But also because I knew he didn’t know what kind of bass player I am, but I knew I wouldn’t play too many notes and there was nothing to worry about and I understood how he could be a little concerned. Somebody tells: “I’m a really good bass player”, it could be that I am gonna play too much and all over his music, so, he just dealt with it right away, the way he was, that he would deal with things right away. Ok, so, the sessions were fun, there was a lot of jamming in between; he loved to play Buddy Holly pieces, old pieces from the ‘50s and ‘60s and we were jamming and suddenly John would say: “Ok, let’s do it. Let’s do the song” and we were doing it in one or two takes. It didn’t take a long time to do his songs. He ‘d play me the song and it’s a John Lennon song and my thoughts were: “There are gonna be a thousand bass players who could do this very well and I’m so lucky that I’m the one who happens to be here. It could have been somebody different. I don’t even know for sure why it’s me”, but I was treasuring the experience of being there and there was that in the whole sessions. They made two albums (ed: also “Milk and Honey” -1984) out of it but it was only about two weeks that we were in the studio together.

What’s the story behind your amazing bass sound on Peter Gabriel’s “Don’t Give Up” (from “So” -1986)?

(Laughs) I will tell you that story because I remember it. In the beginning, I played with pick on the bass and we did it in England, at Peter’s studio which was attached to his big house he had at that time. It was the barn of the house and we were staying in the house for three or four weeks, a long time. I just had a child, my daughter, who was two months old and I didn’t want to leave her and her mother, so they came with me. So, what I had done was: I packed her diapers in my bass case, I put them everywhere in my bass case, I don’t know why I did that, because they certainly have diapers in England -they call them “nappies”, by the way- we call them “diapers” in America. For the second half of the piece, of “Don’t Give Up”, it goes to a different kind of groove, which we recorded separately and I looked around in the studio for some dampening material to put under the bass strings to make it bassier and more thumpy and have less sustain, it’s something that I do a lot. Most studios have some foam rubber line around or some kinds of rubber or even you could do it with cloth; I didn’t see anything but there were the diapers in the bass case, so I put one of my daughter’s diapers under the bass strings and that’s how I got the sound for the second half of the piece “Don’t Give Up”. She is 39 years old now and I love reminding her that story when she was only two months old, that she was a little part of that song.

Do you remember the Athens concert with Peter Gabriel in 1987, which released on DVD in 2013 as “Live in Athens 1987”?

Yes, this concert but also the video recording, because we stayed afterwards and did more repetitions, so they could get different film angles, of course. It was very special, it was one of my only times to Athens and we were there a long time setting afterwards, so I got to visit a little bit around Greece. It was really special.

Do you regret turning down the offer to tour with Pink Floyd in 1987 for “Momentary Lapse of Reason” album that you played on?

Thank you for doing your research on me. “Regret” is the wrong word. I would do the same again, but it’s unfortunate that I couldn’t do it. I would have loved to do it and this is the way with the freelance musicians and maybe freelance in any field: In a lucky year, you get called for good things that you can do them all. Some years, you are not so lucky and you either don’t get any calls or you get two calls for good things at the same time. So, in May of that year, I was recording with Pink Floyd and I was on a break from the Peter Gabriel tour that was continuing and David Gilmour asked me if I would like to tour with the band starting September, but Peter’s tour only ended at the end of September and I couldn’t do both and I would have liked to do both. If there was a month between, I would have done both, but my obligation and my heart, of course, was to stay with Peter and not leave. I could have asked him to leave before the end of his tour but that would just seem wrong to me. So, I chose to finish Peter’s tour and not do Pink Floyd’s. And a little story about what a great person David Gilmour is, of course, he understood that I wouldn’t do it and he got someone else, but at the end of that Pink Floyd tour over a year later, he called me and asked if I would like to come to the last concert, which was in New Jersey and help them celebrate the end of the tour and I thought: “How sweet that is of him, to even remember me; I am the guy who didn’t do the tour and he is taking his time out of the tour to think of calling me. So, he is a great guy”.

Why is there no competition among bass players? I mean, you, Nathan East, Leland Sklar, Billy Sheehan, you all love each other.

This happens because we are musicians. I don’t know any musicians who feel feelings that aren’t good about other players, especially good players who we admire each other, we learn from each other. I am talking now about bass players, I’m learning from those guys you mentioned and others and you know, I’m glad for their success. I think there are a lot of musicians on the planet Earth who are very good and some of us are luckier than others and get falling in good situations. For me, it was like meeting Peter Gabriel and Robert Fripp, it could have happened to somebody else instead of me, someone just as talented. So, I appreciate my luck and the talent of the bass players who are here and I try to learn from them. One thing about bass players: We rarely see each other, because it’s only one. Sometimes there are two drummers but mostly only one bass player in a band, so, we don’t see each other too much but those guys you mentioned are good guys and friends of mine. I don’t think it’s unique to bass; the drummers that I know have a community and they communicate all the time with each other and have a good relationship.

Ron Carter (Miles Davis Quintet -double bass) told me last year that the first take in the studio is always the best, because the first time you play the music, the second time you play yourself. Do you agree with this?

Ron Carter (Miles Davis Quintet -double bass) told me last year that the first take in the studio is always the best, because the first time you play the music, the second time you play yourself. Do you agree with this?

Well, that’s a great quote and I’m glad you remember it and I’m glad that you share it with me. I think it’s partly true. I talked about bass players, let me add that I admire Ron Carter, he’s at the top of that list and I’ve learned a great deal from him. Yeah, that’s wonderful. I’m in the rock field, not in jazz field and another factor to add on to that correct sentiment he has: I need to work at the pace and in the style that the artist is comfortable with. So, a jazz artist usually because of the budget they are gonna go and do the record in a day or two or three or four. A rock artist might take a month, so, if I’m in the studio with Peter Gabriel for one month to do 8 tracks, no, it’s not appropriate for me to say after the first take: “That’s it, I’m leaving”. I can tell the engineer: “That take I did is a very good one. Can you please mark it and put a star on it because it was very good?”. But through the years what I ‘ve learned to do is to adjust my pace of developing my part to the pace of the artist that is gonna work with. It’s just not gonna be right if I perfect my part to what’s happening on Monday, but everyone else’s part is different on Thursday, on the same piece, then I’d better be ready to come up with a more appropriate part on Thursday. So, I adjust to the time frame. I’m very happy when it’s quick, when it could be one take or two takes, I don’t mind, that’s the natural pace that I work at, but I’m used to working with artists, Paul Simon, for instance, who ‘d bring us in different times to play the same song. It would be different, the tempo would be different and I didn’t generally pick up with the bass part that I had from the other day.

Are there plans for a new album and tours by Stick Men?

Always tours. We just finished the tour. We will tour Europe next March and we ‘ve left open the fall. I hate to think so far ahead but fall 2025 I ‘m pretty sure we will do something but it depends a little bit on things like Peter Gabriel and Beat (laughs) and what time is left in the schedule. We lately don’t go in the studio but we trade files and try to add new material for each tour and when we come out with a recording of that new material, is really up to the other guys in the band, I don’t make those decisions. But there will be a new album from us, for sure, next year.

What did David Cross (King Crimson -violin) and Mel Collins add to the sound of Stick Men when they toured with you as guests?

It’s very special to have a guest for us. We tour a great deal by ourselves and we are fine with that, but they are a musical treat for us. Those guys, they are very different than each other the way they play, a lot more improvisation with Mel and with David we added “Starless” and the classic things that he has played on. So, it was a great treat for us with both of them and of course we enjoyed the chance to release the album of those live shows (ed: “Midori” with David Cross and “Roppongi” with Mel Collins) with them. I hope in the future Stick Men will have guests who ‘ll join us on tour. We ‘ve considered it in the last year, but we haven’t done lately, but we might do it on our next tour.

Do you have any names in your mind?

Do you have any names in your mind?

Not at all. No, we have no plans for it. It’s the kind of thing that can come up a month before the tour, we can do it or not, but there is a lot of latitude because there are a lot of players. We did a very short tour of Japan with Gary Husband (ed: Allan Holdsworth, John McLaughlin), which was very different. A great pianist and drummer, but we had him playing keyboard on the tour that it ended up right at the beginning of the Covid lockdown, so, we recorded that for a show and that’s the album that came out (ed: “Owari” -2020). But we ‘ve done it with a number of guests and usually we decide it about a month before the tour.

How much artistic freedom do you have on other people’s albums?

Very good question. It varies a great deal depending on who the artist is. Sometimes they want me completely to decide what I play, sometimes they want it to be a collaboration between us, which I’m very comfortable with and sometimes they have a pretty specific idea what they want me to play. I’m talking now, not about Peter Gabriel and Paul Simon, who we were going in the studio for a long time and work things out, but I do a lot of recording from here in my home studio where people send me files and we trade emails, but we don’t talk about it that much and sometimes they have a demo bass. Actually, I ask them if they have a bass idea to give me a demo bass file for me to listen and maybe incorporate some of that for my bass parts. So, I do care what the artist wants for the bass part because they wrote the piece and there is sensibility about this that is important, but also I’m most comfortable when I’m the one who is responsible for making the bass part that’s partly me and partly them.

Looking back, was the ‘80s a good decade for music?

Yes, it was of course and a lot of great stuff came out, but as you can tell from talking to me before, I’m not someone who focuses on the past, so, I never thought about what you said until just now when you said it. Yes, of course a lot of great music came out then.

Do you think because of the streaming services listening to an album from start to finish is becoming a kind of lost art?

Do you think because of the streaming services listening to an album from start to finish is becoming a kind of lost art?

I’m not in touch with how other people listen to music and for me, from my point of view, I don’t have the time to listen to other music that I wish I had. The fact of my very fortunate life as a freelance musician is that I’m almost always studying music that either I’m playing -in the case of Beat is, exactly, I’m playing soon- or I’m doing homework for something that’s coming up in a month or few weeks. Once in a while, I get the chance to listen to a track or two that I’m not working on or I am gonna work on, but usually most of my time is taken up with that music, that’s not a terrible problem, but I do wish I had more time to listen to new music by other people and sometimes I do, but not as much as most people I know.

Are you optimistic about the future of progressive music?

Sure, I know a lot of people who love it. The fanbase is there and that’s an important part of it and I think there are great musicians around the planet making amazing music in all genres, but particularly in progressive rock. I’m a fan of that style of music and there is a lot being done that is great. So, I can expect exciting surprising new music from that genre.

Was it a bit weird to record with Anderson Bruford Wakeman and Howe in 1989?

Not weird, I was honored to be asked to come in. To me, Yes without Chris Squire (bass) is not Yes, we all know that and I didn’t want to imitate or try to be Chris Squire. But it wasn’t weird; the guys wanted me and we made an album that was valid, it was very good. Then, we went on the road and I was going to play the Yes material, the Chris Squire’s parts. I involved myself with the difficult process of “how much do I play his parts exactly and how much do I put of myself into it?” and I encountered to the same situation when King Crimson started doing the classic bass parts of John Wetton. The decision of what’s important, what must be kept, but if I am on the road playing in a band, I want to be myself.

Did you like other bass players like Jack Bruce (Cream) or John Entwistle (The Who)?

Of course, both and I have a wonderful picture of me with Jack Bruce when I got to meet him. A fan, influenced by them both; like many bass players I was influenced by them both, yeah. I didn’t meet John Entwistle but great stuff he has done.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Tony Levin for his time. I should also thank Mr. Steve Karas for his valuable help.

Official Tony Levin website: https://tonylevin.com/

Official Tony Levin Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/tonylevinofficial/

Official Beat website: https://beat-tour.com/