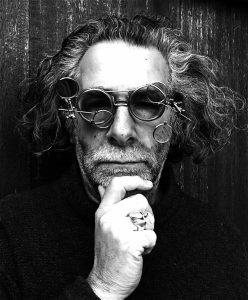

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: January 2018. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary musician: Kevin Godley. He is best known as the founding member, drummer, singer and songwriter of 10cc and Godley & Creme. He is also a very successful music video director working with The Beatles, Eric Clapton, The Police, U2 and many others. Currently, he has started a PledgeMusic campaign for his upcoming “Muscle Memory” album. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

How did you come up with the idea to ask fans to send you music for your upcoming “Muscle Memory” album?

How did you come up with the idea to ask fans to send you music for your upcoming “Muscle Memory” album?

A couple of years ago, two different people sent a couple of instrumental tracks to me and asked if I have been interested in writing songs over them, which I subsequently did and I enjoyed the experience very much. I have been considering making a solo album for a while, because the only instrument that I play is drums and it’s not the ideal instrument to write songs to. So, I thought that this experience was indicative of a possible way to make an album: to actually ask people to send me tracks that I would then sort through and put in my bag to work with. The response has been tremendous. I have over 50 tracks sent to me. Picking the ones that I wanna be working with, it’s gonna be tricky. I picked one already, I made a demo of it, I posted it actually on the “Muscle Memory” website. It’s exciting, it’s interesting, because I don’t know these people. All I am judging them on is what they send me. I am judging them on the piece of music, whether it inspires me or not. So far, it has been an inspirational situation.

Was it an interesting experience to make an ear movie, “Hog Fever” in 2016?

That was unusual because the music was secondary. It was the first time that I attempted to make music on my own. I was kind of bold about it, because the recording of the dialogue and the playing itself was going quite well, I decided to try and write some music to it. I found that I could, which was gratifying. So, it was an indication that that muscle does in fact still work, but that was a few years ago.

Why you decided to write your e-book autobiography, “Spacecake” (2015) as a screenplay?

That was my wife’s idea, actually. It wasn’t my idea at all. I was casting around for a style to write and to give me a starting point. When you start writing a book, you are facing a blank page, it’s a blank canvas. This gave me a focus, a way of not only getting people to say things, but getting me to have a conversation with myself. I find it the perfect device as a way in to what I do.

What’s the difference between you, KG and your alter ego KG(B)?

(Laughs) KG(B) is more of a cynic, I think. He tends to point out the negative or the possible negative sides and making KG look a bit foolish, over and over again.

Have you realized that you and Lol Creme are one of the best songwriting duos of all time?

Have you realized that you and Lol Creme are one of the best songwriting duos of all time?

Gosh, that’s very kind if you decided so. Thank you. It was a long partnership. We worked together in various mediums for over 27 years, since we were teenagers. We shared similar interests. We went to art college together, we grew up together. I suppose we developed a way of looking at the world together, which was the foundation of how we wrote songs, made films and videos. We had a particular attitude which probably comes across in all facets of our world.

“The Film of My Love” (“The Original Soundtrack” -1975) is my favourite 10cc song. Can you tell us a few words about this? I think it should have been covered by Scott Walker!

It’s my least favourite 10cc song -it really is- because it’s a kind of comedy song, it’s a philo- song. I can’t give you a constructive criticism about this song, because for me it sounds like what it was. It was: “Oh, we need one more song to complete the album”. We had this very silly idea about describing a love affair as a film. I don’t actually like the song at all. It’s a pretend song. It’s a pastiche song. I don’t think it had much value.

Did “Une Nuit a Paris” (“The Original Soundtrack” -1975) influence Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody”?

So, I am told. I don’t know how true that is. A lot of people have told me that. If it is true, that’s kind of flattering, but it was also an indictment to our record label that they didn’t have the balls to release “Une Nuit a Paris” as a single. Had they have done that, “Bohemian Rhapsody” may had some competition, and maybe we had stayed at the top of the charts for a number of weeks as well, who knows? But they were too scared.

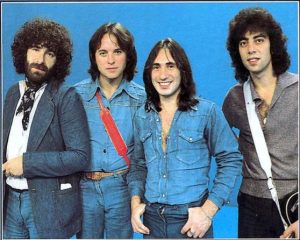

Why 10cc are not considered as cool and acceptable as Roxy Music or Talking Heads?

It’s purely because we never cultivated a cool image. All we had was the music. We never had a visual band image of any description whatsoever. We weren’t particularly good-looking, we didn’t dress in a particularly interesting way, we didn’t have a visual attitude to our music, which thinking back now, seems most peculiar as two of us, Lol Creme and myself, were art school graduates. We could apply ourselves to that area, but we never did. We were just four guys who made interesting music and I think had we ‘ve paid some attention to the visual side, maybe we would have more longevity and have been considered cooler. We also didn’t have any particularly bad habits, which were considered regular in those days: we didn’t take a lot of drugs, we didn’t fuck a lot of women, we didn’t get mad, we didn’t overdose, we didn’t do any crazy shit. We were relatively normal and responsible human beings, which it doesn’t really fit in an acceptable mode of a rock star, I suppose.

Are you satisfied with the BBC Four documentary “I’m Not in Love: The Story of 10cc” (2015)?

Are you satisfied with the BBC Four documentary “I’m Not in Love: The Story of 10cc” (2015)?

That was a good film. I thought it was a very balanced and intelligent documentary. I think it gave us our credibility back. Just to go back to your previous question, I think that the people who maybe considered us to be uncool, they hadn’t really looked into us too much and were not interested about too much and times did change. I think when that came out, we were looked at in a different light, which I thought was rather nice. I think people thought that we were pretty silly and pretty lightweight back in the day, but a reassessment of the band and the band’s art was long overdue and I think that redressed the balance.

Were you frustrated with the lack of commercial success that “Consequences” (1977) album by Godley & Creme had?

At the time, yes, obviously, because we were young. We thought at the time that anything we did would have some kind of commercial appeal, because we got well as 10cc. But we made a mistake of disappearing into the project for such a long time. I think it was between 14 and 18 months in the studio, which was a long time, not now, but then it was an extortionate amount of time. We didn’t keep an eye on what was going on in the real world. Things were changing. That kind of vanity project, if you like, wasn’t getting good press because pop and new wave was being polar opposite to what “Consequences” were about. When those kinds of changes happen, things are gonna roll over you, very-very quickly and when we emerged from the studio, that’s exactly what happened. It was almost as we made “Heaven’s Gate” (ed: 1980 film), the western. Regardless of how good or bad the film was, it was just a western. That’s what is happening. It was the same thing for concept albums unfortunately, and ours was the most conceptual, the biggest and overpriced of the lot, so it took a lot of the flak.

So, yeah there was a considerable amount of dismay and disappointment, but looking back it probably did us good. It taught us a lesson. As well as being an artist looking inward, you have to keep a wary eye on what’s going on, if you are interested in having some kind of commercial appeal. It gave us a shock. It took us back to our roots. Everything we did from that point on, was a lot simpler, a lot more considered, not necessarily a lot more focused, but certainly more considered. But also, strangely enough, at the time we were going to make music for film and consequently making film for music. There was one small piece of “Consequences” which was used for a cinema commercial for Benson & Hedges cigarettes, and we went into seeing film and music working together. That was part of the package that got us interested in making film for music. So, everything turned around. So, even though the project itself was a critical failure and a commercial failure, we learned a lot from doing it.

What’s the deeper meaning of number 17 on “Consequences” album?

There is not. It is just supposed to indicate that it does have a meaning (laughs). It was a number that Peter Cook conjured from nowhere, to give the impression that it means something, when in fact it doesn’t.

Can you describe to us the unusual recording process of Godley & Creme’s “Freeze Frame” (1979) album?

Can you describe to us the unusual recording process of Godley & Creme’s “Freeze Frame” (1979) album?

We were relatively open to different ways of working, but it was a very stripped down process. When we made “Consequences” we were in big posh 24-track studios, all the time. This was a local 16-track studio. So, we had to work quickly and more instinctively. When we tried stuff, we didn’t really make the “L” album like that, so creatively we realized that we can still do it. That gave us some confidence to begin the “Freeze Frame” album. So, there were no rules or specific processes we went through, other than once we started a track we finished it. One thing that we never ever did, was to record a series of 10 or 12 backing tracks. As most people do, we started a track and we finished it and then went to the next track. That’s how “Freeze Frame” was done.

I think probably the most successful song of “Freeze Frame” which unaccountably was a hit in Europe, was “An Englishman in New York”. That particular song gave us the opportunity to make our very first music video. I think that’s the interesting thing about this song. We didn’t actually direct it officially, but we were working with another director because the record label didn’t trust us to direct, and quite rightly so, we were given a director to work with. But we enjoyed the process so much, that we kind of took it over. We instinctively understood what was required and that was the ground zero in our video directing career. This is where all began.

How helpful was the fact that you, 10cc, had your own studio (Strawberry Studios) since the beginning?

I think it was very important but I also think it was equally important that is was outside London. We were away from the centre of the music business. So, there were too many of the influences coming in. We were kind of isolated, working in our little 10cc bubble of making things as we went along. I think had we have the same situation in London, things might have turned out slightly differently, but because we were way out, in the sticks, the sounds we were making, the songs we were writing were quite different to the work other people created. So, the two together I think, were significant assistance to what 10cc became, yeah.

What was it like to direct the music video for The Beatles song, “Real Love” (1996)?

Scary! To be given that responsibility by somebody who you know and admire and to carry that weight of shine probably the band that more than anybody helped you stay tuned in to your own dreams throughout our careers. Having to carry that weight was scary but also very flattering and a very exciting process. To see all that beautiful archive footage was just tremendous and also the footage of recording the new stuff together. It made everything very real for me. It was like “Ok, these guys who were gods to us when we were growing up going to art school, opened the door and let everybody else through”. They were our gods. But when I got to know them, they were just like us. They were just a bunch of tired guys who had the guts to go in and do something that they found inside their hearts, heads and souls and put it down on tape and wrote what they felt. They just happened to do it better than everybody else (laughs). To be given an opportunity to put all the stuff together in a meaningful way, was a dream come true.

Why you don’t like storytelling in music videos?

Why you don’t like storytelling in music videos?

Because it’s a good film rule. A music video is still a film. In a film you don’t see somebody walking down the street looking in shop windows, while he’s telling you he is walking down the street looking in shop windows, because you don’t need the same information twice. To me is the same thing with a music video. If somebody is dancing with a girl, taking her for a ride in the desert in the car, maybe you wanna see that, but you don’t want to hear it at the same time. It is doubling the information. It’s obvious that is what is going on. So, the pictures for me, in any music video, should either be something to do with performance or be giving you extra information, not doubling upon the information that already exists in audio.

Are you happy that the Gizmotron is available for sale again?

I am actually, because there were two problems with the original: The first was a failure of the materials used to build it. They were brittle, they were prone to temperature change, they were prone to moisture in the air and they weren’t particularly reliable. A Gizmotron took time to set up and when you got it to sound like an orchestra or a chainsaw, it was 50/50. Now, they made it using contemporary materials, they have taken a lot more time to do research and development and the finished thing is far more reliable. Back then also, when the thing came out, cheap synthesizer keyboards were also coming out with a far greater access to different sounds. If there was a choice between buy a Gizmotron and sounding like maybe an orchestra or maybe a chainsaw, or a synthesizer and sounding like 20 other instruments, people were gonna buy a synthesizer. So, we had two counts against us when it first came out. This time round, it’s more of a curio, it’s more of a specific device to do a specific job. I hope it will stand up.

Was it flattering that Jimmy Page used the Gizmotron on Led Zeppelin’s “In Through the Out Door” (1979) album?

Yes, I thought it was great. It was fantastic. They didn’t hear about it a great deal but there is a number of interesting people who used it over the years like Paul McCartney, Siouxsie and the Banshees… There is a list of them online, you should check it out. It gave a very specific sound, when it was working well. Once again, Jimmy Page used to use a violin bow on his guitar, anyway. So, it was probably a step forward from that.

Do you agree with the term “progressive rock” as far as the music of 10cc and Godley & Creme?

Do you agree with the term “progressive rock” as far as the music of 10cc and Godley & Creme?

“Progressive rock”, how do you mean? What is the difference? Let me be clear, you say that Godley & Creme is described as progressive rock or 10cc is described as progressive rock.

Yes.

Oh, progressive rock for me means something different or it used to mean. Progressive rock, as supposed when the term was originally coined, meant music that was pushing forwards, in some way, shape or form. Now, it’s more a derogatory phrase to suggest our music as interminable guitar solos, shoegazing… Like that (ed: its original meaning), yes. Today, I’m not so sure.

After the so-called punk rock revolution in 1977, if you were a good musician, it was a negative thing. I believe punk rock was a marketing invention.

It was an “anti-”. Everything was anti-music. Everything had to be reduced to its basics in order to be considered cool or acceptable. That actually didn’t last very long. I mean, you had a number of bands that were still pushing the boundary, even within their own limitations. Clash pushed the boundaries a little bit and then John Lydon moved ahead from The Sex Pistols and pushed his own boundaries. That “basics” thing was a marketing ploy. I don’t think that anybody really felt like that. There were people like Talking Heads who came along. Siouxsie and the Banshees came along. There were new responses to come out of that movement that made some incredible records. I wouldn’t use the word “progressive”, but they were challenging records. I don’t think that has really stopped. I think that moment in time you are talking about was quite brief. Everything had to be crude, everything had to be three chords. That didn’t actually last that long because it ran out of steam pretty quickly.

Your old friend, Andy Summers (The Police –guitar) told me last August that punk rock hasn’t much to do with music.

It wasn’t. I think The Police were a great example of moving ahead. They kind of fitted to punk rock but they used it as a starting point. They were a punk band, to start up with, until they found themselves, maybe an album or two in. And then, they were huge. As well as looking good and performing well, they made good music.

Do you think social media like Youtube and Facebook have helped younger listeners to learn about the music of 10cc?

Do you think social media like Youtube and Facebook have helped younger listeners to learn about the music of 10cc?

Frankly, I have no idea. It’s more accessible, maybe not so much on Youtube because the stuff on Youtube obviously is very old and looks very dated, but the access is I suppose the good thing. One of the things about Youtube to me is like an encyclopedia on film. Anything you wanna know about anything, there is every film clip on there, of anything. So, if you wanna know about us, that’s the place to start, I guess and you can research us there. The one other amazing thing that the Internet has achieved and Youtube has helped to achieve, is a lot people to become musical archeologists. They just don’t classify by what other people say about them. The whole notion of 10cc being “uncool” was just a myth passed on through the generations. Now, if you incline to do so, you can actually go online and check us out: Check out how we sounded, what we looked like, how we played, have a listen, have a look and make your own mind up. You can dig deep. I suppose the answer is yes. Some social media like Youtube and Wikipedia, are more information sites than anything and it certainly has been a huge assistance to the “Muscle Memory” project, which wouldn’t be possible without the Internet and associated technologies.

Why you don’t consider yourself a performer?

It’s what I said: I don’t consider myself a performer, I suppose because I don’t look particularly like a performer. I don’t enjoy being on a stage particularly, unless I am in the back playing the drums. Let’s just say I am not a particularly confident performer or a particularly confident frontman.

Do you have any musical ambitions left?

I do, I have many ambitions left, it’s all different, in all the areas I work with and I am constantly creating opportunities to bring them to life. Making the “Muscle Memory” album, if I get to do it, it will be one ambition. I would also like to do a musical film, but also I love orchestra and I would like to work with it, in a more intimate way. There are a couple of album ideas, although perhaps the word “album” is a little dated these days. There are a few musical ideas that I would like to explore, which it wouldn’t necessarily be me as an artist doing them. I think if you are a musician, you don’t just switch it off and do something else. There is always an element of sound or music in everything that I do. So, we can say that I have lots of audio ambitions left to fulfill.

You are always doing great interviews. Is there any question that you would like to answer but nobody ever asked you?

(Laughs) I think that was it! You just asked it. No one ever asked me if there is a question I wanted to be asked before. That’s a very difficult question. Most interviewers cover everything. No one ever asked be why I do what I do. They always ask me how I do it, when I do it, what I do -describing the process- but nobody ever as far as I can recall, asked me why I do it.

Have you ever listened to “Kew.Rhone” (1977) album by John Greaves (Henry Cow) and Peter Blegvad (Slapp Happy)? It is a very avant-garde album.

Have you ever listened to “Kew.Rhone” (1977) album by John Greaves (Henry Cow) and Peter Blegvad (Slapp Happy)? It is a very avant-garde album.

I don’t listen to a lot of avant-garde music. I have a relatively conservative taste. I occasionally listen to Stockhausen, John Cage, Scott Walker and so on, but it’s more to appreciate them than to enjoy them. I listen to a lot of avant-garde jazz, but I have a relatively catholic taste, although I occasionally listen to a lot of Benjamin Clementine. He’s pretty interesting and unlike anybody else that I’ve heard. He just sounds so free and spontaneous, yet haunting at the same time. I despair every time I watch music television, it plays yet another group with drums, bass, guitar, vocals, keyboards. The only TV show that actually features anything new, is Jools Holland’s show. That’s a great show. There is always something radical and that’s great. It’s difficult to find stuff these days because there is so much out there. So much of it sounds the same.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr Kevin Godley for his time and to Billy James for his valuable help.

Official Kevin Godley website: http://www.kevin-godley.com

“Muscle Memory” PledgeMusic campaign page: https://www.pledgemusic.com/projects/kevin-godley-muscle-memory