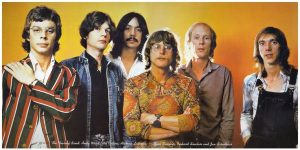

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: December 2025. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary keyboard player: Dave Sinclair. He is most well-known as a founding member of Caravan, one the most important bands of the Canterbury Scene, releasing with them classic albums as “In the Land of Grey and Pink” (1971) and “For Girls Who Grow Plump In the Night” (1973). He has also been a member of The Wilde Flowers, Matching Mole, Camel, Hatfield and the North and The Polite Force. In addition, he has released several albums as a solo artist. In 2025 he released the albums “Tears in His Eyes” and “Homemade Jams” (the latter with John Murphy on guitar -recorded in 1973-‘74) via his Bandcamp page https://davesinclair.bandcamp.com . Read below the very interesting things he told us:

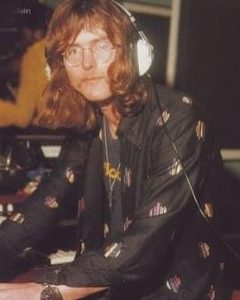

In 2025, I released a new album on Bandcamp titled “Tears in His Eyes”. The title comes from my song “The Piano Player”, with lyrics by John Murphy. This new version with my vocals opens the album. The song was originally recorded for my “Moon Over Man” solo album in 1976-77. I am now also hoping to re-release those analogue recordings on a new vinyl album for the 50th anniversary edition. The song assumes that I am the piano player, and in recent years it has taken on a deeper meaning for me. After suffering a stroke at the beginning of 2023, I lost the use of my right hand for playing and soloing -about the worst thing that can happen to a keyboard player. Incidentally, I had often wondered how much of my music had actually been heard, as I am not really a “social-media” type and am no longer part of a well-known band.

Fortunately, with rehabilitation I have now regained much of my normal mobility and continue to make progress. Most of the material on “Tears in His Eyes” had previously been unreleased or unfinished, and a couple of tracks also feature different vocalists. In addition, I released another Bandcamp album in 2025 titled “Homemade Jams”. This material, dating from 1973-‘74, was recorded on various reel-to-reel tape machines without vocals. The tapes were digitally restored by my son Nick after many weeks of hard work -something I was unable to do myself. These recordings consist of a series of private jam sessions with musician friends following my departure from Caravan and Matching Mole, and had not been heard by anyone for over 50 years.

How did you come up with the idea to make a series of Youtube videos titled “Dave Sinclair… The Lost Interview” in 2022?

Ah yes, this was my son Nick’s idea. He felt that much of what I had said in interviews had been conveniently edited out to make a more simple or shortened version. So, using the recordings I had already made, he set about presenting the answers in a more detailed and accurate way, which eventually led to the idea for the “Dave Sinclair… The Lost Interview” video series.

Would you like to tell us a few words about your solo album “Hook, Line & Sinclair” (2021)?

After recording many albums at Mothership Studio in Kyoto City I eventually moved to Yuge Island in the Kamijima group of islands in the Inland Sea of Japan. Lucky to get a seafront position on the Island, I found myself surrounded by a shipping and seafaring community. In fact, after my first initial visit to the Island a few months before moving there, I was greatly inspired to write a song. The song title became “Island of Dreams”. I realised after moving there that my lyrics really rang true. The song is now very popular among the people from the Kamijima Islands. I sang the English version and Yammy sang the Japanese. Moving there gave me the inspiration to make a simpler album, more in keeping with the natural environment and lack of immediate funding. Although I recorded mainly at home, I did return on occasions to Mothership Studio in Kyoto for editing and mastering. I felt the help and support of the local people on Yuge Island gave me a lot of encouragement.

I had always wanted to visit Japan and felt a strong affinity with the country. I finally got the chance in January 1979 while on a worldwide Camel tour. My first sight of Japan was Mount Fuji, seen from the airplane after an 18-hour journey from London via Alaska. I returned more than 20 years later to play concerts with Caravan in 2002. After leaving Caravan, I recorded my “Full Circle” and “Into the Sun” albums in 2003, which unfortunately resulted in substantial debts and ultimately led to the collapse of my piano business and my marriage. With considerable support from people I knew in Japan, I felt that my best chance of surviving within the musical world was to move there, which I did in 2005.

What’s the story behind the song “For Richard” from Caravan’s “If I Could Do It All Over Again, I Could Do It All Over You” (1970)?

Richard Sinclair, our bass player, kept playing a rhythmic sequence based around four notes, but he wasn’t satisfied with where it was heading. I suggested that I would try developing it further. I initially wrote a backing part, which inspired me to continue working on the piece. This eventually became a longer composition that the whole band came together on, and I titled it “For Richard” for obvious reasons. Since then, the track has appeared in many different recordings across various Caravan albums and still is an important part of the Caravan set list.

Are you proud that Caravan’s “In the Land of Grey and Pink” (1971) is considered a classic album?

Yes, certainly. It’s remarkable that the album is still in production and selling some 55 years later. It was also especially rewarding for me at the time, as I had a major involvement in the album — not only in the writing and playing, but also in the arranging.

Please tell us everything we should know about your incredible performance in “Nine Feet Underground” (from “In the Land of Grey and Pink”).

When I moved into my flat nine feet underground, I finally felt free from outside interference. I could play without disturbing anyone, and without being disturbed myself. This allowed me to take my time piecing together the various sections of the “Nine Feet Underground.” track. These were musical ideas, songs, and riffs that I particularly enjoyed soloing over. Putting them together in the right sequence to create a coherent and meaningful piece became very important to me, especially once I realised that the band was interested in developing longer compositions along the lines of “For Richard”. When I felt the piece was nearly finished, I took it to my local music club and asked some friends to listen while I played it on the piano. Their reaction was so positive that I felt confident offering it to the band, hoping they would agree to record it in the studio. Fortunately, we also had David Hitchcock as producer, and I believe it was largely due to him that the piece was recorded and produced so successfully. A month or two after the album’s release, I heard “Nine Feet Underground” being played very loudly at a local club. Listening to it then, I felt like a fan of the band – and I really enjoyed it.

Festival sites are always very different from regular live gigs. With so many people, bands, and an assortment of equipment and personnel, it’s remarkable that everything comes together at all – and without road crews it would be impossible. I had a brief opportunity to speak with Frank Zappa before the performance. He didn’t say very much and came across as very cool, perhaps eager to get on stage and play. In the end, the jam worked out well, although the sound could have been better. Frank was keen to play with most of the bands appearing that day, as he was unable to perform with his own band at the festival.

How helpful was the period you played in Wilde Flowers to your later career?

I learned a great deal during those early days, but what stands out most when I look back is the sheer enjoyment of it all. The Tamla (ed: Motown) and soul music which we used to play really drove things forward, with everyone dancing and having a good time. At the time, I couldn’t imagine people sitting quietly in chairs, or just standing listening to music – though, of course, that’s exactly what happened as performances evolved in later years.

Was it an interesting experience to perform with Caravan on TV shows like Colour Me Pop, Top of the Pops and Beat Club?

Yes, it was certainly interesting, though very different from playing live concerts. Some television shows were pre-recorded with only the vocals performed live, while others required us to mime completely, which we found quite disconcerting and somewhat sterile. I remember one occasion when, after recording a show, we all swapped instruments and -with a serious helping of alcohol- delivered what we believed was a spectacular performance. I’ve never seen it since, and it’s probably just as well. Beat Club, recorded in Bremen, was broadcast to around 50 million viewers, and I have very fond memories of appearing on that programme many times.

Did you enjoy the Caravan reunion in 1990?

Yes, very much so. Apparently, we had the largest audience of all the shows, or so I was told. The stage itself was incredibly hot, surrounded with an astonishing number of lighting rigs. When the bank of lights behind me came on, it felt like being thrust into Death Valley -thousands of watts of heat hitting my back at once. Despite the extreme temperatures, it turned out to be a very worthwhile reunion and effectively re-started our touring days. We were also joined on stage by the wonderful Jimmy Hastings, Pye’s (guitar, vocals) brother, on sax and flute, which made it even more special. So yes, it was a very enjoyable experience.

I had always admired Robert’s drumming, having listened to Soft Machine and having briefly played with him at an earlier Caravan gig where we performed some of Hugh Hopper’s (ed: Soft Machine -bass) songs. In October 1971, three months after leaving Caravan, I was unexpectedly contacted by Robert while I was in Portugal. He sent me a telegram that read: “Come back, your country needs you”. After returning to England and getting in touch, Robert came down to my place in Kent and was keen to hear the songs I had been composing and playing on the piano. He selected one and asked if it would be all right to change the lyrics and record it. That’s how “O Caroline” came about. At the time, I felt that this was exactly the kind of music Robert was interested in pursuing.

After recording the main song parts for “O Caroline,” the band headed off for the evening, but Robert stayed behind. When we returned the next morning, he was still there and said: “Have a listen”. He had worked on the track throughout the night – a truly special moment for everyone. Later in the studio the recording conditions were far from ideal. It was winter, and we had only a single electric three-bar heater, which we crowded around until our fingers were warm enough for another take. I also found myself holding back musically, not wanting to overplay, which is where Dave MacRae’s (ed: electric piano) contribution became invaluable after he joined us. Although we went on to play many gigs in the UK and abroad, I eventually felt a little uncomfortable with the material, having initially imagined the music might be more song-oriented. Nevertheless, it was a very valuable experience, and Dave MacRae proved to be an excellent addition to the band.

Why did you decide to leave Matching Mole after their first album?

This is largely answered in the previous question. While the experience was valuable, I gradually felt that the musical direction wasn’t quite what I had originally envisaged, particularly in terms of being more song-based. That ultimately led me to move on.

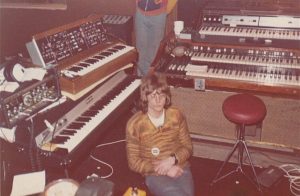

I first became interested in the piano at a very early age, when my parents bought one for my elder brother to take lessons on. At the time, I don’t think my parents were aware that we had a famous ancestor from the 17th century: John Blow (Blow is my mother’s maiden name), who was composer to five English monarchs and organist at both St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, where he was buried in 1708 in the musician’s gallery. I used to creep downstairs late at night and quietly compose little pieces on the piano with the soft pedal engaged, until my parents, disturbed by the sound, would bang on the floor above — sending me scuttling back to bed. The piano remained my main instrument and probably influenced my later decision to restore and sell pianos professionally. When I joined the Canterbury group The Wilde Flowers, I initially played bass guitar but soon switched to a Vox Continental organ. As we began writing more of our own material, it became clear that a fuller sound was needed, which is when the Hammond A100 entered the picture. The band then evolved into Caravan. With Caravan, I spent a great deal of time developing my Hammond sound.

I didn’t want it merely as a backing instrument that gave extra impetus to the group as a whole; I wanted it to express deeper emotion, often using single-note solos and various effects pedals to make it feel almost like a human voice -though the results weren’t always successful. As keyboard technology advanced and instruments became lighter and more complex, I was persuaded to simplify my setup. Eventually, I found myself using electronic keyboards that didn’t inspire me in the same way. On some foreign tours, I was even presented with unfamiliar instruments -not the ones I had asked for, and lengthy manuals — sometimes I didn’t even know where the on/off switch was. Happily, in recent times my son Nick spent over a year restoring my Hammond A100. When I recently played it again in the UK, it sounded exactly as it had some 55 years ago. I was amazed. It really inspired me to reuse the Hammond once more. With the further addition of a fuzz box, wah-wah pedal, and Copicat echo, recently installed, I’m sure it won’t be long before I’m recording with it again.

What do you remember the most of the period you played with Camel?

Andy Latimer kept a tight control over the music and performances, but the band certainly knew how to enjoy themselves during their free time. I was 30 years old when I joined Camel, and I vividly remember my first concert with them after many days of preparation and rehearsals in a large theatre. I was extremely nervous and had the distinct feeling that I was far too old to be there, which is amusing to look back on now, 47 years later. That feeling soon faded, and I settled into the routine of long tours across the UK and abroad. Although I had less freedom to expand my playing than I did in Caravan, I still enjoyed working with such exceptional musicians. However, playing the same set night after night -around 70 concerts in Europe alone- it eventually took its toll. After completing the Japanese and US tour, I returned to the UK and took a job as a London courier driver, which brought me back down to earth, so to speak.

The Hammond A100 was originally intended as a living-room instrument, yet I successfully toured with it for many years as did Georgie Fame. It was very reassuring to have Billy Dunn looking after it -he was the Hammond expert in the UK, maintaining many Hammonds including Keith Emerson’s instruments. The A100 was similar to the B3 and featured a full console rather than a spinet design, allowing for a much deeper and richer sound through its extensive drawbar system.

Who are your influences on keyboards?

After hearing the Hammond organ on recordings by bands such as The Nice and Procol Harum, I went to the Marquee Club to see The Nice perform live. Seeing Keith Emerson, and later Brian Auger with The Trinity and Julie Driscoll at Alexandra Palace in 1967, completely convinced me that I had to own a Hammond organ-despite it costing over £1,000 at the time (1967).

What inspired to start using Mellotron?

I first used a Mellotron during the recording of Caravan’s “Grey and Pink” album at Decca Studios. It happened to be available in the studio, and I was looking for a different sound, so I experimented with it and incorporated it into the recordings.

Is it flattering that you have influenced great keyboard players such as Geoff Downes (Yes, Asia, The Buggles)?

I never learned to play the keyboard in a formal way. I can’t read music and I couldn’t manage hours of finger exercises allowing me to do it, although I know it would have been useful. I simply let sounds enter my head and allowed my fingers to translate those feelings. Sometimes it worked well, and other times less so. But if others have found enjoyment or inspiration in my playing, that’s extremely gratifying and very inspiring for me.

Did you like other keyboard players from your era like Mike Ratledge (Soft Machine) and Dave Stewart (Egg, National Health, Hatfield and the North)?

Did you like other keyboard players from your era like Mike Ratledge (Soft Machine) and Dave Stewart (Egg, National Health, Hatfield and the North)?

Yes, very much so. I became a fan of Dave Stewart after seeing him play with Egg at Canterbury University. Mike Ratledge was another amazing player, with a deep understanding of jazz. In fact, during Soft Machine’s break from touring the US with Jimi Hendrix, Mike showed me some interesting jazz chords at my home in Whitstable. Of course, I also greatly enjoyed listening to and watching Keith Emerson and Brian Auger among others -all of them were hugely influential musicians of that era.

In your opinion, what made the Canterbury Scene so unique?

Mike Ratledge, Dave Stewart, and I all became prominent keyboard players within our respective bands, which at the time was slightly unusual in rock music, where the guitar was normally the dominant instrument. Of course, keyboard players were common in jazz, but not so much in rock bands. But with the so-called “Canterbury Scene,” it really depends on what people mean by that term. If it refers to the core group of bands active between roughly 1965 and 1971, then it makes sense. After that, the label seemed to be applied rather loosely, with many bands either being placed into the category or adopting it themselves simply because of some connection -however small- to Canterbury or to musicians from the area. In many ways, it resembled the late-1960s San Francisco scene, where friends played in each other’s bands in various configurations. At the time, there was also a noticeable absence of “London influence” in and around the Canterbury Cathedral City -something that is no longer the case today. But Caravan were quite unique in the sense of not really fitting into any one particular category, be it rock, jazz, classical, blues, etc. There seemed to be a combination of many styles. Maybe that’s why some people applied the “Canterbury” tag?

Are you happy with your participation in the documentary “Romantic Warriors III: Canterbury Tales” (2015) ?

I actually curtailed my planned honeymoon in Venice and rushed back to London in order to take part in the recording. It was all rather hectic, with many unexpected events along the way. I would have liked to have had more time, but in the end, I think everything came together satisfactorily.

How important is improvisation to you?

Without improvisation, I have far less interest in playing music, even though structured arrangements are clearly important within a band context. Improvisation opens the door to endless possibilities and discoveries, and for me it remains an essential part of musical expression.

Who is the person you had the best musical chemistry with onstage?

I had good on-stage chemistry with Robert Wyatt, Doug Boyle (ed: Caravan, Robert Plant –guitar), Jimmy Hastings, and Andy Ward (ed: drums) from Camel. At times, I also felt a strong musical connection with Caravan’s drummer, Richard Coughlan.

Would you like to tell us a few words about Jimmy Hastings (Caravan -saxophone, flute) who passed in March 2024?

Jimmy Hastings’ musical ability, shaped by both natural talent and hard work, was further enhanced by the many outstanding musicians he played with throughout his life. I was deeply honoured when he agreed to travel all the way to Japan to tour with me. I remember many wonderful moments with Jimmy -not only his brilliant musicianship, but also his warm, friendly, and truly gentlemanly manner. He is very sadly missed.

Do you think because of the streaming services listening to an album from start to finish is becoming a kind of lost art?

If songs or pieces are relatively short, then selecting individual tracks can make sense. However, in the case of longer works — especially those forming part of a concept album — it is often in the listener’s best interest to experience the album as a whole. In those situations, I believe purchasing and listening to the complete album remains the most rewarding approach.

Yes, very much so. I more or less grew up with the Beatles, although they were a few years older than me. I always eagerly anticipated each new single, expecting it to be something special. I clearly remember dancing to their early releases at an outdoor campsite when I visited Spain in 1963 -their music seemed to be playing everywhere at the time. It was quite amazing, and so it progressed from there on.

Are you optimistic about the future of progressive music?

I believe there will always be musicians who want to go beyond what is expected of them, and who are willing to indulge their own creative instincts in ways that appeal to them personally. People are very different, and there will always be listeners who appreciate particular musical approaches. That said, I think one of the most important aspects of live music, generally speaking, is rhythm, (and of course entertainment) — it’s the most natural and immediately appealing element. Some fans of progressive music also seem to enjoy the complexity of unusual rhythms and nuances, precisely because they don’t fully understand them. That challenge can be part of the attraction. Just my opinion, “God Only Knows”!

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Dave Sinclair for his time.

Official Dave Sinclair website: https://www.dsincs-music.com

Official Dave Sinclair Bandcamp page: https://davesinclair.bandcamp.com